The Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE), sometimes called the Church of the East and officially known as the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East (HACACE), is an Eastern Christian church that follows the traditional Christology and ecclesiology of the historical Church of the East. It belongs to the eastern branch of Syriac Christianity, and employs the Divine Liturgy of Saints Addai and Mari belonging to the East Syriac Rite. Its main liturgical language is Classical Syriac, a dialect of Eastern Aramaic, and the majority of its adherents are ethnic Assyrians.

Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa was the first Patriarch of what was to become the Shemʿon line of Chaldean Catholic Church, from 1553 to 1555, after it absorbed this Church of the East patriarchate into full communion with the Holy See and the Catholic Church.

The Metropolitanate of Maishan or Maysan was an East Syriac metropolitan province of the Church of the East between the fifth and thirteenth centuries. The historical region of Maishan or Maysan is situated in southern Iran. The metropolitans of Maishan sat at Prath d'Maishan, and for most of its history the province had three suffragan dioceses, at Karka d'Maishan, Rima and Nahargur. The last metropolitan of Maishan, the noted East Syriac author Shlemun (Solomon) of Basra, is attested in 1222, and it is not clear when the province ceased to exist.

The Patriarchal Province of Seleucia-Ctesiphon was an ecclesiastical province of the Church of the East, with see in Seleucia-Ctesiphon. It was attested between the fifth and thirteenth centuries. As its name entails, it was the province of the patriarch of the Church of the East. The province consisted of a number of dioceses in the region of Beth Aramaye, between Basra and Kirkuk, which were placed under the patriarch's direct supervision at the synod of Yahballaha I in 420.

Beth Huzaye or ʿIlam was an East Syriac metropolitan province of the Church of the East, between the fifth and fourteenth centuries. The metropolitan bishops of Beth Huzaye sat at Beth Lapat (Jundishapur). The metropolitan province of Beth Huzaye had a number of suffragan dioceses at different periods in its history, including Karka d'Ledan, Hormizd Ardashir, Shushter, Susa, Ispahan, Mihraganqadaq and Ram Hormizd. The diocese of Shahpur Khwast may also have been a suffragan diocese of the province of Beth Huzaye.

For much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the district of Salmas in northwest Iran was an archdiocese of the Chaldean Catholic Church, now a part of the Chaldean Catholic Archeparchy of Urmyā.

Dioceses of the Church of the East after 1552 were dioceses of the Church of the East and its subsequent branches, both traditionalist and pro-Catholic.

Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of Amadiya was a historical eparchy (diocese) of the Chaldean Catholic Church, until it was united with the Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of Zakho in 2013.

Diocese of Berwari was an East Syriac diocese of the Church of the East, existing between the 16th and 20th centuries and covering the region of Berwari.

Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of Seert was a diocese of the Chaldean Catholic Church, centered in Seert. It existed during the eighteenth, nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The diocese was ruined during the First World War.

Mardin was a diocese of the Chaldean Church from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. The diocese lapsed in 1941. Prior to this, it was a diocese of the Assyrian Church of the East, from which the Chaldean Catholic Church originated.

The Church of the East or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian Church, was an Eastern Christian church of the East Syriac Rite, based in Mesopotamia. It was one of three major branches of Eastern Christianity that arose from the Christological controversies of the 5th and 6th centuries, alongside the Oriental Orthodox Churches and the Chalcedonian Church. During the early modern period, a series of schisms gave rise to rival patriarchates, sometimes two, sometimes three. Since the latter half of the 20th century, three churches in Iraq claim the heritage of the Church of the East. Meanwhile, the East Syriac churches in India claim the heritage of the Church of the East in India.

Diocese of Kashkar, sometimes called Kaskar, was the senior diocese in the Church of the East's Province of the Patriarch. It see was in the city of Kashkar. The diocese is attested between the fourth and the twelfth centuries. The bishops of Kashkar had the privilege of guarding the patriarchal throne during the interregnum between the death of a patriarch and the appointment of his successor. As a result, they are often mentioned by name in the standard histories of the Nestorian patriarchs, so that a relatively full list of the bishops of the diocese has survived.

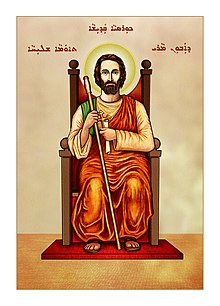

The patriarch of the Church of the East is the patriarch, or leader and head bishop of the Church of the East. The position dates to the early centuries of Christianity within the Sassanid Empire, and the Church has been known by a variety of names, including the Church of the East, Nestorian Church, the Persian Church, the Sassanid Church, or East Syrian.

Mar Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb, born Īshōʿyahb bar Māmā, was Patriarch of the Church of the East from 1539 to 1558, with residence in Rabban Hormizd Monastery.

Metropolitanate of India was an East Syriac ecclesiastical province of the Church of the East, at least nominally, from the seventh to the sixteenth century. The Malabar region (Kerala) of India had long been home to a thriving Eastern Christian community, known as the Saint Thomas Christians. The community traces its origins to the evangelical activity of Thomas the Apostle in the 1st century. The Christian communities in India used the East Syriac Rite, the traditional liturgical rite of the Church of the East. They also adopted some aspects of Dyophysitism of Theodore of Mopsuestia, often inaccurately referred as Nestorianism, in accordance with theology of the Church of the East. It is unclear when the relation between Saint Thomas Christian and the Church of the East was established. Initially, they belonged to the metropolitan province of Fars, but were detached from that province in the 7th century, and again in the 8th, and given their own metropolitan bishop.

Shimun, also transliterated as Shemʿon or Shimon is the form of Simon used in Classical Syriac and other Aramaic languages.

Mar Shimun XVI Yohannan was Patriarch of the Shem'on line (Qodshanis) of the Church of the East, from 1780. In 1804, he became the sole Patriarch among traditionalist Christians of the East Syriac Rite, because the rival Patriarch Eliya XII (1778-1804) of the Eliya line died without successor. Shimun XVI remained patriarch until his death in 1820.

Eliya XII was Patriarch of the Church of the East, from 1778 to 1804, with formal residence in Rabban Hormizd Monastery, near Alqosh, in modern Iraq. His birth name was Ishoyahb, and he was the elder son of priest Abraham, who was brother of the previous patriarch Eliya XI (1722-1778). In 1744, Ishoyahb was consecrated as metropolitan, and designated as presumptive successor by his paternal uncle, patriarch Eliya XI, who died in 1778, and Ishoyahb succeeded him, as patriarch Eliya XII. His tenure was marked by a prolonged rivalry with his pro-Catholic cousin Yohannan Hormizd, who also claimed the patriarchal throne. In 1804, Eliya XII died and was buried in the Rabban Hormizd Monastery, as the last patriarch of the senior Eliya line.