Patel is an Indian surname or title, predominantly found in the state of Gujarat, representing the community of land-owning farmers and later businessmen, agriculturalists and merchants. Traditionally the title is a status name referring to the village chieftains during medieval times, and was later retained as successive generations stemmed out into communities of landowners. There are roughly 500,000 Patels outside India, including about 150,000 in the United Kingdom and about 150,000 in the United States. Nearly 1 in 10 people of Indian origin in the US is a Patel.

Bhil or Bheel is an ethnic group in western India. They speak the Bhil languages, a subgroup of the Western Zone of the Indo-Aryan languages. Bhils are members of a tribal group outside the fold of Hinduism and the caste system.

Parmar, also known as Panwar or Pawar, is a Rajput clan found in Northern and Central India, especially in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Punjab, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and North Maharashtra. The clan name is also used by Kōḷīs, Garoḍās, Līmaciyā Valands, Mōcīs, Tūrīs, Luhārs, Kansārās, Darajīs, Bhāvasārs, Cūnvāḷiyās, Ghañcīs, Harijans, Sōnīs, Sutārs, Dhobīs, Khavāsas, Rabārīs, Āhīrs, Sandhīs, Pīñjārās, Vāñjhās, Dhūḷadhōyās, Rāvaḷs, Vāgharīs, Bhīls, Āñjaṇās, Mer and Ḍhēḍhs.

The Dhangars are a herding caste of people found in the Indian states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Goa, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. They are referred as Gavli in southern Maharashtra, Goa and northern Karnataka, Golla in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka and Ahir in northern Maharashtra. Some Gavlis live in forested hill tracts of India's Western Ghats. Gavli, also known as Dange or Mhaske, and Ahir are a sub-caste of Dhangar. However, there are many distinct Gavli castes in Maharashtra and Dhangar Gavli is one of them.

Solanki also known as Chaulukya is a clan name originally associated with the Rajputs in Northern India but which has also been borrowed by other communities such as the Saharias as a means of advancement by the process of sanskritisation. Other groups that use the name include the Bhils of Rajasthan, Koḷis, Ghān̄cīs, Kumbhārs, Bāroṭs, Kaḍiyās, Darjīs, Mocīs, Ḍheḍhs, and Bhangīs.

Patidar, formerly known as Kanbi, is an Indian land-owning and peasant caste and community native to Gujarat. The community comprises at multiple subcastes, most prominently the Levas and Kadvas. They form one of the dominant castes in Gujarat. The title of Patidar originally conferred to the land owning aristocratic class of Gujarati Kanbis; however, it was later applied en masse to the entirety of the Kanbi population who lay claim to a land owning identity, partly as a result of land reforms during the British Raj.

The Gurjar are an Indo-Aryan agricultural ethnic community, residing mainly in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, divided internally into various clan groups. They were traditionally involved in agriculture, pastoral and nomadic activities and formed a large heterogeneous group. The historical role of Gurjars has been quite diverse in society: at one end they have been founders of several kingdoms and dynasties and, at the other end, some are still nomads with no land of their own.

The Anjana Chaudhari is a caste in the Indian state of Gujarat. The Anjana Chaudharis are farmer by profession, most of them are small cultivators. Anjana Chaudharis of Gujarat also known as Anjana Patel in their area.

The Malhar also known as Panbhare is a subcaste of the Koli caste found in the Indian states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa and Karnataka. The Malhar Kolis used to work as Yeskar and they were subedar or fortkeeper of Sinhagad, Torna and Rajgad forts during time of Shivaji. Their local traditional dance is Tarpa dance in Maharashtra and they worship the Waghowa Devi, a lion goddess.

Chhipi is a caste of people with ancestral roots tracing back to India. These people are basically Rajputs and used to wear Kshatriya attire. These people were skilled in the art of war, Later people of this caste started doing printing work. They are found in the states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh of India.

The Tadvi Bhil is a tribal community found in the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan in India. They are from the larger Bhil ethnic group, and are a clan of it. They use the surname Tadvi or sometimes the name of their Kul or Gan; the Dhankas of Gujarat and Maharashtra use Tadvi or Tetariya.

The Rathva or Rathwa also spelled as Rathava and Rathawa is a Subcaste of the Koli caste found in the Indian state of Gujarat. Rathava Kolis were agriculturist by profession and turbulent by habits but now lives like Adivasis such as Bhil because of their neighborhood

The Koli is also known as Koliya in ancient India. Mahawar also known as Mahor and spelled as Mahaur, Mahour and Mahavar is a sub-caste of the Koli caste in the Indian states of Rajasthan, Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Mahawar kolis Inter-marry with Shakya kolis but not with any other subcaste of Kolis. The Mahawar kolis along with other Koli subcastes Shakyawar, Jaiswar, Kabirpanthi and Shankhwar kolis of Uttar Pradesh tried to uplift the social status in Hindu society by supporting the 'All India Kshatriya Koli Mahasabha' leaders of Ajmer.

Gavli, Gawli or Gavali is a Hindu caste found in the Indian states of Maharashtra and Madhya pradesh. They a part of the Yadav community.

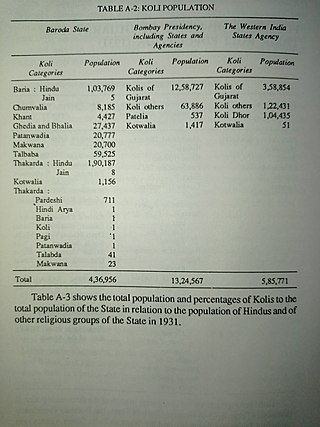

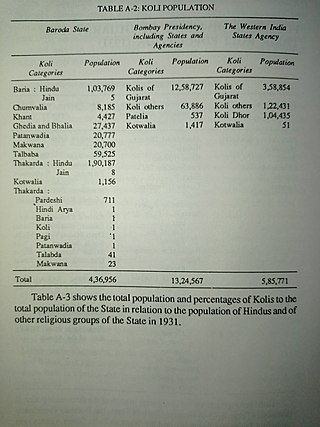

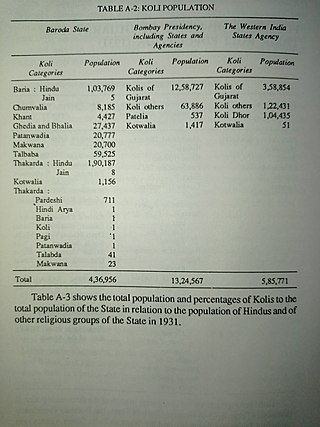

Baria, or Baraiya,Bareeya and Bariya is a clan (Gotra) of the Koli caste found in the Indian State of Gujarat and Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu. the Devgad Baria was their Stronghold or given their name to Baria State in Gujarat. according to the historian Y.V.S Nath, the ruling royal family of Baria State is original Koli by caste but later they claimed to be of Rajput origin to be in high status among other Princely States.

KHAM stands for Koli Kshatriya, Harijan, Adivasi and Muslim. Here Kshatriya is taken to include the Kolis. In the KHAM combine, Kolis were the largest caste represented at different levels of politics, and Madhavsinh Solanki increased the reservation quota for Other Backward Classes in Gujarat. The theory was propounded by Madhavsinh Solanki in 1980s in Gujarat to create vote bank for Indian National Congress and prepared by Jhinabhai Darji. Using the formula, Congress was able to capture 149 seats in the 182-member Assembly. However the formula alienated Patels permanently from Congress. during the Kham alliance, castes such as Bania, Patidar and Brahmins lost their importance in the state, so they propounded the Anti reservation agitation in 1981 and 1985 in Gujarat to get rid of the power of OBC castes.

Modern historians agree that Rajputs consisted of a mix of various different social groups and different varnas. Rajputisation explains the process by which such diverse communities coalesced into the Rajput community.

Natvarsinhji Kesarsinhji Solanki was a politician from the Gujarat state of India. He founded the Charotar Kshatriya Samaj and the Gujarat Kshatriya Sabha. He was elected to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Parliament of India.

The Chunvalia, or Chuvalia, Chunwalia is a subcaste of the Koli caste, found in the Indian state of Gujarat. The Chunvalia Kolis were the first Indian caste to adopt the game of cricket in India. Chunvalia Kolis were classified as a Criminal Tribe under Criminal Tribes Act by government of the British Raj because of their purported anti-social behaviour and activities, such as alleged dacoity in Gujarat. During the First World War, Chunwalia Kolis were enlisted as soldiers in British Indian Army by the Bombay government of British India.

The Talapada, or Talpada, is a subcaste of the Koli caste of Gujarat state in India. Talapada Kolis are agriculturists by profession. they were members of the Gujarat Kshatriya Sabha, an organisation launched by Natwarsinh Solanki who was a Koli elite. In 1907, they were classified by the British as a Criminal Tribe, ascribing to them a range of anti-social activities such as highway robbery, murder, and theft of animals, cattle and standing crops. They were also alleged to be blackmailers and hired assassins.