Related Research Articles

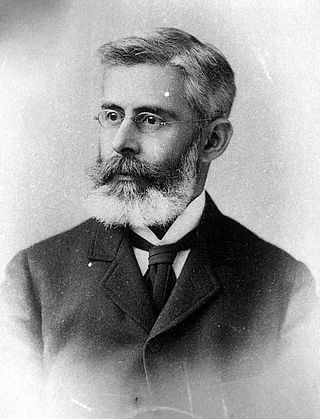

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria and trypanosomiasis. Following his father, Louis Théodore Laveran, he took up military medicine as his profession. He obtained his medical degree from University of Strasbourg in 1867.

Theobald Smith FRS(For) HFRSE was a pioneering epidemiologist, bacteriologist, pathologist and professor. Smith is widely considered to be America's first internationally-significant medical research scientist.

Walter Reed was a U.S. Army physician who in 1901 led the team that confirmed the theory of Cuban doctor Carlos Finlay that yellow fever is transmitted by a particular mosquito species rather than by direct contact. This insight gave impetus to the new fields of epidemiology and biomedicine, and most immediately allowed the resumption and completion of work on the Panama Canal (1904–1914) by the United States. Reed followed work started by Finlay and directed by George Miller Sternberg, who has been called the "first U.S. bacteriologist".

One of the greatest challenges facing the builders of the Panama Canal was dealing with the tropical diseases rife in the area. The health measures taken during the construction contributed greatly to the success of the canal's construction. These included general health care, the provision of an extensive health infrastructure, and a major program to eradicate disease-carrying mosquitoes from the area.

Carlos Juan Finlay was a Cuban epidemiologist recognized as a pioneer in the research of yellow fever, determining that it was transmitted through mosquitoes Aedes aegypti.

William Crawford Gorgas KCMG was a United States Army physician and 22nd Surgeon General of the U.S. Army (1914–1918). He is best known for his work in Florida, Havana and at the Panama Canal in abating the transmission of yellow fever and malaria by controlling the mosquitoes that carry these diseases. At the time, his strategy was greeted with considerable skepticism and opposition to such hygiene measures. However, the measures he put into practice as the head of the Panama Canal Zone Sanitation Commission saved thousands of lives and contributed to the success of the Canal's construction.

Jesse William Lazear was an American physician.

Frederick Vincent Theobald FES was an English entomologist and "distinguished authority on mosquitoes". During his career, he was responsible for the economic zoology section of the Natural History Museum, London, vice-principal of the South-Eastern Agricultural College at Wye, Kent, Professor of Agricultural Zoology at London University, and advisory entomologist to the Board of Agriculture for the South-Eastern district of England. He wrote a five volume monograph and sixty scientific papers on mosquitoes. He was recognised for his work in entomology, tropical medicine, and sanitation; awards for his work include the Imperial Ottoman Order of Osmanieh, the Mary Kingsley Medal, and the Victoria Medal of Honour, as well as honorary fellowships of learned societies.

During the 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic in Philadelphia, 5,000 or more people were listed in the official register of deaths between August 1 and November 9. The vast majority of them died of Yellow Fever, making the epidemic in the city of 50,000 people one of the most severe in United States history. By the end of September, 20,000 people had fled the city, including congressional and executive officials of the federal government. Most did not return until after the epidemic had abated in late November. The mortality rate peaked in October before frost finally killed the mosquitoes and brought an end to the outbreak. Doctors tried a variety of treatments but knew neither the origin of the fever nor that the disease was transmitted by mosquitoes.

The history of malaria extends from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent except Antarctica. Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the Plasmodium parasites which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoes which transmit the parasites.

Disease in colonial America that afflicted the early immigrant settlers was a dangerous threat to life. Some of the diseases were new and treatments were ineffective. Malaria was deadly to many new arrivals, especially in the Southern colonies. Of newly arrived able-bodied young men, over one-fourth of the Anglican missionaries died within five years of their arrival in the Carolinas. Mortality was high for infants and small children, especially for diphtheria, smallpox, yellow fever, and malaria. Most sick people turned to local healers, and used folk remedies. Others relied upon the minister-physicians, barber-surgeons, apothecaries, midwives, and ministers; a few used colonial physicians trained either in Britain, or an apprenticeship in the colonies. One common treatment was blood letting. The method was crude due to a lack of knowledge about infection and disease among medical practitioners. There was little government control, regulation of medical care, or attention to public health. By the 18th century, Colonial physicians, following the models in England and Scotland, introduced modern medicine to the cities in the 18th century, and made some advances in vaccination, pathology, anatomy and pharmacology.

Juan Guitéras y Gener, was a Cuban physician and pathologist specializing in yellow fever.

Stanley Jennings Carpenter, Colonel, U.S. Army, retired, deceased, a noted medical entomologist, was born December 9, 1904, in West Liberty, Morgan County, Kentucky, and died on August 28, 1984, at Santa Rosa, California at age 79. This biographical sketch is based on the text of a memorial lecture presented by a colleague on March 24, 1997.

The history of Uxbridge, Massachusetts, founded in 1727, may be divided into its prehistory, its colonial history and its modern industrial history. Uxbridge is located on the Massachusetts-Rhode Island state line, and became a center of the earliest industrialized region in the United States.

William Alexander Young MB, CHB, DPH, DTM was a Scottish doctor and surgeon who specialised in tropical medicine. He spent most of his career in West Africa, as a pathologist and bacteriologist with the West African Medical Service, where he studied many of the endemic diseases. The majority of his research was carried out in Nigeria and later at Accra, Gold Coast. He is remembered particularly as having done much to further the understanding of the nature and epidemiology of yellow fever. He died aged 38 of yellow fever, during the course of his research.

Israel Jacob Kligler was a microbiologist. A Zionist and humanist, he was born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, educated in the United States and spent most of his career in Mandatory Palestine, but died before the creation of the State of Israel. He was one of the first four professors of the Hebrew University and the founder of Department of Hygiene and Bacteriology of the university, which he headed until his death in 1944. Kligler was one of the pioneers of modern medical research in Mandatory Palestine, studying as varied a field as Bacteriology, Parasitology, Virology, Nutrition, Epidemiology and Public Health. He developed the Kligler Iron Agar medium for the isolation and identification of intestinal bacteria, which is still in use today.

Dr EA Koch Memorial is a heritage-listed memorial at Abbot Street, Cairns City, Cairns, Cairns Region, Queensland, Australia. It was designed by Melrose & Fenwick and built in 1903. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 27 May 1997.

Edward Albert Koch (1843-1901) was a German-born medical practitioner in Cairns, Queensland, Australia, known for his treatment of malaria and his early recognition of the role played by mosquitoes in transmitting the disease. Dr Koch's fever remedy and preventative measures played a significant role in controlling endemic malaria in far North Queensland in the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century.

John Payne Woodall (1935–2016), known as Jack Woodall, was an American-British entomologist and virologist who made significant contributions to the study of arboviruses in South America, the Caribbean and Africa. He did research on the causative agents of dengue fever, Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever, o'nyong'nyong fever, yellow fever, Zika fever, and others.

References

- ↑ Shrady, George F, ed. (1885). "Medical Record, A Weekly Journal of Medicine and Surgery", Vol 28, No 24, December 12, 1885. New York City: William Wood & Company. p. 651.

- ↑ "A History of Mosquitoes in Massachusetts, by Curtis R. Best". Northeast mosquito control association. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ 'Annual Report of the State Board of Health of Massachusetts. 1905. p. 52.

- ↑ Wrona, B. Mae., Uxbridge, Images of America; 2000; Arcadia Publishing Company; ISBN 0-7385-0461-0