A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Ostracism was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the citizen, ostracism was often used preemptively. It was used as a way of neutralizing someone thought to be a threat to the state or a potential tyrant, though in many cases popular opinion often informed the expulsion. The word "ostracism" continues to be used for various forms of shunning.

The Trial of Socrates was held to determine the philosopher's guilt of two charges: asebeia (impiety) against the pantheon of Athens, and corruption of the youth of the city-state; the accusers cited two impious acts by Socrates: "failing to acknowledge the gods that the city acknowledges" and "introducing new deities".

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence, make findings of fact, and render an impartial verdict officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment.

Solon was an archaic Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet. He is one of the Seven Sages of Greece and credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. Solon's efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline resulted in his constitutional reform overturning most of Draco's laws.

The Solonian constitution was created by Solon in the early 6th century BC. At the time of Solon, the Athenian State was almost falling to pieces in consequence of dissensions between the parties into which the population was divided. Solon wanted to revise or abolish the older laws of Draco. He promulgated a code of laws embracing the whole of public and private life, the salutary effects of which lasted long after the end of his constitution.

The Areopagus is a prominent rock outcropping located northwest of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Its English name is the Late Latin composite form of the Greek name Areios Pagos, translated "Hill of Ares". The name Areopagus also referred, in classical times, to the Athenian governing council, later restricted to the Athenian judicial council or court that tried cases of deliberate homicide, wounding, and religious matters, as well as cases involving arson of olive trees, because they convened in this location. The war god Ares was supposed to have been tried by the other gods on the Areopagus for the murder of Poseidon's son Halirrhothius.

Critias was an ancient Athenian poet, philosopher and political leader. He is known today for being a student of Socrates, a writer of some regard, and for becoming the leader of the Thirty Tyrants, who ruled Athens for several months after the conclusion of the Peloponnesian War in 404/403.

The Thirty Tyrants were an oligarchy that briefly ruled Athens from 405 BC - 404 BC. Installed into power by the Spartans after the Athenian surrender in the Peloponnesian War, the Thirty became known for their tyrannical rule, first being called "The Thirty Tyrants" by Polycrates. Although they maintained power for only eight months, their reign resulted in the killing of 5% of the Athenian population, the confiscation of citizens' property and the exile of other democratic supporters.

Cleisthenes, or Clisthenes, was an ancient Athenian lawgiver credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508 BC. For these accomplishments, historians refer to him as "the father of Athenian democracy". He was a member of the aristocratic Alcmaeonid clan. He was the younger son of Megacles and Agariste making him the maternal grandson of the tyrant Cleisthenes of Sicyon. He was also credited with increasing the power of the Athenian citizens' assembly and for reducing the power of the nobility over Athenian politics.

Not proven is a verdict available to a court of law in Scotland. Under Scots law, a criminal trial may end in one of three verdicts, one of conviction ("guilty") and two of acquittal.

The Apology of Socrates, written by Plato, is a Socratic dialogue of the speech of legal self-defence which Socrates spoke at his trial for impiety and corruption in 399 BC.

Ancient Greek laws consist of the laws and legal institutions of ancient Greece.

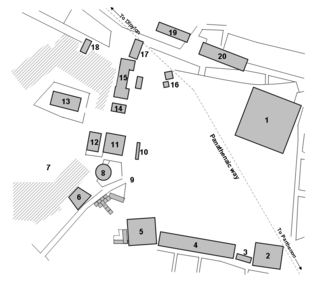

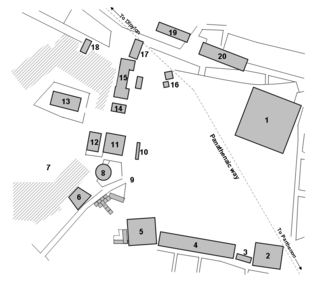

Stoa Basileios, meaning Royal Stoa, was a Doric stoa in the northwestern corner of the Athenian Agora, which was built in the 6th century BC, substantially altered in the 5th century BC, and then carefully preserved until the mid-second century AD. It is among the smallest known Greek stoas, but had great symbolic significance as the seat of the Athenian King Archon, repository of Athens' laws, and site of "the stone" on which incoming magistrates swore their oath of office.

Heliaia or Heliaea was the supreme court of ancient Athens. The view generally held among scholars is that the court drew its name from the ancient Greek verb ἡλιάζεσθαι, which means congregate. Another version is that the court took its name from the fact that the hearings were taking place outdoors, under the sun. Initially, this was the name of the place where the hearings were convoked, but later this appellation included the court as well.

A kleroterion was a randomization device used by the Athenian polis during the period of democracy to select citizens to the boule, to most state offices, to the nomothetai, and to court juries.

The graphḗ paranómōn, was a form of legal action believed to have been introduced at Athens under the democracy sometime around the year 415 BC; it has been seen as a replacement for ostracism, which fell into disuse around the same time, although this view is not held by David Whitehead, who points out that the graphe paranomon was a legal procedure with legal ramifications, including shame, and the convicted had officially committed a crime, whereas the ostrakismos was not shameful in the least.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient Greece:

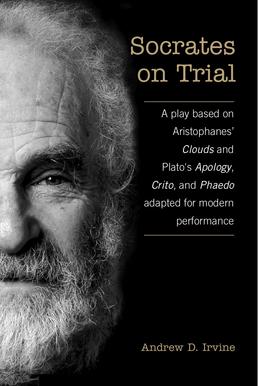

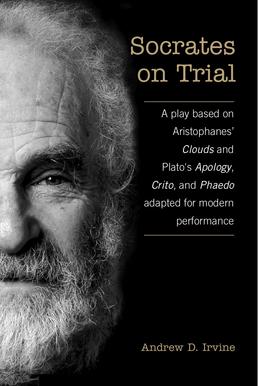

Socrates on Trial is a play depicting the life and death of the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates. It tells the story of how Socrates was put on trial for corrupting the youth of Athens and for failing to honour the city's gods. The play contains adaptations of several classic Greek works: the slapstick comedy, Clouds, written by Aristophanes and first performed in 423 BCE; the dramatic monologue, Apology, written by Plato to record the defence speech Socrates gave at his trial; and Plato's Crito and Phaedo, two dialogues describing the events leading to Socrates’ execution in 399 BCE. The play was written by Andrew David Irvine of the University of British Columbia and premiered by director Joan Bryans of Vital Spark Theatre Company in 2007 at the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts in Vancouver.

Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century BC in the Greek city-state of Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. Although Athens is the most famous ancient Greek democratic city-state, it was not the only one, nor was it the first; multiple other city-states adopted similar democratic constitutions before Athens. By the late 4th century BC, as many as half of the over one thousand existing Greek cities might have been democracies. Athens practiced a political system of legislation and executive bills. Participation was open to adult, free male citizens The metics probably constituted no more than 30 percent of the total adult population.