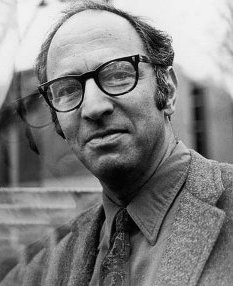

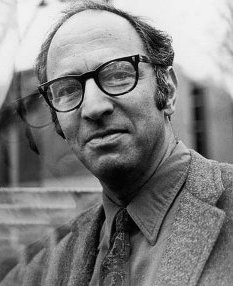

Falsifiability is a deductive standard of evaluation of scientific theories and hypotheses, introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in his book The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934). A theory or hypothesis is falsifiable if it can be logically contradicted by an empirical test.

Sir Karl Raimund Popper was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the classical inductivist views on the scientific method in favour of empirical falsification. According to Popper, a theory in the empirical sciences can never be proven, but it can be falsified, meaning that it can be scrutinised with decisive experiments. Popper was opposed to the classical justificationist account of knowledge, which he replaced with critical rationalism, namely "the first non-justificational philosophy of criticism in the history of philosophy".

Logical positivism, later called logical empiricism, and both of which together are also known as neopositivism, is a movement whose central thesis is the verification principle. This theory of knowledge asserted that only statements verifiable through direct observation or logical proof are meaningful in terms of conveying truth value, information or factual content. Starting in the late 1920s, groups of philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians formed the Berlin Circle and the Vienna Circle, which, in these two cities, would propound the ideas of logical positivism.

A paradigm shift is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. It is a concept in the philosophy of science that was introduced and brought into the common lexicon by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn. Even though Kuhn restricted the use of the term to the natural sciences, the concept of a paradigm shift has also been used in numerous non-scientific contexts to describe a profound change in a fundamental model or perception of events.

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultimate purpose of science. This discipline overlaps with metaphysics, ontology, and epistemology, for example, when it explores the relationship between science and truth. Philosophy of science focuses on metaphysical, epistemic and semantic aspects of science. Ethical issues such as bioethics and scientific misconduct are often considered ethics or science studies rather than the philosophy of science.

First formulated by David Hume, the problem of induction questions our reasons for believing that the future will resemble the past, or more broadly it questions predictions about unobserved things based on previous observations. This inference from the observed to the unobserved is known as "inductive inferences", and Hume, while acknowledging that everyone does and must make such inferences, argued that there is no non-circular way to justify them, thereby undermining one of the Enlightenment pillars of rationality.

Scientific evidence is evidence that serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis, although scientists also use evidence in other ways, such as when applying theories to practical problems. Such evidence is expected to be empirical evidence and interpretable in accordance with the scientific method. Standards for scientific evidence vary according to the field of inquiry, but the strength of scientific evidence is generally based on the results of statistical analysis and the strength of scientific controls.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a book about the history of science by philosopher Thomas S. Kuhn. Its publication was a landmark event in the history, philosophy, and sociology of science. Kuhn challenged the then prevailing view of progress in science in which scientific progress was viewed as "development-by-accumulation" of accepted facts and theories. Kuhn argued for an episodic model in which periods of conceptual continuity where there is cumulative progress, which Kuhn referred to as periods of "normal science", were interrupted by periods of revolutionary science. The discovery of "anomalies" during revolutions in science leads to new paradigms. New paradigms then ask new questions of old data, move beyond the mere "puzzle-solving" of the previous paradigm, change the rules of the game and the "map" directing new research.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the scientific method:

The hypothetico-deductive model or method is a proposed description of the scientific method. According to it, scientific inquiry proceeds by formulating a hypothesis in a form that can be falsifiable, using a test on observable data where the outcome is not yet known. A test outcome that could have and does run contrary to predictions of the hypothesis is taken as a falsification of the hypothesis. A test outcome that could have, but does not run contrary to the hypothesis corroborates the theory. It is then proposed to compare the explanatory value of competing hypotheses by testing how stringently they are corroborated by their predictions.

Scientific consensus is the generally held judgment, position, and opinion of the majority or the supermajority of scientists in a particular field of study at any particular time.

The historiography of science or the historiography of the history of science is the study of the history and methodology of the sub-discipline of history, known as the history of science, including its disciplinary aspects and practices and the study of its own historical development.

In philosophy of science and epistemology, the demarcation problem is the question of how to distinguish between science and non-science. It also examines the boundaries between science, pseudoscience and other products of human activity, like art and literature and beliefs. The debate continues after more than two millennia of dialogue among philosophers of science and scientists in various fields. The debate has consequences for what can be termed "scientific" in topics such as education and public policy.

Commensurability is a concept in the philosophy of science whereby scientific theories are said to be "commensurable" if scientists can discuss the theories using a shared nomenclature that allows direct comparison of them to determine which one is more valid or useful. On the other hand, theories are incommensurable if they are embedded in starkly contrasting conceptual frameworks whose languages do not overlap sufficiently to permit scientists to directly compare the theories or to cite empirical evidence favoring one theory over the other. Discussed by Ludwik Fleck in the 1930s, and popularized by Thomas Kuhn in the 1960s, the problem of incommensurability results in scientists talking past each other, as it were, while comparison of theories is muddled by confusions about terms, contexts and consequences.

Postpositivism or postempiricism is a metatheoretical stance that critiques and amends positivism and has impacted theories and practices across philosophy, social sciences, and various models of scientific inquiry. While positivists emphasize independence between the researcher and the researched person, postpositivists argue that theories, hypotheses, background knowledge and values of the researcher can influence what is observed. Postpositivists pursue objectivity by recognizing the possible effects of biases. While positivists emphasize quantitative methods, postpositivists consider both quantitative and qualitative methods to be valid approaches.

Verificationism, also known as the verification principle or the verifiability criterion of meaning, is the philosophical doctrine which asserts that a statement is meaningful only if it is either empirically verifiable or a truth of logic.

Models of scientific inquiry have two functions: first, to provide a descriptive account of how scientific inquiry is carried out in practice, and second, to provide an explanatory account of why scientific inquiry succeeds as well as it appears to do in arriving at genuine knowledge. The philosopher Wesley C. Salmon described scientific inquiry:

The search for scientific knowledge ends far back into antiquity. At some point in the past, at least by the time of Aristotle, philosophers recognized that a fundamental distinction should be drawn between two kinds of scientific knowledge—roughly, knowledge that and knowledge why. It is one thing to know that each planet periodically reverses the direction of its motion with respect to the background of fixed stars; it is quite a different matter to know why. Knowledge of the former type is descriptive; knowledge of the latter type is explanatory. It is explanatory knowledge that provides scientific understanding of the world.

Inductivism is the traditional and still commonplace philosophy of scientific method to develop scientific theories. Inductivism aims to neutrally observe a domain, infer laws from examined cases—hence, inductive reasoning—and thus objectively discover the sole naturally true theory of the observed.

A research program is a professional network of scientists conducting basic research. The term was used by philosopher of science Imre Lakatos to blend and revise the normative model of science offered by Karl Popper's The Logic of Scientific Discovery and the descriptive model of science offered by Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Lakatos found falsificationism impractical and often not practiced, and found normal science—where a paradigm of science, mimicking an exemplar, extinguishes differing perspectives—more monopolistic than actual.

Thomas Samuel Kuhn was an American historian and philosopher of science whose 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was influential in both academic and popular circles, introducing the term paradigm shift, which has since become an English-language idiom.