In cell biology, a vesicle is a structure within or outside a cell, consisting of liquid or cytoplasm enclosed by a lipid bilayer. Vesicles form naturally during the processes of secretion (exocytosis), uptake (endocytosis), and the transport of materials within the plasma membrane. Alternatively, they may be prepared artificially, in which case they are called liposomes. If there is only one phospholipid bilayer, the vesicles are called unilamellar liposomes; otherwise they are called multilamellar liposomes. The membrane enclosing the vesicle is also a lamellar phase, similar to that of the plasma membrane, and intracellular vesicles can fuse with the plasma membrane to release their contents outside the cell. Vesicles can also fuse with other organelles within the cell. A vesicle released from the cell is known as an extracellular vesicle.

Exocytosis is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules out of the cell. As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use of energy to transport material. Exocytosis and its counterpart, endocytosis, are used by all cells because most chemical substances important to them are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the hydrophobic portion of the cell membrane by passive means. Exocytosis is the process by which a large amount of molecules are released; thus it is a form of bulk transport. Exocytosis occurs via secretory portals at the cell plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structure at the cell plasma membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

Pardaxin is a peptide produced by the Red Sea sole and the Pacific Peacock sole that is used as a shark repellent. It causes lysis of mammalian and bacterial cells, similar to melittin.

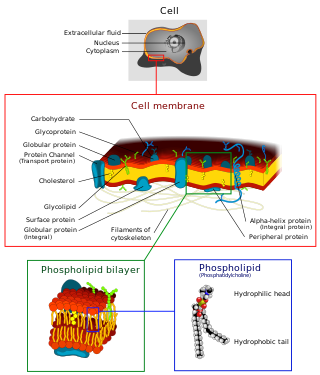

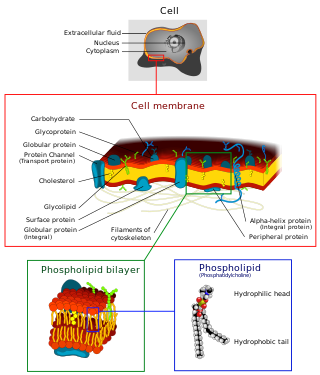

The lipid bilayer is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus, and membranes of the membrane-bound organelles in the cell. The lipid bilayer is the barrier that keeps ions, proteins and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be. Lipid bilayers are ideally suited to this role, even though they are only a few nanometers in width, because they are impermeable to most water-soluble (hydrophilic) molecules. Bilayers are particularly impermeable to ions, which allows cells to regulate salt concentrations and pH by transporting ions across their membranes using proteins called ion pumps.

A liposome is a small artificial vesicle, spherical in shape, having at least one lipid bilayer. Due to their hydrophobicity and/or hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, particle size and many other properties, liposomes can be used as drug delivery vehicles for administration of pharmaceutical drugs and nutrients, such as lipid nanoparticles in mRNA vaccines, and DNA vaccines. Liposomes can be prepared by disrupting biological membranes.

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles store various neurotransmitters that are released at the synapse. The release is regulated by a voltage-dependent calcium channel. Vesicles are essential for propagating nerve impulses between neurons and are constantly recreated by the cell. The area in the axon that holds groups of vesicles is an axon terminal or "terminal bouton". Up to 130 vesicles can be released per bouton over a ten-minute period of stimulation at 0.2 Hz. In the visual cortex of the human brain, synaptic vesicles have an average diameter of 39.5 nanometers (nm) with a standard deviation of 5.1 nm.

Phosphatidic acids are anionic phospholipids important to cell signaling and direct activation of lipid-gated ion channels. Hydrolysis of phosphatidic acid gives rise to one molecule each of glycerol and phosphoric acid and two molecules of fatty acids. They constitute about 0.25% of phospholipids in the bilayer.

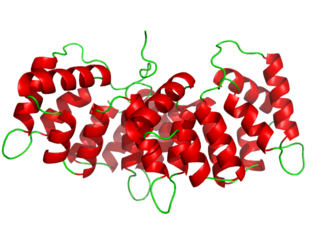

Annexin is a common name for a group of cellular proteins. They are mostly found in eukaryotic organisms.

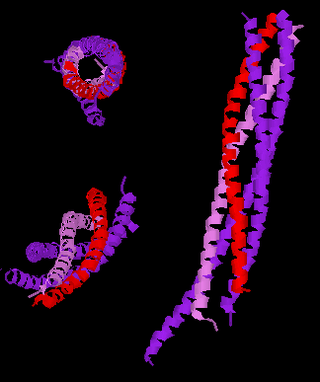

SNARE proteins – "SNAPREceptors" – are a large protein family consisting of at least 24 members in yeasts, more than 60 members in mammalian cells, and some numbers in plants. The primary role of SNARE proteins is to mediate the fusion of vesicles with the target membrane; this notably mediates exocytosis, but can also mediate the fusion of vesicles with membrane-bound compartments. The best studied SNAREs are those that mediate the release of synaptic vesicles containing neurotransmitters in neurons. These neuronal SNAREs are the targets of the neurotoxins responsible for botulism and tetanus produced by certain bacteria.

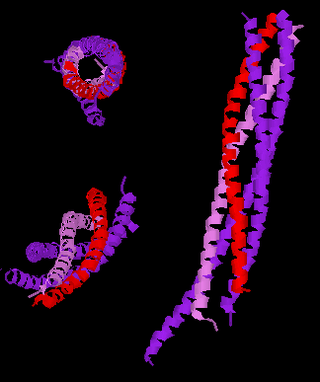

Synaptobrevins are small integral membrane proteins of secretory vesicles with molecular weight of 18 kilodalton (kDa) that are part of the vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP) family.

Cationic liposomes are spherical structures that contain positively charged lipids. Cationic liposomes can vary in size between 40 nm and 500 nm, and they can either have one lipid bilayer (monolamellar) or multiple lipid bilayers (multilamellar). The positive charge of the phospholipids allows cationic liposomes to form complexes with negatively charged nucleic acids through ionic interactions. Upon interacting with nucleic acids, cationic liposomes form clusters of aggregated vesicles. These interactions allow cationic liposomes to condense and encapsulate various therapeutic and diagnostic agents in their aqueous compartment or in their lipid bilayer. These cationic liposome-nucleic acid complexes are also referred to as lipoplexes. Due to the overall positive charge of cationic liposomes, they interact with negatively charged cell membranes more readily than classic liposomes. This positive charge can also create some issues in vivo, such as binding to plasma proteins in the bloodstream, which leads to opsonization. These issues can be reduced by optimizing the physical and chemical properties of cationic liposomes through their lipid composition. Cationic liposomes are increasingly being researched for use as delivery vectors in gene therapy due to their capability to efficiently transfect cells. A common application for cationic liposomes is cancer drug delivery.

Calcein, also known as fluorexon, fluorescein complex, is a fluorescent dye with excitation and emission wavelengths of 495 and 515 nm, respectively, and has the appearance of orange crystals. Calcein self-quenches at concentrations above 70 mM and is commonly used as an indicator of lipid vesicle leakage. It has also been traditionally used as a complexometric indicator for titration of calcium ions with EDTA, and for fluorometric determination of calcium.

Syntaxin-6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the STX6 gene.

Protein–lipid interaction is the influence of membrane proteins on the lipid physical state or vice versa.

Axon terminals are distal terminations of the branches of an axon. An axon, also called a nerve fiber, is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell that conducts electrical impulses called action potentials away from the neuron's cell body in order to transmit those impulses to other neurons, muscle cells or glands. In the central nervous system, most presynaptic terminals are actually formed along the axons, not at their ends.

A model lipid bilayer is any bilayer assembled in vitro, as opposed to the bilayer of natural cell membranes or covering various sub-cellular structures like the nucleus. They are used to study the fundamental properties of biological membranes in a simplified and well-controlled environment, and increasingly in bottom-up synthetic biology for the construction of artificial cells. A model bilayer can be made with either synthetic or natural lipids. The simplest model systems contain only a single pure synthetic lipid. More physiologically relevant model bilayers can be made with mixtures of several synthetic or natural lipids.

Vesicle fusion is the merging of a vesicle with other vesicles or a part of a cell membrane. In the latter case, it is the end stage of secretion from secretory vesicles, where their contents are expelled from the cell through exocytosis. Vesicles can also fuse with other target cell compartments, such as a lysosome. Exocytosis occurs when secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse at the base of cup-shaped structures at the cell plasma membrane called porosome, the universal secretory machinery in cells. Vesicle fusion may depend on SNARE proteins in the presence of increased intracellular calcium (Ca2+) concentration.

The cell membrane is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose. The cell membrane controls the movement of substances in and out of a cell, being selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules. In addition, cell membranes are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, ion conductivity, and cell signalling and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures, including the cell wall and the carbohydrate layer called the glycocalyx, as well as the intracellular network of protein fibers called the cytoskeleton. In the field of synthetic biology, cell membranes can be artificially reassembled.

Membrane vesicle trafficking in eukaryotic animal cells involves movement of biochemical signal molecules from synthesis-and-packaging locations in the Golgi body to specific release locations on the inside of the plasma membrane of the secretory cell. It takes place in the form of Golgi membrane-bound micro-sized vesicles, termed membrane vesicles (MVs).

A unilamellar liposome is a spherical liposome, a vesicle, bounded by a single bilayer of an amphiphilic lipid or a mixture of such lipids, containing aqueous solution inside the chamber. Unilamellar liposomes are used to study biological systems and to mimic cell membranes, and are classified into three groups based on their size: small unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (SUVs) that with a size range of 20–100 nm, large unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (LUVs) with a size range of 100–1000 nm and giant unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (GUVs) with a size range of 1–200 µm. GUVs are mostly used as models for biological membranes in research work. Animal cells are 10–30 µm and plant cells are typically 10–100 µm. Even smaller cell organelles such as mitochondria are typically 1–2 µm. Therefore, a proper model should account for the size of the specimen being studied. In addition, the size of vesicles dictates their membrane curvature which is an important factor in studying fusion proteins. SUVs have a higher membrane curvature and vesicles with high membrane curvature can promote membrane fusion faster than vesicles with lower membrane curvature such as GUVs.