The word lituus originally meant a curved augural staff, or a curved war-trumpet in the ancient Latin language. This Latin word continued in use through the 18th century as an alternative to the vernacular names of various musical instruments.

The word lituus originally meant a curved augural staff, or a curved war-trumpet in the ancient Latin language. This Latin word continued in use through the 18th century as an alternative to the vernacular names of various musical instruments.

The lituus was a crooked wand (similar in shape to the top part of some Western European crosiers) used as a cult instrument in ancient Roman religion by augurs [1] to mark out a ritual space in the sky (a templum ). The passage of birds through this templum indicated divine favor or disfavor for a given undertaking.

The lituus was also used as a symbol of office for the college of the augurs to mark them out as a priestly group.

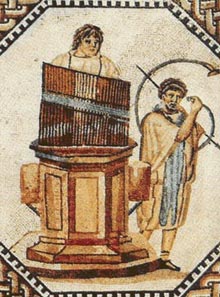

The ancient lituus was an Etruscan high-pitched brass instrument, which was straight but bent at the end, in the shape of a letter J, similar to the Gallic carnyx. It was later used by the Romans, especially for processional music and as a signalling horn in the army. For the Roman military it may have been particular to the cavalry, and both the Etruscan and Roman versions were always used in pairs, like the prehistoric lurer. Unlike the Roman litui, the Etruscan instruments had detachable mouthpieces and in general appear to have been longer. [2] The name lituus is Latin, thought to have been derived from an Etruscan cultic word describing a soothsayer's wand modelled on a shepherd's crook and associated with sacrifice and favourable omens. Earlier Roman and Etruscan depictions show the instrument used in processions, especially funeral processions. Players of the lituus were called liticines, though the name of the instrument appears to have been loosely used (by poets, not likely by soldiers) to describe other military brass instruments, such as the tuba or the buccina . [3] In 17th-century Germany a variant of the bent ancient lituus was still used as a signalling horn by nightwatchmen.[ citation needed ]

From the end of the 10th through the 13th centuries, chroniclers of the Crusades used the word lituus vaguely—along with the Classical Latin names for other Roman military Trumpets and horns, such as the tuba , cornu , and buccina and the more up-to-date French term trompe—to describe various instruments employed in the Christian armies. However, it is impossible to determine just what sort of instrument might have been meant, and it is unlikely their litui were the same as the Etrusco-Roman instrument. [4]

In the early 15th century, Jean de Gerson listed the lituus among those string instruments that were sounded by beating or striking, either with the fingernails, a plectrum, or a stick. Other instruments Gerson names in this category are the cythara , guiterna , psalterium , timpanum, and campanula. [5]

Throughout the postclassical era the name lituus continued to be used when discussing ancient and Biblical instruments, but with reference to contemporary musical practice in the Renaissance it usually referred to "bent horns" made of wood, particularly the crumhorn and the cornett. [6] The crumhorn was especially associated with the lituus because of the similarity of its shape. The equation of the crumhorn with the lituus was especially strong among German writers. [7] A 1585 English translation of Hadrianus Junius's Nomenclator defines lituus as "a writhen or crooked trumpet winding in and out; a shaulme" (i.e., shawm), but a polyglot edition of the same book published in 1606 demonstrates how differently the term might have been understood in various languages at that time: German Schalmey, Krumme Trommeten, Krumhorn; Dutch Schalmeye; French Claron, ou cleron; Italian Trombetta bastarda; Spanish Trompeta curua, ò bastarda. [8] The early Baroque composer and author Michael Praetorius used the word as a Latin equivalent of the German "Schallmeye" (shawm) or for the "Krumbhoerner" (crumhorns)—in the latter case also offering the Italian translations storti, and cornamuti torti. [9]

A more particular term, lituus alpinus, was used in 1555 by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner when he published the earliest detailed description of the Alphorn: "nearly eleven feet long, made from two pieces of wood slightly curved and hollowed out, fitted together and skillfully bound with osiers". [10]

A study made of Swedish dictionaries found that during the seventeenth century lituus was variously translated as sinka (= German Zink, cornett), krumhorn, krum trometa (curved trumpet), claret , or horn. [11]

In the eighteenth century the word once again came to describe contemporary brass instruments, such as in a 1706 inventory from the Ossegg monastery in Bohemia, which equates it with the hunting horn: "litui vulgo Waldhörner duo ex tono G". [12] Nevertheless, in 1732 Johann Gottfried Walther referred back to Renaissance and Medieval definitions, defining lituus as "a cornett, formerly it also signified a shawm or, in Italian tubam curvam, a HeerHorn". [13] (Heerhorn or Herhorn was a Middle High German name for a metal, slightly curved military signal horn, approximately five feet long, played with the bell turned upward.) [14] In 1738, the well-known horn player Anton Joseph Hampel served as a godfather at the baptism of a daughter of the renowned Dresden lutenist Silvius Leopold Weiss. In the baptismal register he was described as "Lituista Regius"—"royal lituus player". [15] In the second half of the 18th century the lituus was described in one source as a Latin name for the trumpet or horn. [16]

A number of musical compositions from the Baroque era specify an instrument by the Latin name lituus, including Bach's motet O Jesu Christ, meins Lebens Licht (BWV 118), a partita attributed to Jan Josef Ignác Brentner, as well as several masses and concertos by Johann Valentin Rathgeber. Scientists from Edinburgh University tried to recreate the lituus used by Bach in May 2009, in the form of a long wooden trumpet, assuming the word did not refer to a modern horn but to an instrument that had been out of use for 300 years. [17] [18]

The alphorn or alpenhorn or alpine horn is a labrophone, consisting of a straight several-meter-long wooden natural horn of conical bore, with a wooden cup-shaped mouthpiece. Traditionally the Alphorn was made of one single piece, or two parts at most, of the wood of a red pine tree. Sometimes the trees would bend from the weight of snow in winter, and this caused them to have the larger and bent mouthpiece at their ends. Modern Alphorns are sometimes made from three distinct parts that can be attached together: this is to make them easier to transport by car, or even to carry them by hand, and today they are more frequently made from the wood of a spruce tree or fir tree. The alphorn is used by mountain dwellers in the Swiss Alps. Similar wooden horns were used for communication in most mountainous regions of Europe, from the Alps to the Carpathians. Alphorns are today used as musical instruments.

The cornet is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B♭. There is also a soprano cornet in E♭ and cornets in A and C. All are unrelated to the Renaissance and early Baroque cornett.

The cornett, cornetto, or zink is a wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650.

The bugle is a simple signaling brass instrument with a wide conical bore. It normally has no valves or other pitch-altering devices, and is thus limited to its natural harmonic notes, and pitch is controlled entirely by varying the air and embouchure.

The shawm is a conical bore, double-reed woodwind instrument made in Europe from the 12th century to the present day. It achieved its peak of popularity during the medieval and Renaissance periods, after which it was gradually eclipsed by the oboe family of descendant instruments in classical music. It is likely to have come to Western Europe from the Eastern Mediterranean around the time of the Crusades. Double-reed instruments similar to the shawm were long present in Southern Europe and the East, for instance the ancient Greek, and later Byzantine aulos, the closely related sorna and zurna, and the Armenian duduk.

Sinfonia is the Italian word for symphony, from the Latin symphonia, in turn derived from Ancient Greek συμφωνία symphōnia, from the prefix σύν (together) and ϕωνή (sound). In English it most commonly refers to a 17th- or 18th-century orchestral piece used as an introduction, interlude, or postlude to an opera, oratorio, cantata, or suite. The word is also found in other Romance languages such as Spanish or Portuguese.

A cornu or 'a'cornum was an ancient Roman brass instrument about 3 m (9.8 ft) long in the shape of a letter 'G'. The instrument was braced by a crossbar that stiffened the structure and provided a means of supporting its weight on the player's shoulder. Some specimens survive in the archaeological record, two from the ruins of Pompeii.

The timbrel or tabret was the principal percussion instrument of the ancient Israelites. It resembled either a frame drum or a modern tambourine.

The Roman tuba, or trumpet was a military signal instrument used by the ancient Roman military and in religious rituals. They would signal troop movements such as retreating, attacking, or charging, as well as when guards should mount, sleep, or change posts. Thirty-six or thirty-eight tubicines were assigned to each Roman legion. The tuba would be blown twice each spring in military, governmental, or religious functions. This ceremony was known as the tubilustrium. It was also used in ancient Roman triumphs. It was considered a symbol of war and battle. The instrument was used by the Etruscans in their funerary rituals. It continued to be used in ancient Roman funerary practices.

In music, the bore of a wind instrument is its interior chamber. This defines a flow path through which air travels, which is set into vibration to produce sounds. The shape of the bore has a strong influence on the instrument's timbre.

Clarion is a name for a high-pitched trumpet used in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It is also a name for a 4' organ reed stop that produces a high-pitched or clarion-like sound on a pipe organ in the clarion trumpet's range of notes.

Zuffolo (also chiufolo, ciufolo) is an Italian fipple flute. First described in the 14th century, it has a rear thumb-hole, two front finger-holes, and a conical bore. It is approximately 8 cm in length and has a range of over two octaves, from B3 to C6 (Marcuse 1975c). A larger instrument of the same name, with a lowest note of C5 appeared in the early 17th century (Fuller-Maitland, Baines, and Térey-Smith 2001).

The sornā or sornāy is an ancient Iranian woodwind instrument.

The chromatic trumpet of Western tradition is a fairly recent invention, but primitive trumpets of one form or another have been in existence for millennia; some of the predecessors of the modern instrument are now known to date back to the Neolithic era. The earliest of these primordial trumpets were adapted from animal horns and sea shells, and were common throughout Europe, Africa, India and, to a lesser extent, the Middle East. Primitive trumpets eventually found their way to most parts of the globe, though even today indigenous varieties are quite rare in the Americas, the Far East and South-East Asia. Some species of primitive trumpets can still be found in remote places, where they have remained largely untouched by the passage of time.

An aeneator was a specialized player of wind instruments who was attached to a Roman military unit. The word comes from Latin aēneus or ahēneus, "brazen", from aes, "copper alloy". While the size of individual Roman military units may have varied, they made extensive use of both acoustical and visual signaling in communications and each had an assigned banner bearer (vexillarius) and at least one aeneator. A variety of instruments were used by aeneatores, including the buccina, cornu, tuba, and lituus. In addition to their roles in the Roman army, aeneatores were also used for processionals and games, particularly in marching home from war.

The medieval lituus was a musical instrument of an indeterminate nature, known only from records which ascribe it various properties. Johann Sebastian Bach's O Jesu Christ, Meins Lebens Licht contains the only known piece of music written for an instrument under this name.

Deductions about the music of the ancient Celts of the La Tène period and their Gallo-Roman and Romano-British descendants of Late Antiquity rely primarily on Greek and Roman sources, as well as on archaeological finds and interpretations including the reconstruction of the Celts' ancient instruments. Most of the textual information centers on military conflicts and on maybe the most prominent Celtic instrument of its time, the carnyx.

A horn is any of a family of musical instruments made of a tube, usually made of metal and often curved in various ways, with one narrow end into which the musician blows, and a wide end from which sound emerges. In horns, unlike some other brass instruments such as the trumpet, the bore gradually increases in width through most of its length—that is to say, it is conical rather than cylindrical. In jazz and popular-music contexts, the word may be used loosely to refer to any wind instrument, and a section of brass or woodwind instruments, or a mixture of the two, is called a horn section in these contexts.

Nafir, also nfīr, plural anfār, Turkish nefir, is a slender shrill-sounding straight natural trumpet with a cylindrical tube and a conical metal bell, producing one or two notes. It was used as a military signaling instrument and as a ceremonial instrument in countries shaped by Islamic culture in North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. In Ottoman, Persian and Mugulin miniatures, the nafīr is depicted in battle scenes. In Christian culture, it displaced or was played alongside of the curved tuba or horn, as seen in artwork of about the 14th century A.D.