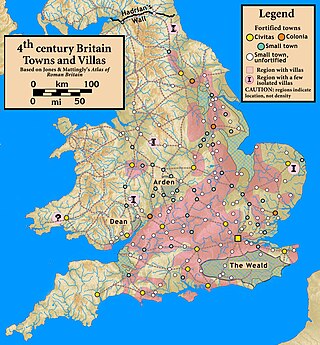

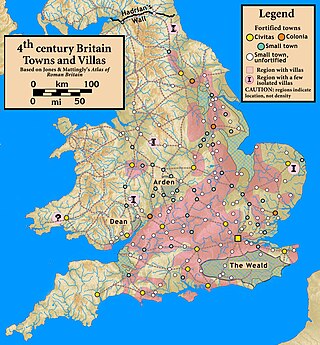

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman Province of Britannia after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Fishbourne Roman Palace is in the village of Fishbourne, Chichester in West Sussex. The palace is the largest Roman residence north of the Alps, and has an unusually early date of 75 AD, around thirty years after the Roman conquest of Britain.

Calleva Atrebatum was an Iron Age oppidum, the capital of the Atrebates tribe. It then became a walled town in the Roman province of Britannia, at a major crossroads of the roads of southern Britain.

Durnovaria is a suggested spelling for the Latin form of the name of the Roman town of Dorchester in the modern English county of Dorset, amended from the actually observed Durnonovaria. Upon the assumption that the name was originally Brythonic, it is suggested that the first element in the name, *durno- may mean "fist" like and the second may be related to Old Irish fáir ~ fóir denoting a confined area or den. A simpler amendment would lead to *Duronovaria, making this place one of up to 18 ancient British names that contain Duro- and mostly occur at river crossings, while -novaria has two possible ancient parallels in Britain associated with river junctions. That analysis would perfectly fit the geographical situation of Dorchester.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is an important Italian archaeological museum, particularly for ancient Roman remains. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites. From 1816 to 1861, it was known as Real Museo Borbonico.

Lullingstone is a village in the county of Kent, England. It is best known for its castle, Roman villa and its public golf course.

Hadrian's Villa is a UNESCO World Heritage Site comprising the ruins and archaeological remains of a large villa complex built around AD 120 by Roman Emperor Hadrian near Tivoli outside Rome.

The Villa Romana del Casale is a large and elaborate Roman villa or palace located about 3 km from the town of Piazza Armerina, Sicily. Excavations have revealed one of the richest, largest, and most varied collections of Roman mosaics in the world, for which the site has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The villa and artwork contained within date to the early 4th century AD.

Chedworth Roman Villa is located near Chedworth, Gloucestershire, England and is a scheduled monument. It is one of the largest and most elaborate Roman villas so far discovered in Britain and one with the latest occupation beyond the Roman period. The villa was built in phases from the early 2nd century to the 5th century, with the 4th-century construction transforming the building into an elite dwelling arranged around three sides of a courtyard. The 4th-century building included a heated and furnished west wing containing a dining-room (triclinium) with a fine mosaic floor, as well as two separate bathing suites: one for damp-heat and one for dry-heat.

Piddington Roman Villa is the remains of a large Roman villa at Piddington, Northamptonshire, about 6 miles (9.7 km) south-east of Northampton, a county in the East Midlands of England.

Great Witcombe Roman Villa was a villa built during the Roman occupation of Britain. It is located on a hillside at Great Witcombe, near Gloucester in the English county of Gloucestershire. It has been scheduled as an ancient monument.

Bignor Roman Villa is a large Roman courtyard villa which has been excavated and put on public display on the Bignor estate in the English county of West Sussex. It is well known for its high quality mosaic floors, which are some of the most complete and intricate in the country.

Brading Roman Villa was a Roman courtyard villa which has been excavated and put on public display in Brading on the Isle of Wight.

The Hinton St Mary Mosaic is a large, almost complete Roman mosaic discovered at Hinton St Mary, Dorset, England in 1963. It appears to feature a portrait bust of Jesus Christ as its central motif, which could be the oldest depiction of Jesus Christ anywhere in the Roman Empire. A second mosaic was found during 2022 excavations on the site. The mosaic found in 1963 was chosen as Object 44 in the BBC Radio 4 programme A History of the World in 100 Objects, presented by British Museum director Neil MacGregor.

Littlecote Roman Villa is an extensive and exceptional Roman villa, with associated religious complex, at Littlecote Park just over a mile west of Hungerford, Berkshire. It has been excavated and is on display to the public in the grounds of the estate.

Dalton Parlours Roman villa is a Roman villa and scheduled monument near Collingham, West Yorkshire.

Winterton Roman villa is a Roman villa in Winterton, North Lincolnshire. It was discovered in 1747.

Rudston Roman villa is a Roman villa and scheduled monument near Rudston, East Riding of Yorkshire.

Brantingham Roman villa is a Roman villa and scheduled monument near Brantingham, East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

The Rutland Roman villa is a Romano-British villa site in Rutland, England. The site was listed as a scheduled monument by Historic England on 23 November 2021. The villa includes the first example of a mosaic in Britain which depicts scenes from Homer's Iliad.