The Kassites were people of the ancient Near East, who controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire c. 1531 BC and until c. 1155 BC.

Shar-Kali-Sharri was a king of the Akkadian Empire.

Kadašman-Enlil I, typically rendered mka-dáš-man-dEN.LÍL in contemporary inscriptions, was a Kassite King of Babylon from ca. 1374 BC to 1360 BC, perhaps the 18th of the dynasty. He is known to have been a contemporary of Amenhotep III of Egypt, with whom he corresponded. This places Kadašman-Enlil securely to the first half of the 14th century BC by most standard chronologies.

Nebuchadnezzar I or Nebuchadrezzar I, reigned c. 1121–1100 BC, was the fourth king of the Second Dynasty of Isin and Fourth Dynasty of Babylon. He ruled for 22 years according to the Babylonian King List C, and was the most prominent monarch of this dynasty. He is best known for his victory over Elam and the recovery of the cultic idol of Marduk.

Burna-Buriaš II, rendered in cuneiform as Bur-na- or Bur-ra-Bu-ri-ia-aš in royal inscriptions and letters, and meaning servant or protégé of the Lord of the lands in the Kassite language, where Buriaš is a Kassite storm god possibly corresponding to the Greek Boreas, was a king in the Kassite dynasty of Babylon, in a kingdom contemporarily called Karduniaš, ruling ca. 1359–1333 BC, where the Short and Middle chronologies have converged. Recorded as the 19th King to ascend the Kassite throne, he succeeded Kadašman-Enlil I, who was likely his father, and ruled for 27 years. He was a contemporary of the Egyptian Pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaten. The proverb "the time of checking the books is the shepherds' ordeal" was attributed to him in a letter to the later king Esarhaddon from his agent Mar-Issar.

The Kassite dynasty, also known as the third Babylonian dynasty, was a line of kings of Kassite origin who ruled from the city of Babylon in the latter half of the second millennium BC and who belonged to the same family that ran the kingdom of Babylon between 1595 and 1155 BC, following the first Babylonian dynasty. It was the longest known dynasty of that state, which ruled throughout the period known as "Middle Babylonian".

Kaštiliašu IV was the twenty-eighth Kassite king of Babylon and the kingdom contemporarily known as Kar-Duniaš, c. 1232–1225 BC. He succeeded Šagarakti-Šuriaš, who could have been his father, ruled for eight years, and went on to wage war against Assyria resulting in the catastrophic invasion of his homeland and his abject defeat.

Meli-Šipak II, or alternatively Melišiḫu in contemporary inscriptions, was the 33rd king of the Kassite or 3rd Dynasty of Babylon ca. 1186–1172 BC and he ruled for 15 years. Tablets with two of his year names, 4 and 10, were found at Ur. His reign marks the critical synchronization point in the chronology of the Ancient Near East.

Nazi-Maruttaš, typically inscribed Na-zi-Ma-ru-ut-ta-aš or mNa-zi-Múru-taš, Maruttašprotects him, was a Kassite king of Babylon c. 1307–1282 BC and self-proclaimed šar kiššati, or "King of the World", according to the votive inscription pictured. He was the 23rd of the dynasty, the son and successor of Kurigalzu II, and reigned for twenty six years.

Agum III was a Kassite king of Babylon ca. mid-15th century BC. Speculatively, he might figure around the 13th position in the dynastic sequence; however, this part of the Kingslist A has a lacuna, shared with the Assyrian Synchronistic Kinglist.

Kadašman-Ḫarbe I, inscribed in cuneiform contemporarily as Ka-da-áš-ma-an-Ḫar-be and meaning “he believes in Ḫarbe ,” was the 16th King of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty of Babylon, and the kingdom contemporarily known as Kar-Duniaš, during the late 15th to early 14th century, BC. It is now considered possible that he was the contemporary of Tepti Ahar, King of Elam, as preserved in a tablet found at Haft Tepe in Iran. This is dated to the “year when the king expelled Kadašman-KUR.GAL,” thought by some historians to represent him although this identification has been contested. If this name is correctly assigned to him, it would imply previous occupation of, or suzerainty over, Elam.

Kadašman-Turgu, inscribed Ka-da-aš-ma-an Túr-gu and meaning he believes in Turgu, a Kassite deity, was the 24th king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty of Babylon. He succeeded his father, Nazi-Maruttaš, continuing the tradition of proclaiming himself “king of the world” and went on to reign for eighteen years. He was a contemporary of the Hittite king Ḫattušili III, with whom he concluded a formal treaty of friendship and mutual assistance, and also Ramesses II with whom he consequently severed diplomatic relations.

Kudur-Enlil, rendered in cuneiform as Ku-durdEN.LÍL, “son of Enlil,” was the 26th king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon. He reigned into his ninth year, as attested in contemporary economic tablets. His relationship with his predecessor and successor is uncertain and does not appear in contemporary inscriptions. The personal name “Marduk is king of the gods” first appears during his reign marking the deity’s ascendancy to the head of the pantheon.

Šagarakti-Šuriaš, written phonetically ša-ga-ra-ak-ti-šur-ia-aš or dša-garak-ti-šu-ri-ia-aš in cuneiform or in a variety of other forms, Šuriašgives me life, was the twenty seventh king of the Third or Kassite dynasty of Babylon. The earliest extant economic text is dated to the 5th day of Nisan in his accession year, corresponding to his predecessor’s year 9, suggesting the succession occurred very early in the year as this month was the first in the Babylonian calendar. He ruled for thirteen years and was succeeded by his son, Kaštiliašu IV.

Enlil-nādin-šumi, inscribed mdEN.LĺL-MU-MU or mdEN.LĺL-na-din-MU, meaning “Enlil is the giver of a name,” was a king of Babylon, c. 1224 BC, following the overthrow of Kaštiliašu IV by Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria. Recorded as the 29th ruler of the Kassite dynasty, his reign was a fleeting one year, six months before he was swept from power by the invasion of the Elamite forces under the last king of the Igehalkid dynasty, Kidin-Hutran III.

Kadašman-Ḫarbe II, inscribed dKa-dáš-man-Ḫar-be, Kad-aš-man-Ḫar-be or variants and meaning I believe in Ḫarbe, the lord of the Kassite pantheon corresponding to Enlil, succeeded Enlil-nādin-šumi, as the 30th Kassite or 3rd dynasty king of Babylon. His reign was recorded as lasting only one year, six months, c. 1223 BC, as "MU 1 ITI 6" according to the Kinglist A, a formula which is open to interpretation.

Adad-šuma-uṣur, inscribed dIM-MU-ŠEŠ, meaning "O Adad, protect the name!," and dated very tentatively ca. 1216–1187 BC, was the 32nd king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon and the country contemporarily known as Karduniaš. His name was wholly Babylonian and not uncommon, as for example the later Assyrian King Esarhaddon had a personal exorcist, or ašipu, with the same name who was unlikely to have been related. He is best known for his rude letter to Aššur-nirari III, the most complete part of which is quoted below, and was enthroned following a revolt in the south of Mesopotamia when the north was still occupied by the forces of Assyria, and he may not have assumed authority throughout the country until around the 25th year of his 30-year reign, although the exact sequence of events and chronology remains disputed.

Shu-Ilishu was the 2nd ruler of the dynasty of Isin. He reigned for 10 years Shu-Ilishu was preceded by Išbi-erra. Iddin-Dagān then succeeded Shu-Ilishu. Shu-Ilishu is best known for his retrieval of the cultic idol of Nanna from the Elamites and its return to Ur.

The office of šandabakku, inscribed 𒇽𒄘𒂗𒈾 (LÚGÚ.EN.NA) or sometimes as 𒂷𒁾𒁀𒀀𒂗𒆤𒆠, the latter designation perhaps meaning "archivist of Enlil," was the name of the position of governor of the Mesopotamian city of Nippur from the Kassite period onward. Enlil, as the tutelary deity of Nippur, had been elevated in prominence and was shown special veneration by the Kassite monarchs, it being the most common theophoric element in their names. This caused the position of the šandabakku to become very prestigious and the holders of the office seem to have wielded influence second only to the king.

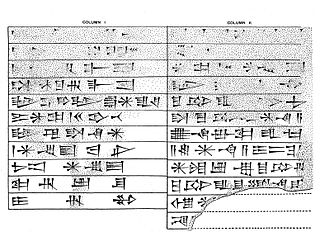

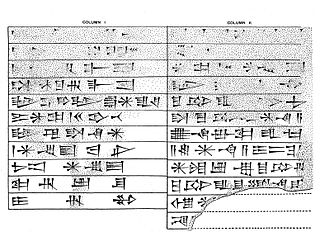

The Enlil-bānī land grant kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian narû ša ḫaṣbi, or clay stele, recording the confirmation of a beneficial grant of land by Kassite king Kadašman-Enlil I or Kadašman-Enlil II to one of his officials. It is actually a terra-cotta cone, extant with a duplicate, the orientation of whose inscription, perpendicular to the direction of the cone, in two columns and with the top facing the point, indicates it was to be erected upright,, like other entitlement documents of the period.