Related Research Articles

The League of Nations was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. The main organization ceased operations on 20 April 1946 when many of its components were relocated into the new United Nations.

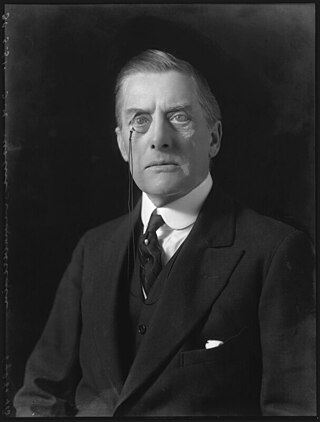

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, was a British statesman and Conservative politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, from May 1923 to January 1924, from November 1924 to June 1929, and from June 1935 to May 1937.

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political alliance with the Conservative Party in opposition to Irish Home Rule. The two parties formed the ten-year-long coalition Unionist Government 1895–1905 but kept separate political funds and their own party organisations until a complete merger between the Liberal Unionist and the Conservative parties was agreed to in May 1912.

Appeasement, in an international context, is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the British governments of Prime Ministers Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain towards Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy between 1935 and 1939. Under British pressure, appeasement of Nazism and Fascism also played a role in French foreign policy of the period but was always much less popular there than in the United Kingdom.

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly Conservative Party leader before serving as Foreign Secretary.

Edgar Algernon Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood,, known as Lord Robert Cecil from 1868 to 1923, was a British lawyer, politician and diplomat. He was one of the architects of the League of Nations and a defender of it, whose service to the organisation saw him awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1937.

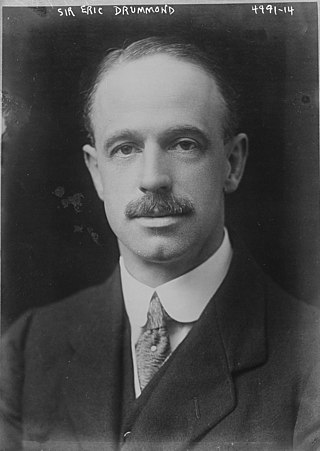

James Eric Drummond, 7th Earl of Perth,, was a British politician and diplomat who was the first Secretary-General of the League of Nations (1920–1933).

Sir Charles Kingsley Webster was a British diplomat and historian. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, Crosby and King's College, Cambridge. After leaving Cambridge University, he went on to become a professor at Harvard, Oxford, and the London School of Economics (LSE). He also served as President of the British Academy from 1950 to 1954.

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) is a non-profit non-governmental organization working "to bring together women of different political views and philosophical and religious backgrounds determined to study and make known the causes of war and work for a permanent peace" and to unite women worldwide who oppose oppression and exploitation. WILPF has national sections in 37 countries.

The Peace Ballot of 1934–35 was a nationwide questionnaire in Britain of five questions attempting to discover the British public's attitude to the League of Nations and collective security. Its official title was "A National Declaration on the League of Nations and Armaments." Advocates of the League of Nations felt that a growing isolationism in Britain had to be countered by a massive demonstration that the public demanded adherence to the principles of the League. Recent failures to achieve disarmament had undermined the credibility of the League, and there were fears the National government might step back from its official stance of supporting the League.

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and promoting world peace. He was a leading advocate of the League of Nations to enable the international community to avoid wars and end hostile aggression. Wilsonianism is a form of liberal internationalism.

LNU may refer to:

The No More War Movement was the name of two pacifist organisations, one in the United Kingdom and one in New Zealand.

Sir Alfred Eckhard Zimmern was an English classical scholar, historian, and political scientist writing on international relations. A British policymaker during World War I and a prominent liberal thinker, Zimmern played an important role in drafting the blueprint for what would become the League of Nations.

The Big Four or the Four Nations refer to the four top Allied powers of World War I and their leaders who met at the Paris Peace Conference in January 1919. The Big Four is also known as the Council of Four. It was composed of Georges Clemenceau of France, David Lloyd George of the United Kingdom, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando of Italy, and Woodrow Wilson of the United States.

The Carlton Club meeting, on 19 October 1922, was a formal meeting of Members of Parliament who belonged to the Conservative Party, called to discuss whether the party should remain in government in coalition with a section of the Liberal Party under the leadership of Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The party leadership favoured continuing, but the party rebels led by Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin argued that participation was damaging the party. The meeting voted decisively against the Coalition, which resulted in its collapse, the resignation of Austen Chamberlain as party leader, and the invitation of Law to form a Government. The Conservatives subsequently won the general election with an overall majority.

The 1933 Skipton by-election was a parliamentary by-election for the British House of Commons constituency of Skipton on 7 November 1933.

Dora West (1883–1962) O.B.E., was a British Liberal Party politician and one of the founders of the League of Nations Union.

The Anti-Nazi Council was a London-based organisation of the 1930s. Initially part of the left-wing anti-fascist movement, it gained political significance when allied to Winston Churchill, though at the time its influence was largely covert. Between around 1935 and 1937 it was a vehicle for Churchill's attempts to form a cross-party alliance against appeasement of the fascist dictatorships. The group behind it used the title Focus in Defence of Freedom and Peace, and variants, and is sometimes known as the Focus Group.

The United Kingdom and the League of Nations played central roles in the diplomatic history of the interwar period 1920-1939 and the search for peace. British activists and political leaders helped plan and found the League of Nations, provided much of the staff leadership, and Britain played a central role in most of the critical issues facing the League. The League of Nations Union was an important private organization that promoted the League in Britain. By 1924 the League was broadly popular and was featured in election campaigns. The Liberals were most supportive; the Conservatives least so. From 1931 onward, major aggressions by Japan, Italy, Spain and Germany effectively ruined the League in British eyes.

References

- ↑ Douglas, R. M. (2004). The Labour Party, Nationalism and Internationalism, 1939-1951: A New World Order. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9780203505786.

- 1 2 "League of Nations Union Collected Records, 1915-1945". Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

- ↑ Callaghan, John T. (2007). The Labour Party and Foreign Policy: A History. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 9781134540150.

- ↑ Baratta, Joseph Preston (2004). Politics of World Federation: From world federalism to global governance. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 74. ISBN 9780275980689.

- 1 2 3 "LNU - League of Nations Union Collection". LSE Library Services.

- ↑ Summy, Hilary (2007). From hope ... to hope : story of the Australian League of Nations union, featuring the Victorian Branch, 1921-1945 (PhD thesis). The University of Queensland.

- ↑ Phelps, Edith M. (1919). Selected Articles on a League of Nations. New York: H. W. Wilson & Company. pp. xxvi & xxxvii.

- 1 2 Archives of League Of Nations Union, 1918-1971. Archived 2012-07-15 at archive.today

- ↑ McKercher, B. J. C., ed. (1990). Anglo-American Relations in the 1920s: The Struggle for Supremacy. University of Alberta. p. 23. ISBN 9781349119196.

- ↑ McDonough, Frank (1998). Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement, and the British Road to War. Manchester University Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780719048326.

- ↑ Peter Wilson, "Gilbert Murray and International Relations: Hellenism, liberalism, and international intellectual cooperation as a path to peace." Review of International Studies 37.2 (2011): 881-909. online

- ↑ Dutton, David (1985). Austen Chamberlain: Gentleman in Politics. New Brunswick: Transaction. p. 307.

- ↑ Thompson, J. A. (December 1977). "Lord Cecil and the Pacifists in the League of Nations Union". The Historical Journal. Cambridge University Press. 20 (4): 949–59. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00011481. JSTOR 2638416. S2CID 154899222.

- ↑ Thompson, Neville (1971). The Anti-Appeasers: Conservative Opposition to Appeasement in the 1930s. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780198214878.

- ↑ HC Deb 23 November 1932 vol 272 cc73-211

- ↑ Thane, Pat (2001). Cassell's Companion to Twentieth-Century Britain. Cassell. p. 311. ISBN 9780304347940.

- ↑ Cook, Chris (1975). Sources in British Political History, 1900-1950 Volume 1. London: MacMillan. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-333-15036-8.

- ↑ British Library of Political and Economic Science, League of Nations Union, 1918-1971. Archived 2012-07-14 at archive.today

- ↑ "Peace and Internationalism Digitised Collection". LSE Digital Library. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)