The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world.

Michael Gorman is a British-born librarian, library scholar and editor/writer on library issues noted for his traditional views. During his tenure as president of the American Library Association (ALA), he was vocal in his opinions on a range of subjects, notably technology and education. He currently lives in the Chicago area with his wife, Anne Reuland, an academic administrator at Loyola University.

Digital rights are those human rights and legal rights that allow individuals to access, use, create, and publish digital media or to access and use computers, other electronic devices, and telecommunications networks. The concept is particularly related to the protection and realization of existing rights, such as the right to privacy and freedom of expression, in the context of digital technologies, especially the Internet. The laws of several countries recognize a right to Internet access.

Judith Fingeret Krug was an American librarian, freedom of speech proponent, and critic of censorship. Krug became director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom at the American Library Association in 1967. In 1969, she joined the Freedom to Read Foundation as its executive director. Krug co-founded Banned Books Week in 1982.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to library and information science:

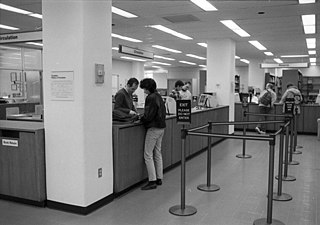

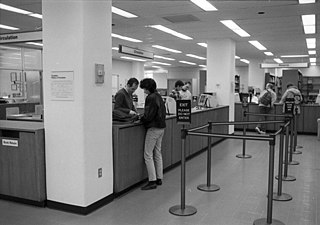

Library circulation or library lending comprises the activities around the lending of library books and other material to users of a lending library. A circulation or lending department is one of the key departments of a library.

A public computer is any of various computers available in public areas. Some places where public computers may be available are libraries, schools, or dedicated facilities run by government.

Banned Books Week is an annual awareness campaign promoted by the American Library Association and Amnesty International, that celebrates the freedom to read, draws attention to banned and challenged books, and highlights persecuted individuals. Held in late September or early October since 1982, the United States campaign "stresses the importance of ensuring the availability of those unorthodox or unpopular viewpoints to all who wish to read them" and the requirement to keep material publicly available so that people can develop their own conclusions and opinions. The international campaign notes individuals "persecuted because of the writings that they produce, circulate or read." Some of the events that occur during Banned Book Week are The Virtual Read-Out and The First Amendment Film Festival.

Forrest Brisbin Spaulding was an American librarian. He was named in the American Libraries article, "100 of the most important leaders we had in the 20th century" for his contribution to intellectual freedom in writing the Library Bill of Rights. He was a humanitarian who is remembered not only for his contributions to librarianship, but also for the positive influence he had on the communities in which he lived and worked. In a commentary on the play The Not So Quiet Librarian, by Cynthia Mercati, Humanities Iowa writes that "Spaulding's words and his life touched everyone who loved not just books but freedom of expression." While Forrest Spaulding is remembered for his contributions to librarianship, he began his career as a reporter. The State Library of Iowa biography mentions that while he spent some time as director of Peru's libraries and museums in 1920, "he was also a correspondent for the Associated Press. He is noted as saying that his 'efforts to report the news from that country gave him a bitter object lesson in censorship.'"

The New Jersey Library Association (NJLA) is a library organization located in Bordentown, New Jersey. It was established in 1890, and is the oldest library organization in the State of New Jersey. The NJLA began in 1890 with 39 members, and currently has over 1,700. The organization states on its website that it "advocates for the advancement of library services for the residents of New Jersey, provides continuing education & networking opportunities for librarians", and "supports the principles of intellectual freedom & promotes access to library materials for all".

Everett Thomson Moore was a Harvard University-educated librarian active in the Freedom to Read Foundation, which promoted intellectual freedom in libraries. He worked as an academic librarian at the University of Illinois, University of California, Berkeley, and University of California, Los Angeles, eventually joining UCLA's School of Library Service faculty in 1961. Moore is most famous for challenging California's attorney general on issues of censorship and intellectual freedom in libraries in the case of Moore v. Younger. In 1999, American Libraries named him one of the "100 Most Important Leaders We Had in the 20th Century".

Ralph Adrian Ulveling was an American librarian best known for his support of intellectual freedom, interracial understanding, and the advancement of the library and information science profession. He is listed as one of the most important contributors to the library profession during the 20th century by the journal American Libraries.

William Shepherd Dix was a scholar and librarian who had a 22-year career as Librarian at Princeton University in New Jersey, without a degree in library science. His contributions to the field of librarianship, however, are varied and notable, making him worthy of recognition in the American Libraries' 100 most important figures.

Clara Stanton Jones was the first African-American president of the American Library Association, serving as its acting president from April 11 to July 22 in 1976 and then its president from July 22, 1976, to 1977. Also, in 1970 she became the first African American and the first woman to serve as director of a major library system in America, as director of the Detroit Public Library.

Emerson Greenaway was an American librarian of considerable note, particularly during the Cold War era of the 1950s. During his long career, he acted as the director of the Enoch Pratt Free Library of Baltimore, the director of the Free Library of Philadelphia and president of the American Library Association. He was also a highly respected scholar and an advocate for intellectual freedom in wartime. Greenaway also came under fire for his participation in anti-communist government committees. In 1999, American Libraries named Greenaway as one of the one hundred most important library figures of the 20th century.

Intellectual freedom encompasses the freedom to hold, receive and disseminate ideas without restriction. Viewed as an integral component of a democratic society, intellectual freedom protects an individual's right to access, explore, consider, and express ideas and information as the basis for a self-governing, well-informed citizenry. Intellectual freedom comprises the bedrock for freedoms of expression, speech, and the press and relates to freedoms of information and the right to privacy.

Librarianship and human rights in the U.S. are linked by the philosophy and practice of library and information professionals supporting the rights enumerated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), particularly the established rights to information, knowledge and free expression.

Book censorship is the removal, suppression, or restricted circulation of literary, artistic, or educational material on the grounds that it is morally or otherwise objectionable according to the standards applied by the censor. The first instance of book censorship in what is now known as the United States, took place in 1637 in modern-day Quincy, Massachusetts. While specific titles caused bouts of book censorship, with Uncle Tom’s Cabin frequently cited as the first book subject to a national ban, censorship of reading materials and their distribution remained sporadic in the United States until the Comstock Laws in 1873. It was in the early 20th century that book censorship became a more common practice and source of public debate. Throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries there have been waves of attempts at widespread book censorship in the US. Since 2022, the country has seen a dramatic increase of attempted and successful censorship, with a 63% rise in reported cases between 2022 and 2023, including a substantial rise in challenges filed to hundreds of books at a time. In recent years, about three-fourths of books subject to censorship in the US are for children, pre-teenagers, and teenagers.

The International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance is a document officially launched at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva in September 2013 by the Electronic Frontier Foundation which attempts to "clarify how international human rights law applies in the current digital environment". Communications surveillance conflicts with a number of international human rights, mainly that of privacy. As a result, communications surveillance may only occur when prescribed by law necessary to achieve legitimate aim, and proportionate to the aim used.

The Freedom to Read Foundation (FTRF) is an American non-profit anti-censorship organization, established in 1969 by the American Library Association. The organization has been active in First Amendment-based challenges to book removals from libraries, and in anti-surveillance work. In addition to its legal work, the FTRF engages in advocacy and public awareness, such as its sponsorship of the annual celebration of "Banned Books Week".