Sandra Cisneros is an American writer. She is best known for her first novel, The House on Mango Street (1983), and her subsequent short story collection, Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories (1991). Her work experiments with literary forms that investigate emerging subject positions, which Cisneros herself attributes to growing up in a context of cultural hybridity and economic inequality that endowed her with unique stories to tell. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, was awarded one of 25 new Ford Foundation Art of Change fellowships in 2017, and is regarded as a key figure in Chicano literature.

Cherríe Moraga is a Chicana feminist, writer, activist, poet, essayist, and playwright. She is part of the faculty at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the Department of English. Moraga is also a founding member of the social justice activist group La Red Chicana Indígena which is an organization of Chicanas fighting for education, culture rights, and Indigenous Rights.

Ana Castillo is a Chicana novelist, poet, short story writer, essayist, editor, playwright, translator and independent scholar. Considered one of the leading voices in Chicana experience, Castillo is most known for her experimental style as a Latina novelist and for her intervention in Chicana feminism known as Xicanisma.

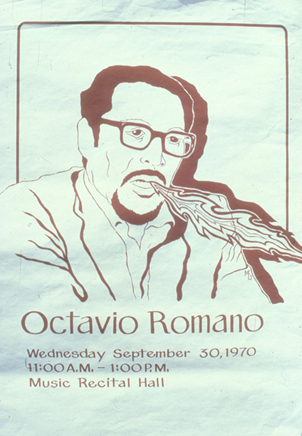

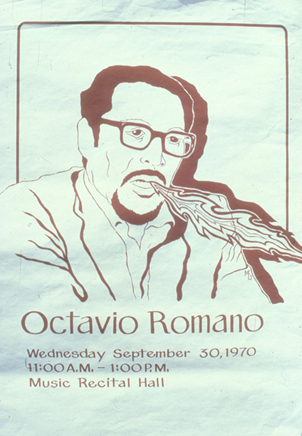

Quinto Sol was the first fully independent publishing house to surface from the Chicano movement in the Sixties. Editorial Quinto Sol was founded in 1967 at UC Berkeley by Octavio I. Romano, a Professor of Behavioral Science and Public Health, in collaboration with Nick C. Vaca and Andres Ybarra. The name "Quinto Sol" is Spanish for "Fifth Sun" and it refers to the Aztec myth of creation and destruction. Since the beginning of the Chicano movement in the 1960s, this concept has become a pathway to cultural expression. The Fifth Sun has constantly been integrated into the music, art and literature of the Chicano idea.

Norma Elia Cantú is a Chicana postmodernist writer and the Murchison Professor in the Humanities at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas.

José Antonio "Tony" Burciaga was an American Chicano artist, poet, and writer who explored issues of Chicano identity and American society.

Latino poetry is a branch of American poetry written by poets born or living in the United States who are of Latin American origin or descent and whose roots are tied to the Americas and their languages, cultures, and geography.

Chicano poetry is a subgenre of Chicano literature that stems from the cultural consciousness developed in the Chicano Movement. Chicano poetry has its roots in the reclamation of Chicana/o as an identity of empowerment rather than denigration. As a literary field, Chicano poetry emerged in the 1960s and formed its own independent literary current and voice.

Alicia Gaspar de Alba is an American scholar, cultural critic, novelist, and poet whose works include historical novels and scholarly studies on Chicana/o art, culture and sexuality.

Mexican American literature is literature written by Mexican Americans in the United States. Although its origins can be traced back to the sixteenth century, the bulk of Mexican American literature dates from post-1848 and the United States annexation of large parts of Mexico in the wake of the Mexican–American War. Today, as a part of American literature in general, this genre includes a vibrant and diverse set of narratives, prompting critics to describe it as providing "a new awareness of the historical and cultural independence of both northern and southern American hemispheres". Chicano literature is an aspect of Mexican American literature.

American literature written in Spanish in the United States dates back as 1610 when the Spanish explorer Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá published his epic poem Historia de Nuevo México. He was an early chronicler of the conquest of the Americas and a forerunner of Spanish-language literature in the United States given his focus on the American landscape and the customs of the people. However, it was not until the late 20th century that Spanish language literature written by Americans was regularly published in the United States.

Alma Luz Villanueva is an American poet, short story writer, and novelist.

Francisco Xavier Alarcón was a Chicano poet and educator. He was one of the few Chicano poets to have "gained recognition while writing mostly in Spanish" within the United States. His poems have been also translated into Irish and Swedish. He made many guest appearances at public schools so that he could help inspire and influence young people to write their own poetry especially because he felt that children are "natural poets."

Chicana literature is a form of literature that has emerged from the Chicana Feminist movement. It aims to redefine Chicana archetypes in an effort to provide positive models for Chicanas. Chicana writers redefine their relationships with what Gloria Anzaldúa has called "Las Tres Madres" of Mexican culture by depicting them as feminist sources of strength and compassion.

Latino literature is literature written by people of Latin American ancestry, often but not always in English, most notably by Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans, and Dominican Americans, many of whom were born in the United States. the origin of the term "Latino literature" dates back to the 1960s, during the Chicano Movement, which was a social and political movement by Mexican Americans seeking equal rights and representation. At the time, the term "Chicano literature" was used to describe the work of Mexican-American writers. As the movement expanded, the term "Latino" came into use to encompass writers of various Latin American backgrounds, including Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and others.

Emplumada is the first collection of poetry authored by Lorna Dee Cervantes. It was published in 1981 by University of Pittsburgh Press.

Carmen Tafolla is an internationally acclaimed Chicana writer from San Antonio, Texas, and a professor emerita of bicultural bilingual studies at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Tafolla served as the poet laureate of San Antonio from 2012 to 2014, and was named the Poet Laureate of Texas for 2015–16. Tafolla has written more than thirty books, and won multiple literary awards. She is one of the most highly anthologized Chicana authors in the United States, with her work appearing in more than 300 anthologies.

Demetria Martinez is an American activist, poet, and novelist.

Lucha Corpi is a Chicana poet and mystery writer. She was born on April 13, 1945 in Jaltipan, Veracruz, Mexico. In 1975 she earned a B.A. in comparative literature from the University of California, Berkeley. In 1979 she earned a M.A. in comparative literature from San Francisco State University. Corpi's most important contribution to Chicano literature, a series of four poems called "The Marina Poems ," appeared in the anthology The Other Voice: Twentieth-Century Women's Poetry in Translation, which was published by W. W. Norton & Company, in 1976 (ISBN 9780393044218).