The Book of Esther, also known in Hebrew as "the Scroll", is a book in the third section of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Scrolls in the Hebrew Bible and later became part of the Christian Old Testament. The book relates the story of a Jewish woman in Persia, born as Hadassah but known as Esther, who becomes queen of Persia and thwarts a genocide of her people.

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Israelites. The second division of Christian Bibles is the New Testament, written in Koine Greek.

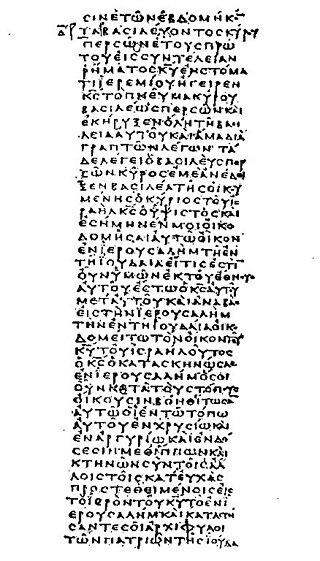

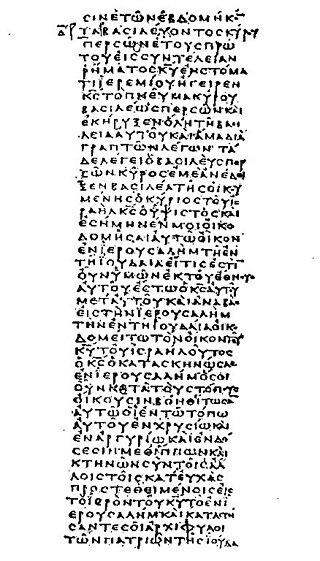

The Septuagint, sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy, and often abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Hebrew. The full Greek title derives from the story recorded in the Letter of Aristeas to Philocrates that "the laws of the Jews" were translated into the Greek language at the request of Ptolemy II Philadelphus by seventy-two Hebrew translators—six from each of the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

The Bible has been translated into many languages from the biblical languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. As of September 2023 all of the Bible has been translated into 736 languages, the New Testament has been translated into an additional 1,658 languages, and smaller portions of the Bible have been translated into 1,264 other languages according to Wycliffe Global Alliance. Thus, at least some portions of the Bible have been translated into 3,658 languages.

Demetrius of Phalerum was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophrastus, and perhaps of Aristotle, he was one of the first members of the Peripatetic school of philosophy. Demetrius had been a distinguished statesman who was appointed by Cassander, the King of Macedon, to govern Athens, where Demetrius ruled as sole ruler for ten years. During this time, he introduced important reforms of the legal system, while also maintaining pro-Cassander oligarchic rule.

1 Maccabees, also known as the First Book of Maccabees, First Maccabees, and abbreviated as 1 Macc., is a deuterocanonical book which details the history of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire as well as the founding and earliest history of the independent Hasmonean kingdom. It describes the promulgation of decrees forbidding traditional Jewish practices by King Antiochus IV Epiphanes and the formation of a rebellion against him by Mattathias of the Hasmonean family and his five sons. Mattathias's son Judas Maccabeus takes over the revolt and the rebels as a group are called the Maccabees; the book chronicles in detail the successes and setbacks of the rebellion. While Judas is eventually killed in battle, the Maccabees eventually achieve autonomy and then independence for Judea under the leadership of the Hasmonean family. Judas's brother Simon Thassi is declared High Priest by will of the Jewish people. The time period described is from around 170 BC to 134 BC.

2 Maccabees, also known as the Second Book of Maccabees, Second Maccabees, and abbreviated as 2 Macc., is a deuterocanonical book which recounts the persecution of Jews under King Antiochus IV Epiphanes and the Maccabean Revolt against him. It concludes with the defeat of the Seleucid Empire general Nicanor in 161 BC by Judas Maccabeus, the leader of the Maccabees.

3 Maccabees, also called the Third Book of Maccabees, is a book written in Koine Greek, likely in the 1st century BC in either the late Ptolemaic period of Egypt or in early Roman Egypt. Despite the title, the book has nothing to do with the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire described in 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees. Instead it tells the story of a persecution of the Jews under Pharaoh Ptolemy IV Philopator in Ptolemaic Egypt, some decades before the Maccabee uprising in Judea. The story purports to explain the origin of a Purim-like festival celebrated in Egypt. 3 Maccabees is somewhat similar to the Book of Esther, another book which describes how a king is advised to annihilate the Diaspora Jews in his territory, yet is thwarted by God.

The Letter of Jeremiah, also known as the Epistle of Jeremiah, is a deuterocanonical book of the Old Testament; this letter is attributed to Jeremiah and addressed to the Jews who were about to be carried away as captives to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar. It is included in Roman Catholic Bibles as the final chapter of the Book of Baruch. It is also included in Orthodox Bibles as a separate book, as well as in the Apocrypha of the Authorized Version.

The Alexandrian school is a collective designation for certain tendencies in literature, philosophy, medicine, and the sciences that developed in the Hellenistic cultural center of Alexandria, Egypt during the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

In contrast to the variety of absolute or personal names of God in the Old Testament, the New Testament uses only two, according to the International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia. From the 20th century onwards, "a number of scholars find various evidence for the name [YHWH or related form] in the New Testament.

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Hellenistic culture. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellenistic Judaism were Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria, the two main Greek urban settlements of the Middle East and North Africa, both founded in the end of the fourth century BCE in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great. Hellenistic Judaism also existed in Jerusalem during the Second Temple Period, where there was a conflict between Hellenizers and traditionalists.

There is no scholarly consensus as to when the canon of the Hebrew Bible was fixed. Rabbinic Judaism recognizes the twenty-four books of the Masoretic Text as the authoritative version of the Tanakh. Of these books, the Book of Daniel has the most recent final date of composition. The canon was therefore fixed at some time after this date. Some scholars argue that it was fixed during the Hasmonean dynasty, while others argue it was not fixed until the second century CE or even later.

Biblical languages are any of the languages employed in the original writings of the Bible. Partially owing to the significance of the Bible in society, Biblical languages are studied more widely than many other dead languages. Furthermore, some debates exist as to which language is the original language of a particular passage, and about whether a term has been properly translated from an ancient language into modern editions of the Bible. Scholars generally recognize three languages as original biblical languages: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek.

The Ptolemaic Baris was a citadel maintained by Ptolemaic Egypt during its rule of Jerusalem in the 3rd century BC. Described by only a few ancient sources, no archaeological remains of the citadel have been found and much about it remains a matter of conjecture.

Demetrius the Chronographer was a Jewish chronicler (historian) of the late 3rd century BCE, who lived probably in Alexandria and wrote in Greek.

The New Testament was written in a form of Koine Greek, which was the common language of the Eastern Mediterranean from the conquests of Alexander the Great until the evolution of Byzantine Greek.

Jewish Koine Greek, or Jewish Hellenistic Greek, is the variety of Koine Greek or "common Attic" found in a number of Alexandrian dialect texts of Hellenistic Judaism, most notably in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible and associated literature, as well as in Greek Jewish texts from Palestine. The term is largely equivalent with Greek of the Septuagint as a cultural and literary rather than a linguistic category. The minor syntax and vocabulary variations in the Koine Greek of Jewish authors are not as linguistically distinctive as the later language Yevanic, or Judeo-Greek, spoken by the Romaniote Jews in Greece.

Eleazar was a Jewish High Priest during the Second Temple period. He was the son of Onias I and brother of Simon I.

Sarah J. K. Pearce is Ian Karten Professor of History and Head of the School of Humanities at the University of Southampton. She is known in particular for her work on Jews in the Hellenistic world and the Roman Empire, especially the life and work of Philo of Alexandria.