The Northern Mariana Islands, officially the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, is an unincorporated territory and commonwealth of the United States consisting of 14 islands in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. The CNMI includes the 14 northernmost islands in the Mariana Archipelago; the southernmost island, Guam, is a separate U.S. territory. The Northern Mariana Islands were listed by the United Nations as a non-self governing territory until 1990.

The pintail or northern pintail is a duck species with wide geographic distribution that breeds in the northern areas of Europe and across the Palearctic and North America. It is migratory and winters south of its breeding range to the equator. Unusually for a bird with such a large range, it has no geographical subspecies if the possibly conspecific duck Eaton's pintail is considered to be a separate species.

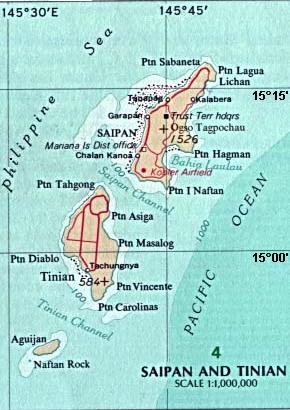

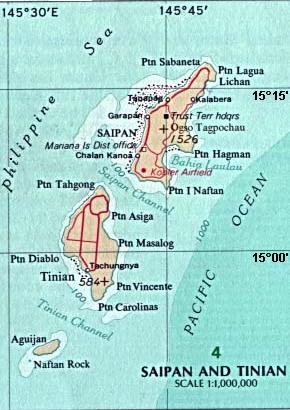

Tinian is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the four constituent municipalities of the Northern Marianas. Tinian's largest village is San Jose. Tinian is just south of the most inhabited island Saipan, but north of the populated Rota to the south. The island is home to many WW2 historical sites, cattle ranches, and beaches. There was a 5-star casino that operated from 1998 to 2016; remaining are other hotels/resorts and a golf course. The main access to Saipan is by a short airplane ride from the international airport, or by a charter boat.

The mallard or wild duck is a dabbling duck that breeds throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Eurasia, and North Africa. It has been introduced to New Zealand, Australia, Peru, Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, the Falkland Islands, and South Africa. This duck belongs to the subfamily Anatinae of the waterfowl family Anatidae. Males have green heads, while the females have mainly brown-speckled plumage. Both sexes have an area of white-bordered black or iridescent purple or blue feathers called a speculum on their wings; males especially tend to have blue speculum feathers. The mallard is 50–65 cm (20–26 in) long, of which the body makes up around two-thirds the length. The wingspan is 81–98 cm (32–39 in) and the bill is 4.4 to 6.1 cm long. It is often slightly heavier than most other dabbling ducks, weighing 0.7–1.6 kg (1.5–3.5 lb). Mallards live in wetlands, eat water plants and small animals, and are social animals preferring to congregate in groups or flocks of varying sizes.

The American black duck is a large dabbling duck in the family Anatidae. It was described by William Brewster in 1902. It is the heaviest species in the genus Anas, weighing 720–1,640 g (1.59–3.62 lb) on average and measuring 54–59 cm (21–23 in) in length with an 88–95 cm (35–37 in) wingspan. It somewhat resembles the female and eclipse male mallard in coloration, but has a darker plumage. The male and female are generally similar in appearance, but the male's bill is yellow while the female's is dull green with dark marks on the upper mandible. It is native to eastern North America. During the breeding season, it is usually found in coastal and freshwater wetlands from Saskatchewan to the Atlantic in Canada and the Great Lakes and the Adirondacks in the United States. It is a partially migratory species, mostly wintering in the east-central United States, especially in coastal areas.

The Indian spot-billed duck is a species of large dabbling duck that is a non-migratory breeding duck throughout freshwater wetlands in the Indian subcontinent. The name is derived from the red spot at the base of the bill that is found in the mainland Indian population. When in water it can be recognized from a long distance by the white tertials that form a stripe on the side, and in flight it is distinguished by the green speculum with a broad white band at the base. This species and the eastern spot-billed duck were formerly considered conspecific, together called the spot-billed duck.

The Laysan duck, also known as the Laysan teal, is a dabbling duck endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. Fossil evidence reveals that Laysan ducks once lived across the entire archipelago, but today survive only on Laysan Island and two atolls. The duck has several physical and behavioral traits linked to the absence of ground-based predators in its habitat. By 1860, the ducks had disappeared from everywhere except Laysan Island. The introduction of European rabbits by guano miners at the end of the 19th century brought the bird to the brink of extinction in 1912, with twelve surviving individuals. Rabbits were eradicated from the island in 1923 and numbers of Laysan ducks began to rise, reaching 500 by the 1950s. In an effort to ensure the long-term future of this duck, 42 birds were translocated to Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge in 2002. These thrived in their new surroundings, and another group were later relocated to Kure Atoll.

The mottled duck or mottled mallard is a medium-sized species of dabbling duck. It is intermediate in appearance between the female mallard and the American black duck. It is closely related to those species, and is sometimes erroneously considered a subspecies of the former.

The crested shelduck, or Korean crested shelduck, is a species of bird in the family Anatidae. It is critically endangered and may be extinct. The male crested shelduck has a greenish-black crown, breast, primaries, and tail, while the rest of its face, chin, and throat are brownish black. The male's belly, undertail coverts, and flanks are a dark grey with black striations. The upper wing coverts are white, while its speculum is an iridescent green. The female has a white eye ring, black crest, white face, chin, throat, neck, and uppers wing coverts and a dark brown body with white striations. Additionally, both sexes have a distinctive green tuft of feathers protruding from the head.

The Pacific black duck is a dabbling duck found in much of Indonesia, New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, and many islands in the southwestern Pacific, reaching to the Caroline Islands in the north and French Polynesia in the east. It is usually called the grey duck in New Zealand, where it is also known by its Maori name, pārera.

Meller's duck is a species of the dabbling duck genus Anas. It is endemic to eastern Madagascar. Although a population was established on Mauritius in the mid-18th century, this is on the verge of extinction due to habitat loss and competition by feral domestic ducks. The species name of this species is after the botanist Charles James Meller, and its generic name is from the Latin for "duck".

The Hawaiian duck or koloa is a species of bird in the family Anatidae that is endemic to the large islands of Hawaiʻi. Taxonomically, the koloa is closely allied with the mallard. It differs in that it is monochromatic and non-migratory. As with many duck species in the genus Anas, Hawaiian duck and mallards can interbreed and produce viable offspring, and the koloa has previously been considered an island subspecies of the mallard. However, all major authorities now consider this form to be a distinct species within the mallard complex. Recent analyses indicate that this is a distinct species that arose through ancient hybridization between mallard and the Laysan duck. The native Hawaiian name for this duck is koloa maoli, or simply koloa. This species is listed as endangered by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and its population trend is decreasing.

Rota, also known as the "Friendly Island", is the southernmost island of the United States Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the third southernmost of the Marianas Archipelago. In early Spanish records it is called "Zarpana"; the name Rota may have come from the Spaniards possibly naming the island after the municipality of Rota, Spain. It lies approximately 40 nautical miles (74 km) north-northeast of the United States territory of Guam. Sinapalo village is the largest and most populated, followed by Songsong village (Songsong). Rota also functions as one of the four municipalities of the CNMI.

The Micronesian megapode or Micronesian scrubfowl is an endangered megapode which inhabits islands of the Western Pacific Ocean.

The Mariana crow is a species of the crow family from the tropical Western Pacific. It is a glossy black bird about 15 inches (38 cm) long and known only from the islands of Guam and Rota.

The Mariana swiftlet or Guam swiftlet is a species of swiftlet in the family Apodidae.

The golden white-eye is a species of bird in the white-eye family, Zosteropidae. It is the only species within the genus Cleptornis. The golden white-eye was once considered to be a honeyeater in the family Meliphagidae and although it is now known to be a white-eye, its position within that family is still uncertain. The species is restricted to the islands of Saipan and Aguijan in the Northern Mariana Islands, where it is sympatric and competes with the related bridled white-eye. The golden white-eye has golden plumage and a pale eye-ring. It feeds on insects, fruit, and nectar and forages in pairs or small family groups. The bird is monogamous and lays two eggs in a small cup nest.

The bridled white-eye is a species of white-eye native to the Mariana Islands and formerly Guam. The species' natural habitat is tropical forests, shrublands and urban areas.

Star Marianas Air, Inc. is a U.S. commuter airline headquartered at Tinian International Airport in Tinian Municipality, Northern Mariana Islands. It operates scheduled and charter passenger service in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam, both U.S. territories in the Pacific Ocean.

The Marianas tropical dry forests is a tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests ecoregion on the Marianas Islands in the western Pacific Ocean.