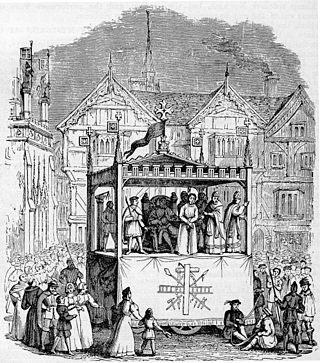

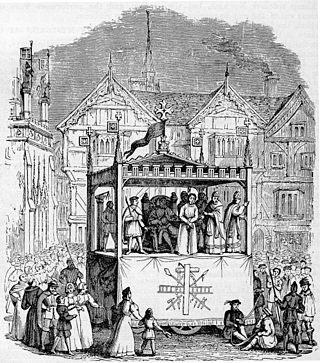

Mystery plays and miracle plays are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphonal song. They told of subjects such as the Creation, Adam and Eve, the murder of Abel, and the Last Judgment. Often they were performed together in cycles which could last for days. The name derives from mystery used in its sense of miracle, but an occasionally quoted derivation is from ministerium, meaning craft, and so the 'mysteries' or plays performed by the craft guilds.

Old French was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligible yet diverse, spoken in the northern half of France. These dialects came to be collectively known as the langue d'oïl, contrasting with the langue d'oc in the south of France. The mid-14th century witnessed the emergence of Middle French, the language of the French Renaissance in the Île de France region; this dialect was a predecessor to Modern French. Other dialects of Old French evolved themselves into modern forms, each with its own linguistic features and history.

A sacred language, holy language or liturgical language is any language that is cultivated and used primarily for religious reasons by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language." It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people who are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, normally spoken informally rather than written, and seen as of lower status than more codified forms. It may vary from more prestigious speech varieties in different ways, in that the vernacular can be a distinct stylistic register, a regional dialect, a sociolect, or an independent language. Vernacular is a term for a type of speech variety, generally used to refer to a local language or dialect, as distinct from what is seen as a standard language. The vernacular is contrasted with higher-prestige forms of language, such as national, literary, liturgical or scientific idiom, or a lingua franca, used to facilitate communication across a large area.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

The Latin school was the grammar school of 14th- to 19th-century Europe, though the latter term was much more common in England. Emphasis was placed, as the name indicates, on learning to use Latin. The education given at Latin schools gave great emphasis to the complicated grammar of the Latin language, initially in its Medieval Latin form. Grammar was the most basic part of the trivium and the Liberal arts — in artistic personifications Grammar's attribute was the birch rod. Latin school prepared students for university, as well as enabling those of middle class status to rise above their station. It was therefore not unusual for children of commoners to attend Latin schools, especially if they were expected to pursue a career within the church. Although Latin schools existed in many parts of Europe in the 14th century and were more open to the laity, prior to that the Church allowed for Latin schools for the sole purpose of training those who would one day become clergymen. Latin schools began to develop to reflect Renaissance humanism around the 1450s. In some countries, but not England, they later lost their popularity as universities and some Catholic orders began to prefer the vernacular.

The Junius manuscript is one of the four major codices of Old English literature. Written in the 10th century, it contains poetry dealing with Biblical subjects in Old English, the vernacular language of Anglo-Saxon England. Modern editors have determined that the manuscript is made of four poems, to which they have given the titles Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, and Christ and Satan. The identity of their author is unknown. For a long time, scholars believed them to be the work of Cædmon, accordingly calling the book the Cædmon manuscript. This theory has been discarded due to the significant differences between the poems.

The Abbey of St Mary is a ruined Benedictine abbey in York, England and a scheduled monument.

The N-Town Plays are a cycle of 42 medieval Mystery plays from between 1450 and 1500.

The term Middle English literature refers to the literature written in the form of the English language known as Middle English, from the late 12th century until the 1470s. During this time the Chancery Standard, a form of London-based English became widespread and the printing press regularized the language. Between the 1470s and the middle of the following century there was a transition to early Modern English. In literary terms, the characteristics of the literary works written did not change radically until the effects of the Renaissance and Reformed Christianity became more apparent in the reign of King Henry VIII. There are three main categories of Middle English literature, religious, courtly love, and Arthurian, though much of Geoffrey Chaucer's work stands outside these. Among the many religious works are those in the Katherine Group and the writings of Julian of Norwich and Richard Rolle.

Medieval French literature is, for the purpose of this article, Medieval literature written in Oïl languages during the period from the eleventh century to the end of the fifteenth century.

Layamon's Brut, also known as The Chronicle of Britain, is a Middle English poem compiled and recast by the English priest Layamon. Layamon's Brut is 16,096 lines long and narrates the history of Britain. It is the first historiography written in English since the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Named for Britain's mythical founder, Brutus of Troy, the poem is largely based on the Anglo-Norman French Roman de Brut by Wace, which is in turn a version of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin Historia Regum Britanniae. Layamon's poem, however, is longer than both and includes an enlarged section on the life and exploits of King Arthur. It is written in the alliterative verse style commonly used in Middle English poetry by rhyming chroniclers, the two halves of the alliterative lines being often linked by rhyme as well as by alliteration.

Medieval theatre encompasses theatrical performance in the period between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century and the beginning of the Renaissance in approximately the 15th century. The category of "medieval theatre" is vast, covering dramatic performance in Europe over a thousand-year period. A broad spectrum of genres needs to be considered, including mystery plays, morality plays, farces and masques. The themes were almost always religious. The most famous examples are the English cycle dramas, the York Mystery Plays, the Chester Mystery Plays, the Wakefield Mystery Plays, and the N-Town Plays, as well as the morality play known as Everyman. One of the first surviving secular plays in English is The Interlude of the Student and the Girl.

The Play of Daniel, or Ludus Danielis, is either of two medieval Latin liturgical dramas based on the biblical Book of Daniel, one of which is accompanied by monophonic music.

"I syng of a mayden" is a Middle English lyric poem or carol of the 15th century celebrating the Annunciation and the Virgin Birth of Jesus. It has been described as one of the most admired short vernacular English poems of the late Middle Ages.

Anglo-Norman, also known as Anglo-Norman French, was a dialect of Old Norman French that was used in England and, to a lesser extent, elsewhere in Great Britain and Ireland during the Anglo-Norman period.

The Harrowing of Hell is an eighth-century Latin work in fifty-five lines found in the Anglo-Saxon Book of Cerne. It is probably a Northumbrian work, written in prose and verse, where the former serves either as a set of stage directions for a dramatic portrayal or as a series of narrations for explaining the poetry.

Sponsus or The Bridegroom is a medieval Latin and Occitan dramatic treatment of Jesus' parable of the ten virgins. A liturgical play designed for Easter Vigil, it was composed probably in Gascony or western Languedoc in the mid-eleventh century. Its scriptural basis is found in the Gospel of Matthew (25:1–13), but it also draws on the Song of Songs and the Patristics, perhaps Jerome's Adversus Jovinianum. In certain respects—the portrayal of the merchants, the spilling of the oil, the implicit questioning of accepted theodicy—it is original and dramatically powerful.

Bible translations in the Middle Ages discussions are rare in contrast to Late Antiquity, when the Bibles available to most Christians were in the local vernacular. In a process seen in many other religions, as languages changed, and in Western Europe languages with no tradition of being written down became dominant, the prevailing vernacular translations remained in place, despite gradually becoming sacred languages, incomprehensible to the majority of the population in many places. In Western Europe, the Latin Vulgate, itself originally a translation into the vernacular, was the standard text of the Bible, and full or partial translations into a vernacular language were uncommon until the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period.

The Lament of Edward II is traditionally credited to Edward II of England, and thought to have been written during his imprisonment shortly after he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. Not all readers are convinced of the royal attribution of its authorship. The poem, in fifteen stanzas, bears the heading De Le Roi Edward, le Fiz Roi Edward, Le Chanson Qe Il Fist Mesmes. It was a chanson, and was likely to be sung to an existing tune. In each stanza two rhymes alternate, in approximately octosyllabic lines. The text survives in a manuscript on vellum at Longleat, bound into a volume titled Tractatus varii Theologici saec. XIII et XIV, causing it to be overlooked; and in a manuscript in the Royal Library. It was identified by Paul Studer and first published by him with a short literary introduction and an English translation in 1921.