Related Research Articles

Karl-Theodor Maria Nikolaus Johann Jacob Philipp Franz Joseph Sylvester Buhl-Freiherr von und zu Guttenberg, known professionally as Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, is a German businessman and politician of the Christian Social Union (CSU). He served as a member of the Bundestag from 2002 to 2011, as Secretary-General of the CSU from 2008 to 2009, as Federal Minister for Economics and Technology in 2009 and as Federal Minister of Defence from 2009 to 2011.

Karl Theodor Maria Georg Achaz Eberhardt Josef Freiherr von und zu Guttenberg was a German politician of the Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU). He was parliamentary secretary of state in the Chancellor's Office in the government of Kurt Georg Kiesinger from 1967 until 1969, as well as the foreign policy spokesman of the CDU/CSU group in the Bundestag. Guttenberg was perceived as a hardline conservative anticommunist as well as a convinced proponent of European integration. His work was mostly within the field of foreign policy.

Thomas Bareiß is a German politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who has been serving as a member of the German Bundestag since 2005. From 2018 to 2021, he held the position of Parliamentary State Secretary at the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy in Chancellor Angela Merkel's cabinet.

Atlantik-Brücke is a leading private non-profit association to promote German-American understanding and Atlanticism. Founded in Hamburg in 1952, it was located in Bonn between 1983 and 1999 and is now located in Berlin.

The Memorandum of Tübingen was a memorandum dealing with West German foreign policy, written by eight prominent German Protestant academics and scientists. It was sent to the German Bundestag in 1961. The memorandum was a manifesto in protest of the planned nuclear armament of West Germany and in favour of the recognition of the Oder-Neiße line as the official border between Germany and Poland by the West German government. Both issues were highly controversial and hotly debated issues in West German politics at the time.

A Lobby Registry, also named Lobbyist Registry, Register for Lobby Transparency or Registry of Lobbyists is a public database, in which information about lobbying actors and key data about their actions can be accessed.

Dagmar Enkelmann is a German politician of Die Linke party.

Gabriele Gottwald is a German politician, and currently (2019) a member of the Berlin state parliament (Abgeordnetenhaus). Before reunification she served between 1983 and 1985 as a member of the West German Bundestag , at that time representing the Green Party. The 1983 election was the first at which Green Party members were elected to the Bundestag. On her first day at the Bundestag she arrived on her bicycle and caused the janitor consternation by insisting on bringing it through the security gate because she was concerned that if she left it outside it might be stolen.

Philipp Amthor is a German politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who has been a member of the Bundestag since the 2017 German federal election. From 2018 to 2020, he worked as a lobbyist for the now inactive IT-company Augustus Intelligence.

Anke Domscheit-Berg is a German politician and activist. She has been a member of the Bundestag since 2017, when she was elected on the party list of The Left, without being a party member. She joined the party in 2021 following her nomination to the top female position on the party election list in the state of Brandenburg. Previously, she was a member of the Pirate Party Germany and the Greens. She is married to Daniel Domscheit-Berg. In 2010 she received the Berliner Frauenpreis.

Olav Gutting is a German lawyer and politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who has been serving as a member of the Bundestag since 2002.

Marie-Luise Dött is a German politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who served as a member of the Bundestag from 1998 to 2021.

Florian Toncar is a German lawyer and politician of the Free Democratic Party (FDP) who has been serving as Parliamentary State Secretary in the Federal Ministry of Finance in the coalition government of Chancellor Olaf Scholz since 2021. He has served as a member of the Bundestag from the state of Baden-Württemberg from 2005 until 2013 and since 2017.

Danyal Bayaz is a German politician of Alliance 90/The Greens who has been serving as State Minister of Finance in the government of Minister-President of Baden-Württemberg Winfried Kretschmann since May 2021. From 2017 until 2021, he was a member of the Bundestag.

Nikolas Löbel is a German politician of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who served as a member of the Bundestag from the state of Baden-Württemberg from 2017 to 2021. He resigned in March 2021.

Karin Strenz was a German politician who represented the CDU. Strenz served as a member of the Bundestag for the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern between 2009 and 2021.

Dorothee Martin is a German politician for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) who has been serving as a member of the Bundestag since 2020, representing the Hamburg-Nord district.

The Foundation for Family Businesses is a non-profit foundation headquartered in Munich, Germany. It has a representative office in Berlin near the Reichstag building. Ever since the foundation was established in 2002, it has been committed to representing the interest of large family businesses Thus, it promotes academic research focusing on family businesses, in addition to holding events.

Michael Hartmann is a German politician and member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). He was a member of the German Bundestag from 2002 to 2017. Hartmann is a specialist politician for internal security and was the domestic policy spokesman of the SPD parliamentary group as well as the chairman of his parliamentary group in the Committee on Internal Affairs and a member of the Parliamentary Oversight Panel.

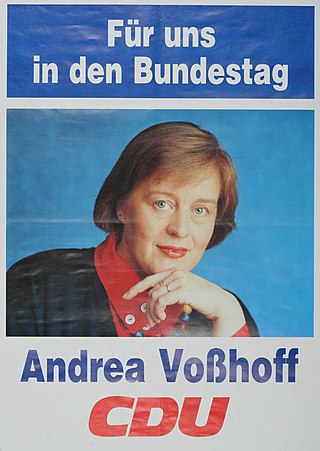

Andrea Voßhoff is a German former lawyer who switched to full-time politics in mid-career (CDU). She served as a member of the Bundestag between 1998 and 2013 when, as a "party list" candidate, she narrowly failed to secure re-election in the Brandenburg-Potsam electoral district.

References

- 1 2 "Neue Ethikregeln: Kabinett beschließt Verhaltenskodex für Lobbyisten" [New Ethics Rules: Cabinet Passes Code of Conduct for Lobbyists]. spiegel.de (in German). 16 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- 1 2 "Europarat bemängelt Deutschlands Kampf gegen Korruption" [Council of Europe Criticizes Germany's Fight Against Corruption]. Die Zeit (in German). 10 May 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ↑ "Informationen zum Dokument BVerfGE 5, 85 - KPD-Verbot". 17 August 1956. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

Es läßt sich nicht bezweifeln, daß außerparlamentarische Aktionen vielfältiger Art. denkbar sind, die einer legitimen Einwirkung auf das Parlament dienen können, vor allem soweit sie dazu bestimmt sind, die Abgeordneten über die bei den Wählern zu bestimmten politischen Fragen vorhandenen Meinungen zu unterrichten. An sich ist es daher verfassungsrechtlich nicht zu beanstanden, daß "Interessentengruppen" auf die Mitglieder des Parlaments einzuwirken suchen; auch Massenaktionen der Arbeiterschaft sind grundsätzlich nicht unzulässig.

- ↑ Amann, Melanie (26 January 2010). "Die spektakulären Erfolge der Solar-Lobby" [The Spectacular Successes of the Solar Lobby]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ↑ Watts, Jonathan (11 November 2020). "Five post-Trump obstacles to a global green recovery". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Balser, Markus; Ritzer, Uwe (29 February 2016). "Lobbyisten fliegen aus dem Bundestag - und bleiben genauso mächtig" [Lobbyists Banned from the Bundestag - and Remain just as Powerful]. Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). p. 17.

- ↑ Kamm, Raimund (9 January 2017). "Deutsche Emissionen stiegen 2016". klimaretter.info . Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ↑ Steffen, Tilman (11 May 2011). "Lobbyisten im Lehrerzimmer" [Lobbyists in the Teachers' Lounge]. Die Zeit (in German).

- 1 2 Denkler, Thorsten (27 January 2015). "So schützt der Bundestag Lobbyisten" [How the Bundestag Protects Lobbyists]. Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ↑ Schmedes, Hans-Jörg (2009). "Mehr Transparenz wagen? Zur Diskussion um ein gesetzliches Lobbyregister beim Deutschen Bundestag". Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen. 40 (3): 543–560. doi: 10.5771/0340-1758-2009-3-543 .

- ↑ Roßmann, Robert (8 June 2017). "Hausausweise: 706 Lobbyisten im Bundestag" [Access Badges: 706 Lobbyists in the Bundestag]. Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ↑ Arlt, Sophia; Wolf, Marcus (2020). "Ungleiches Terrain - Eine Studie zu Größe und Einfluss der Finanzlobby in Deutschland" (PDF). Bürgerbewegung Finanzwende. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- 1 2 "Bezahlte Lobbyisten in Bundesministerien: Wie die Regierung die Öffentlichkeit täuscht" [Paid Lobbyists in Federal Ministries: How the Government Deceives the Public]. Monitor Fernsehmagazin (in German). Westdeutscher Rundfunk. 15 December 2006.[ dead link ] Mirror on YouTube.

- ↑ Krempl, Stefan (27 July 2007). "Datenbank gibt Aufschluss über Lobbyisten in Ministerien". heise online . Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ↑ Gathmann, Florian; Weisensee, Nils (26 July 2007). "Lobbyisten-Liste enthüllt Einfluss in Ministerien" [Lobbyist-List Reveals Influence in Ministries]. Spiegel Online (in German).

- ↑ Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Volker Beck (Köln), Thea Dückert, Matthias Berninger , weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN (PDF). bundestag.de (Report). 4 December 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ↑ Schick, Nina (9 September 2015). "Zehn Jahre Atomausstieg – Meilenstein als Zerreißprobe". Focus Online .

- ↑ "Die strahlenden Sieger der Atomlobby. Die Laufzeitverlängerung für Atomkraftwerke ist ein großer Erfolg für die Energiekonzerne. Jetzt wollen sich andere Branchen diese Lobbyarbeit zum Vorbild nehmen" [Radiating with Success: The Nuclear Lobby. The Lifetime Extension is an Enormous Success for the Energy Industry. Now other Sectors want to copy its model]. Die Zeit (in German). 7 September 2010.

- ↑ Weigerle, Laura (21 June 2017). "Schwarz-Rot sieht rot" [Black-Red Sees Red]. Die Tageszeitung (in German).

- ↑ Bartz, Tim; Böcking, David; Hesse, Martin; Traufetter, Gerald (28 January 2021). "Wie Guttenberg mit Wirecard um Millionen feilschte" [How Guttenberg Haggled with Wirecard for Millions]. Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 25 June 2021.