A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions of the technique to refer to such images. Petroglyphs, estimated to be 20,000 years old are classified as protected monuments and have been added to the tentative list of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites. Petroglyphs are found worldwide, and are often associated with prehistoric peoples. The word comes from the Greek prefix petro-, from πέτρα petra meaning "stone", and γλύφω glýphō meaning "carve", and was originally coined in French as pétroglyphe.

The Bhimbetka rock shelters are an archaeological site in central India that spans the Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods, as well as the historic period. It exhibits the earliest traces of human life in India and evidence of the Stone Age starting at the site in Acheulian times. It is located in the Raisen District in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, about 45 kilometres (28 mi) south-east of Bhopal. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that consists of seven hills and over 750 rock shelters distributed over 10 km (6.2 mi). At least some of the shelters were inhabited more than 100,000 years ago.

Cup and ring marks or cup marks are a form of prehistoric art found in the Atlantic seaboard of Europe (Ireland, Wales, Northern England, Scotland, France, Portugal, and Spain – and in Mediterranean Europe – Italy, Azerbaijan and Greece, as well as in Scandinavia and in Switzerland.

In archaeology, rock art is human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type also may be called cave art or parietal art. A global phenomenon, rock art is found in many culturally diverse regions of the world. It has been produced in many contexts throughout human history. In terms of technique, the four main groups are:

Petroforms, also known as boulder outlines or boulder mosaics, are human-made shapes and patterns made by lining up large rocks on the open ground, often on quite level areas. Petroforms in North America were originally made by various Native American and First Nation tribes, who used various terms to describe them. Petroforms can also include a rock cairn or inukshuk, an upright monolith slab, a medicine wheel, a fire pit, a desert kite, sculpted boulders, or simply rocks lined up or stacked for various reasons. Old World petroforms include the Carnac stones and many other megalithic monuments.

The Edakkal caves are two natural caves at a remote location at Edakkal, 25 km (15.5 mi) from Kalpetta in the Wayanad district of Kerala in India. They lie 1,200 m (3,900 ft) above sea level on Ambukutty Mala, near an ancient trade route connecting the high mountains of Mysore to the ports of the Malabar Coast. Inside the caves are pictorial writings believed to date to at least 6,000 BCE, from the Neolithic man, indicating the presence of a prehistoric settlement in this region. The Stone Age carvings of Edakkal are rare and are the only known examples from South India besides those of Shenthurini, Kollam, also in Kerala. The cave paintings of Shenthurini (Shendurney) forests in Kerala are of the Mesolithic era.

Coso Rock Art District is a rock art site containing over 100,000 Petroglyphs by Paleo-Indians and/or Native Americans. The district is located near the towns of China Lake and Ridgecrest, California. Big and Little Petroglyph Canyons were declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964. In 2001, they were incorporated into this larger National Historic Landmark District. There are several other distinct canyons in the Coso Rock Art District besides the Big and Little Petroglyph Canyons. Also known as Little Petroglyph Canyon and Sand Tanks, Renegade Canyon is but one of several major canyons in the Coso Range, each hosting thousands of petroglyphs. The majority of the Coso Range images fall into one of six categories: bighorn sheep, entopic images, anthropomorphic or human-like figures, other animals, weapons & tools, and "medicine bag" images. Scholars have proposed a few potential interpretations of this rock art. The most prevalent of these interpretations is that they could have been used for rituals associated with hunting.

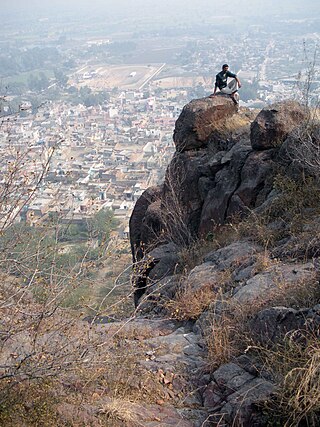

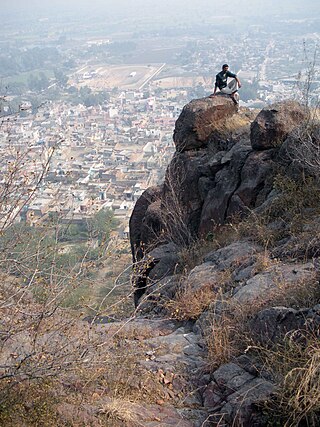

Brahmagiri is an archaeological site located in the Chitradurga district of the state of Karnataka, India. Legend has it that this is the site where sage Gautama Maharishi and his wife Ahalya lived. He was one among seven noted Hindu saints. This site was first explored by Benjamin L. Rice in 1891, who discovered rock edicts of Emperor Ashoka here. These rock edicts indicated that the locality was termed as Isila and denoted the southernmost extent of the Mauryan empire. The Brahmagiri site is a granite outcrop elevated about 180 m. above the surrounding plains and measures around 500 m east-west and 100 m north-south. It is well known for the large number of megalithic monuments that have been found here. The earliest settlement found here has been dated to at least the 2nd millennium BC.

Hallur is an archaeological site located in the Haveri district, in the Indian state of Karnataka. Hallur, South India's earliest Iron Age site, lies in a semi-arid region with scrub vegetation, located on the banks of the river Tungabhadra. The site is a small mound about 6.4 m high. The site was first discovered by Nagaraja Rao in 1962, and excavated in 1965. Further sampling was carried out in the late 1990s for the recovery of archaeobotanical evidence and new high precision radiocarbon dates

The rock drawings in Valcamonica are located in the Province of Brescia, Italy, and constitute the largest collections of prehistoric petroglyphs in the world. The collection was recognized by UNESCO in 1979 and was Italy's first recognized World Heritage Site. UNESCO has formally recognized more than 140,000 figures and symbols, but new discoveries have increased the number of catalogued incisions to between 200,000 and 300,000. The petroglyphs are spread on all surfaces of the valley, but concentrated in the areas of Darfo Boario Terme, Capo di Ponte, Nadro, Cimbergo and Paspardo.

A rock gong is a slab of rock that is hit like a drum, and is an example of a lithophone. Examples have been found in Africa, Asia, and Europe. Regional names for the rock gong include kungering, kwerent dutse, gwangalan, kungereng, kongworian, and kuge. These names are all onomatopœic, except for "kuge" which is the Hausa word for a double iron bell and "dawal" which is the Ge`ez word for a church's stone gong.

Bir Hima is a rock art site in Najran province, in southwest Saudi Arabia, about 200 kilometres (120 mi) north of the city of Najran. An ancient Palaeolithic and Neolithic site, the Bir Hima Complex covers the time period of 7000–1000 BC. Bir Hima contains numerous troughs whose type is similar from North Arabia to Yemen.

Ballari pronounced is a historic city in Bellary district in Karnataka state, India.

Hirebenakal or Hirébeṇakal or Hirébeṇakallu is a megalithic site in the state of Karnataka, India. It is among the few megalithic sites in India that can be dated to the 800 BCE to 200 BCE period. The site is located in the Koppal district, some 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) west of the town of Gangavati and some 35 kilometres (22 mi) from Hospet city. It contains roughly 400 megalithic funerary monuments, that have been dated to the transition period between Neolithic period and the Iron Age. Known locally as eḷu guḍḍagaḷu, their specific name is moryar guḍḍa. Hirebenakal is reported to be the largest necropolis among the 2000 odd megalithic sites found in South India, most of them in the state of Karnataka. Since 1955, it has been under the management of the Dharwad circle of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). On May 19, 2021, it was proposed that Hirebenakal be made a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sanganakallu is an ancient archaeological site from the Neolithic period. It is approximately 8 km from Bellary in eastern Karnataka. It is a group of hills south of a horseshoe shaped valley, with Kupgal to the north. It is one of the earliest settlements in South India, spread over 1,000 acres. There is a layer of red-brown fossilized soil spread over Sanganakallu and Kupgal that can be dated back to 9000 BC. The site is considered to be a neolithic factory site due to the surface excavation revealing large numbers of pottery, stone axes, and other stone tools. The site was first majorly excavated in 1946, by Bendapudi Subbarao, on Sannarasamma hill. Subbarao divided their culture into 3 phases:

Sidlaphadi near Badami in Karnataka, is a natural rock bridge and prehistoric rock shelter. It is located at about four km. in the middle of a shrub jungle near the historic town of Badami. A bridle and kutcha path through sandstone hills from Badami leads to Sidlaphadi and there is no metal road to the spot. Sidlaphadi literally means in Kannada the Rock of lightning, derived from gaping holes in the natural rock arch, which was formed when a lightning struck. The natural rock bridge structure looks like a wide arch between two sandstone boulders. The rock structure has large, gaping holes in the arch and allows sunlight to enter inside which provides the required light for interiors. It was also a shelter for hunter-gatherer prehistoric people.

Neolithic ashmounds are man-made landscape features found in some parts of southern India that have been dated to the Neolithic period. They have been a puzzle for long and have been the subject of many conjectures and scientific studies. They are believed to be of ritual significance and produced by early pastoral and agricultural communities by the burning of wood, dung and animal matter. Hundreds of ashmound sites have been identified and many have a low perimeter embankment and some have holes that may have held posts.

Tosham hill range, located at and in the area around Tosham, with an average elevation of 207 meters, and the rocks exposed in and around Tosham hills are part of subsurface north-western spur of Alwar group of Delhi supergroup of Aravalli Mountain Range, belong to the Precambrian Malani igneous suite of rocks and have been dated at 732 Ma BP. This range in Aravalli Craton is a remnant of the outer ring of a fallen chamber of an extinct volcano. Tosham hill range covers the hills at Tosham, Khanak, and Riwasa as well as the small rocky outcrops at Nigana, Dulehri, Dharan, Dadam, and Kharkari Makhwan. Among these, Khanak hill is the largest in area and tallest in height.

The Ambadevi rock shelters are part of an extensive cave site, where the oldest yet known traces of human life in the central province of the Indian subcontinent were discovered. The site is located in the Satpura Range of the Gawilgarh Hills in Betul District of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, north of Dharul village in Amravati district of Maharashtra. Studies of various rock paintings and petroglyphs present in the caves suggest, that the Ambadevi rock shelters were inhabited by prehistoric human settlers since around 25,000 years ago. First discoveries of clusters of numerous rock shelters and caves were made by Vijay Ingole and his team beginning on 27 January 2007. Named after the nearby ancient Ambadevi Cave Temple, the site has also been referred to as the Satpura-Tapti valley caves and the Gavilgarh-Betul rock shelters. The Ambadevi rock shelters rank among the most important archaeological discoveries of the early 21st Century in India, on par with the 20th Century discovery of the Bhimbetka rock shelters.

Gobustan Rock Art represents flora and fauna, hunting, lifestyles, and culture of pre-historic and medieval periods of time. The carvings on the rocks illustrates primitive men, ritual dances, men with lances in their hands, animals, bull fights, camel caravans, and pictures of the sun and stars. The date of these carvings goes back to 5,000 – 20,000 years before present.