RMS Queen Elizabeth was an ocean liner operated by Cunard Line. In tandem with Queen Mary both ships provided a weekly luxury liner service between Southampton in the United Kingdom and New York City in the United States, via Cherbourg in France.

An ocean liner is a type of passenger ship primarily used for transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes. Only one ocean liner remains in service today.

Selandia was the name of three ships of the Danish East Asiatic Company, the best known of which, the first MS Selandia of 1912, was the most advanced ocean-going diesel motor ship of her time.

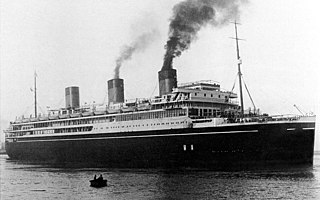

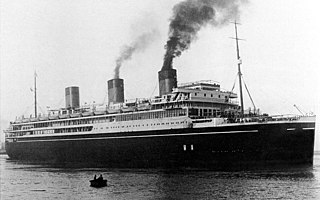

SS Normandie was a French ocean liner built in Saint-Nazaire, France, for the French Line Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT). She entered service in 1935 as the largest and fastest passenger ship afloat, crossing the Atlantic in a record 4.14 days, and remains the most powerful steam turbo-electric-propelled passenger ship ever built.

SS Imperator was a German ocean liner built for the Hamburg America Line, launched in 1912. At the time of her completion in June 1913, she was the largest passenger ship in the world, surpassing the new White Star liner Olympic.

The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, typically known overseas as the French Line, was a French shipping company. Established in 1855 by the brothers Émile and Issac Péreire under the name Compagnie Générale Maritime, the company was entrusted by the French government to transport mails to North America. In 1861, the name of the company was changed to Compagnie Générale Transatlantique. The company's first vessel, SS Washington, had its maiden voyage on 15 June 1864. After a period of trials and errors in the late 19th century, the company, under the direction of its presidents Jules Charles-Roux and John Dal Piaz, gained fame in the 1910s and 1930s with its prestigious ocean liners such as SS Paris, SS Île de France, and especially SS Normandie. Fragilized by the Second World War, the company regained its fame in 1962 with the famous SS France, which suffered major competition from air transport and was retired from service in 1974. In 1977, the company merged with the Compagnie des Messageries Maritimes to form the Compagnie Générale Maritime. Then, in 1996, the company Compagnie Générale Maritime merged to form the CMA CGM.

SS L'Atlantique was a French ocean liner owned by the Compagnie de Navigation Sud Atlantique, a subsidiary of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT). When completed in 1931 she was the largest, swiftest and most luxurious ocean liner on the route between Europe and South America.

Messageries Maritimes was a French merchant shipping company. It was originally created in 1851 as Messageries nationales, later called Messageries impériales, and from 1871, Compagnie des messageries maritimes, casually known as "MesMar" or by its initials "MM". Its rectangular house flag, with the letters MM on a white background and red corners, was famous in shipping circles, especially on the Europe-Asia trade lanes. In 1977 it merged with Compagnie générale transatlantique to form Compagnie générale maritime. In 1996 CGM was privatized and sold to Compagnie Maritime d'Affrètement (CMA) to form CMA CGM.

SS Champlain was a cabin class ocean liner built in 1932 for the French Line by Chantiers et Ateliers de Saint-Nazaire, Penhoët. She was sunk by a mine off La Pallice, France, in 1940—one of the earliest passenger ship losses of the Second World War.

MS Aramis was a Messageries Maritimes ocean liner that was launched in France in 1931. She was a sister ship of Félix Roussel and Georges Philippar. The three sisters were highly unusual in having square funnels. Aramis' interior was an Art Deco interpretation of Minoan design.

MV Astoria is a ship that was constructed as the transatlantic ocean liner Stockholm for Swedish American Line, and rebuilt as a cruise ship in 1993. Ordered in 1944, and commenced service in 1948, at 76 years old, she is the oldest deep water passenger liner still around in a non retired status. As Stockholm, she was best known for an accidental collision with Andrea Doria in July 1956, resulting in the sinking of the latter ship and 46 fatalities off the coast of Nantucket, Massachusetts, United States.

SSCzar was an ocean liner for the then Russian American Line before World War I. In 1920-1930, the ship was named Estonia for the Baltic American Line, then named Pułaski for the PTTO and as a UK Ministry of War Transport troopship, and as Empire Penryn after World War II. The liner was built in Glasgow for the Russian American Line in 1912 and sailed on North Atlantic routes from Liepāja (Libau) to New York. On one eastbound voyage in October 1913, Czar was one of ten ships that came to the aid of the burning Uranium Line steamer Volturno.

SS Stella Solaris was an ocean liner built for Messageries Maritimes in 1953. She mainly provided passenger service between France, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Japan.

Georges Philippar was a French shipbuilder. He joined the Messageries Maritimes company in 1912, becoming its chief executive officer in 1925.

Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft was a Dutch ocean liner built in 1925. An onboard fire destroyed her passenger accommodation before she was completed. In 1932, another fire damaged her so severely that she was sold for scrapping, only to catch fire again before she was scrapped.

Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire (ACL) was a French shipbuilding company of the late 19th and early 20th century. The name translates roughly to English as "Workshops and Shipyard of the Loire".

SS Patria was an 11,885 GRT French ocean liner built in 1913 for Compagnie française de Navigation à vapeur Cyprien Fabre & Cie, for whom she was first a transatlantic liner and then an emigrant ship. From 1932 Fabre Line leased her to Services Contractuels des Messageries Maritimes, who ran her between the south of France and the Levant. After the fall of France in June 1940 the British authorities in Mandatory Palestine seized her in the Port of Haifa and placed her under the management of the British-India Steam Navigation Company. In November 1940, the Zionist movement Haganah planted a bomb aboard which sank her with the loss of between 260 and 300 lives. Patria remained a wreck in Haifa port until she was scrapped in 1952.

RMS Otranto was an ocean liner that was built for the Orient Steam Navigation Company in 1925. The "RMS" prefix stands for Royal Mail Ship, as she carried overseas mail under a contract between Orient Line and Royal Mail. Otranto was in service until 1957, when she was sold for scrap.

SS Viet-Nam was an Ocean Liner built in Dunkirk, France for Messageries Maritimes in 1953. Viet-Nam was built along with two sister ships, the SS Cambodge and SS Laos. She mainly provided passenger service between France, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Japan.

SS Kaisar-i-Hind was a P&O ocean liner that was launched in Scotland in 1914 and scrapped in England in 1938. Kaisar-i-Hind means "Empress of India". She was the second P&O ship to bear this name. The first was launched in 1878 and scrapped in 1898.