The Etruscan civilization was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in ancient Italy, with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roughly what is now Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio, as well as what are now the Po Valley, Emilia-Romagna, south-eastern Lombardy, southern Veneto, and western Campania.

Umbria is a region of central Italy. It includes Lake Trasimeno and Marmore Falls, and is crossed by the Tiber. It is the only landlocked region on the Apennine Peninsula. The regional capital is Perugia.

Etruria was a region of Central Italy delimited by the rivers Arno and Tiber, an area that covered what is now most of Tuscany, northern Lazio, and north-western Umbria.

Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and religion. As the Etruscan civilization was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC, the Etruscan religion and mythology were partially incorporated into ancient Roman culture, following the Roman tendency to absorb some of the local gods and customs of conquered lands. The first attestations of an Etruscan religion can be traced back to the Villanovan culture.

Aita, also spelled Eita, is an epithet of the Etruscan chthonic fire god Śuri as god of the underworld, roughly equivalent to the Greek god Hades.

In Etruscan mythology, Tarchon and his brother, Tyrrhenus, were culture heroes who founded the Etruscan League of twelve cities, the Dodecapoli. One author, Joannes Laurentius Lydus, distinguishes two legendary persons named Tarchon, the Younger and his father, the Elder. It was the Elder who received the Etrusca Disciplina from Tages, whom he identifies as a parable. The Younger fought with Aeneas after his arrival in Italy. The elder was a haruspex, who learned his art from Tyrrhenus, and was probably the founder of Tarquinia and the Etruscan League. Lydus does not state that, but the connection was being made at least as long ago as George Dennis. Lydus had the advantage in credibility, even though late, of stating that he read the part of the Etrusca Disciplina about Tages and that it was a dialogue with Tarchon's lines in "the ordinary language of the Italians" and Tages' lines in Etruscan, which was difficult for him to read. He relied on translations.

Todi is a town and comune (municipality) of the province of Perugia in central Italy. It is perched on a tall two-crested hill overlooking the east bank of the river Tiber, commanding distant views in every direction. It was founded in antiquity by the Umbri, at the border with Etruria; the family of Roman Emperor Trajan came from Todi.

Volsinii or Vulsinii, is the name of two ancient cities of Etruria, one situated on the shore of Lacus Volsiniensis, and the other on the Via Clodia, between Clusium (Chiusi) and Forum Cassii (Vetralla). The latter was Etruscan and was destroyed by the Romans in 264 BC following an attempted revolt by its slaves, while the former was founded by the Romans using the remainder of the Etruscan population rescued from the razed city.

The Etruscan alphabet was the alphabet used by the Etruscans, an ancient civilization of central and northern Italy, to write their language, from about 700 BC to sometime around 100 AD.

Regio VI Umbria is the name for one of the 11 administrative regions into which the emperor Augustus divided Italy. The main source for the regions is the Historia Naturalis of Pliny the Elder, who informs his readers he is basing the geography of Italy on the descriptio Italiae, "division of Italy", made by Augustus. The Regio Sexta is called Umbria complexa agrumque Gallicam citra Ariminium.

The Umbri were an Italic people of ancient Italy. A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the ancient Umbria.

Etruscan cities were a group of ancient settlements that shared a common Etruscan language and culture, even though they were independent city-states. They flourished over a large part of the northern half of Italy starting from the Iron Age, and in some cases reached a substantial level of wealth and power. They were eventually assimilated first by Italics in the south, then by Celts in the north and finally in Etruria itself by the growing Roman Republic.

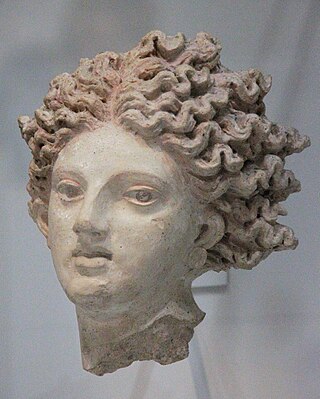

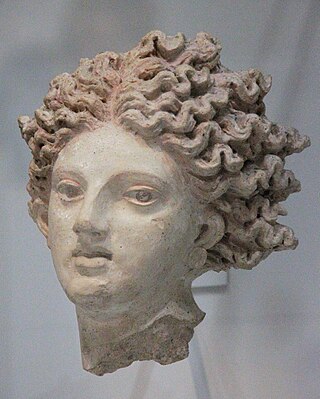

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

Larissa Bonfante was an Italian-American classicist, Professor of Classics emerita at New York University and an authority on Etruscan language and culture.

Usil is the Etruscan god of the sun, shown to be identified with Apulu (Apollo). His iconic depiction features Usil rising out of the sea, with a fireball in either outstretched hand, on an engraved Etruscan bronze mirror in late Archaic style, formerly on the Roman antiquities market. On Etruscan mirrors in the Classical style, Usil appears with an aureole.

Vegoia is a sibyl, prophet, or nymph within the Etruscan religious framework who is identified as the author of parts of their large and complex set of sacred books, detailing the religiously correct methods of founding cities and shrines, draining fields, formulating laws and ordinances, measuring space and dividing time; she initiated the Etruscan people to the arts, as originating the rules and rituals of land marking, and as presiding over the observance, respect, and preservation of boundaries. Vegoia also is known as Vecu, Vecui, and Vecuvia, as well as Vegoe; her name is also given as Begoe or Bigois.

Satre or Satres was an Etruscan god who appears on the Liver of Piacenza, a bronze model used for haruspicy. He occupies the dark and negative northwest region, and seems to be a "frightening and dangerous god who hurls his lightning from his abode deep in the earth." It is possible that Satre is also referred to with the word "satrs" in the Liber Linteus, the Etruscan text preserved in Ptolemaic Egypt as mummy wrappings.

Catha is a female Etruscan lunar or solar deity, who may also be connected to childbirth, and has a connection to the underworld. Catha is also the goddess of the south sanctuary at Pyrgi, Italy.

Apulu, also syncopated as Aplu, is an epithet of the Etruscan fire god Śuri as chthonic sky god, roughly equivalent to the Greco-Roman god Apollo. Their names are associated on Pyrgi inscriptions too. The name Apulu or Aplu did not come directly from Greece but via a Latin center, probably Palestrina.