Related Research Articles

Logical positivism, later called logical empiricism, and both of which together are also known as neopositivism, is a movement whose central thesis is the verification principle. This theory of knowledge asserts that only statements verifiable through direct observation or logical proof are meaningful in terms of conveying truth value, information or factual content. Starting in the late 1920s, groups of philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians formed the Berlin Circle and the Vienna Circle, which, in these two cities, would propound the ideas of logical positivism.

The mind is that which thinks, imagines, remembers, wills, and senses, or is the set of faculties responsible for such phenomena. The mind is also associated with experiencing perception, pleasure and pain, belief, desire, intention, and emotion. The mind can include conscious and non-conscious states as well as sensory and non-sensory experiences.

In philosophy, physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism—a "one substance" view of the nature of reality as opposed to a "two-substance" or "many-substance" (pluralism) view. Both the definition of "physical" and the meaning of physicalism have been debated.

In the philosophy of mind, functionalism is the thesis that each and every mental state is constituted solely by its functional role, which means its causal relation to other mental states, sensory inputs, and behavioral outputs. Functionalism developed largely as an alternative to the identity theory of mind and behaviorism.

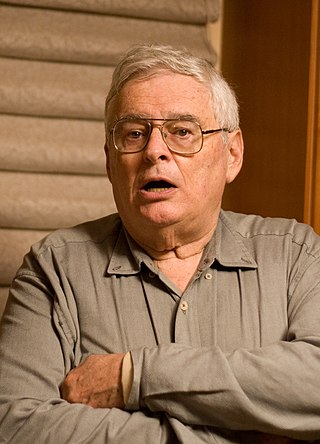

Jerry Alan Fodor was an American philosopher and the author of many crucial works in the fields of philosophy of mind and cognitive science. His writings in these fields laid the groundwork for the modularity of mind and the language of thought hypotheses, and he is recognized as having had "an enormous influence on virtually every portion of the philosophy of mind literature since 1960." At the time of his death in 2017, he held the position of State of New Jersey Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, at Rutgers University, and had taught previously at the City University of New York Graduate Center and MIT.

Behaviorism is a systematic approach to understand the behavior of humans and other animals. It assumes that behavior is either a reflex evoked by the pairing of certain antecedent stimuli in the environment, or a consequence of that individual's history, including especially reinforcement and punishment contingencies, together with the individual's current motivational state and controlling stimuli. Although behaviorists generally accept the important role of heredity in determining behavior, they focus primarily on environmental events. The cognitive revolution of the late 20th century largely replaced behaviorism as an explanatory theory with cognitive psychology, which unlike behaviorism examines internal mental states.

Gilbert Ryle was a British philosopher, principally known for his critique of Cartesian dualism, for which he coined the phrase "ghost in the machine." He was a representative of the generation of British ordinary language philosophers who shared Ludwig Wittgenstein's approach to philosophical problems.

In philosophy, Ryle's regress is a classic argument against cognitivist theories, and concludes that such theories are essentially meaningless as they do not explain what they purport to.

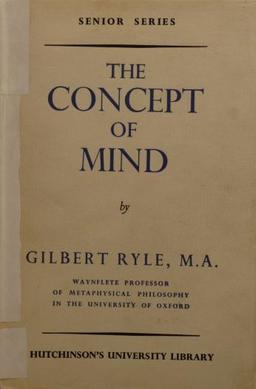

The Concept of Mind is a 1949 book by philosopher Gilbert Ryle, in which the author argues that "mind" is "a philosophical illusion hailing chiefly from René Descartes and sustained by logical errors and 'category mistakes' which have become habitual."

The Ghost in the Machine is a 1967 book about philosophical psychology by Arthur Koestler. The title is a phrase coined by the Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle to describe the Cartesian dualist account of the mind–body relationship. Koestler shares with Ryle the view that the mind of a person is not an independent non-material entity, temporarily inhabiting and governing the body. The work attempts to explain humanity's self-destructive tendency in terms of individual and collective functioning, philosophy, and overarching, cyclical political–historical dynamics, peaking in the nuclear weapons arena.

A mental state, or a mental property, is a state of mind of a person. Mental states comprise a diverse class, including perception, pain/pleasure experience, belief, desire, intention, emotion, and memory. There is controversy concerning the exact definition of the term. According to epistemic approaches, the essential mark of mental states is that their subject has privileged epistemic access while others can only infer their existence from outward signs. Consciousness-based approaches hold that all mental states are either conscious themselves or stand in the right relation to conscious states. Intentionality-based approaches, on the other hand, see the power of minds to refer to objects and represent the world as the mark of the mental. According to functionalist approaches, mental states are defined in terms of their role in the causal network independent of their intrinsic properties. Some philosophers deny all the aforementioned approaches by holding that the term "mental" refers to a cluster of loosely related ideas without an underlying unifying feature shared by all. Various overlapping classifications of mental states have been proposed. Important distinctions group mental phenomena together according to whether they are sensory, propositional, intentional, conscious or occurrent. Sensory states involve sense impressions like visual perceptions or bodily pains. Propositional attitudes, like beliefs and desires, are relations a subject has to a proposition. The characteristic of intentional states is that they refer to or are about objects or states of affairs. Conscious states are part of the phenomenal experience while occurrent states are causally efficacious within the owner's mind, with or without consciousness. An influential classification of mental states is due to Franz Brentano, who argues that there are only three basic kinds: presentations, judgments, and phenomena of love and hate.

Semantic holism is a theory in the philosophy of language to the effect that a certain part of language, be it a term or a complete sentence, can only be understood through its relations to a larger segment of language. There is substantial controversy, however, as to exactly what the larger segment of language in question consists of. In recent years, the debate surrounding semantic holism, which is one among the many forms of holism that are debated and discussed in contemporary philosophy, has tended to centre on the view that the "whole" in question consists of an entire language.

Type physicalism is a physicalist theory in the philosophy of mind. It asserts that mental events can be grouped into types, and can then be correlated with types of physical events in the brain. For example, one type of mental event, such as "mental pains" will, presumably, turn out to be describing one type of physical event.

A dog behaviourist is a person who works in modifying or changing behaviour in dogs. They can be experienced dog handlers, who have developed their experience over many years of hands-on experience, or have formal training up to degree level. Some have backgrounds in veterinary science, animal science, zoology, sociology, biology, or animal behaviour, and have applied their experience and knowledge to the interaction between humans and dogs. Professional certification may be offered through either industry associations or local educational institutions. There is however no compulsion for behaviourists to be a member of a professional body nor to take formal training.

Ullin Thomas Place, usually cited as U. T. Place, was a British philosopher and psychologist. Along with J. J. C. Smart, he developed the identity theory of mind. After several years at the University of Adelaide, he taught for some years in the Department of Philosophy in the University of Leeds.

The analytic–synthetic distinction is a semantic distinction used primarily in philosophy to distinguish between propositions that are of two types: analytic propositions and synthetic propositions. Analytic propositions are true or not true solely by virtue of their meaning, whereas synthetic propositions' truth, if any, derives from how their meaning relates to the world.

Anecdotal cognitivism is a method of research using anecdotal, and anthropomorphic evidence through the observation of animal behaviour.

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the body and the external world.

Functional psychology or functionalism refers to a psychological school of thought that was a direct outgrowth of Darwinian thinking which focuses attention on the utility and purpose of behavior that has been modified over years of human existence. Edward L. Thorndike, best known for his experiments with trial-and-error learning, came to be known as the leader of the loosely defined movement. This movement arose in the U.S. in the late 19th century in direct contrast to Edward Titchener's structuralism, which focused on the contents of consciousness rather than the motives and ideals of human behavior. Functionalism denies the principle of introspection, which tends to investigate the inner workings of human thinking rather than understanding the biological processes of the human consciousness.

"The Nature of Mind" is a philosophical essay by David Armstrong, originally published in The Nature of Mind and Other Essays in 1980. In this essay, Armstrong outlines a philosophical account of the mind that is compatible with the Materialist scientific view of the mind. He arrives at a theory of Central-State Materialism, a synthesis between Descartes' dualism and Gilbert Ryle's dispositional behaviourism.

References

- ↑ Alex Barber, Robert J Stainton (eds.), Concise Encyclopedia of Philosophy of Language and Linguistics, Elsevier, 2010, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Behaviorism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- ↑ Hempel, C. G. The Logical Analysis of psychology . 1935.

- ↑ Neil Tennant, Introducing Philosophy: God, Mind, World, and Logic, Routledge, 2015, p. 299.

- ↑ Graham, George. "Behaviorism". Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ↑ See Brains and Behavior, Hilary Putnam, 1968 (On the Purdue University website)