Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are primarily found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of the defining features of marsupials is their unique reproductive strategy, where the young are born in a relatively undeveloped state and then nurtured within a pouch.

Ungulates are members of the diverse clade Euungulata, which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to be a polyphyletic and thereby invalid clade based on molecular data. As a result, true ungulates had since been reclassified to the newer clade Euungulata in 2001 within the clade Laurasiatheria while Paenungulata has been reclassified to a distant clade Afrotheria. Living ungulates are divided into two orders: Perissodactyla including equines, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and Artiodactyla including cattle, antelope, pigs, giraffes, camels, sheep, deer, and hippopotamuses, among others. Cetaceans such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises are also classified as artiodactyls, although they do not have hooves. Most terrestrial ungulates use the hoofed tips of their toes to support their body weight while standing or moving. Two other orders of ungulates, Notoungulata and Litopterna, both native to South America, became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago.

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name molar derives from Latin, molaris dens, meaning "millstone tooth", from mola, millstone and dens, tooth. Molars show a great deal of diversity in size and shape across the mammal groups. The third molar of humans is sometimes vestigial.

The order Peramelemorphia includes the bandicoots and bilbies. All members of the order are endemic to Australia-New Guinea and most have the characteristic bandicoot shape: a plump, arch-backed body with a long, delicately tapering snout, very large upright ears, relatively long, thin legs, and a thin tail. Their size varies from about 140 grams up to 4 kilograms, but most species are about one kilogram.

Notoryctidae are a family of marsupials comprising the marsupial moles and their fossil relatives. It is the only family in the order Notoryctemorphia.

The family Talpidae includes the moles who are small insectivorous mammals of the order Eulipotyphla. Talpids are all digging animals to various degrees: moles are completely subterranean animals; shrew moles and shrew-like moles somewhat less so; and desmans, while basically aquatic, excavate dry sleeping chambers; whilst the quite unique star-nosed mole is equally adept in the water and underground. Talpids are found across the Northern Hemisphere of Eurasia and North America, and range as far south as the montane regions of tropical Southeast Asia.

Australidelphia is the superorder that contains roughly three-quarters of all marsupials, including all those native to Australasia and a single species — the monito del monte — from South America. All other American marsupials are members of the Ameridelphia. Analysis of retrotransposon insertion sites in the nuclear DNA of a variety of marsupials has shown that the South American monito del monte's lineage is the most basal of the superorder.

The Arvicolinae are a subfamily of rodents that includes the voles, lemmings, and muskrats. They are most closely related to the other subfamilies in the Cricetidae. Some authorities place the subfamily Arvicolinae in the family Muridae along with all other members of the superfamily Muroidea. Some refer to the subfamily as the Microtinae or rank the taxon as a full family, the Arvicolidae.

Yalkaparidon is an extinct genus of Australian marsupials, first described in 1988 and known only from the Oligo-Miocene deposits of Riversleigh, northwestern Queensland, Australia.

Sparassodonta is an extinct order of carnivorous metatherian mammals native to South America, related to modern marsupials. They were once considered to be true marsupials, but are now thought to be a separate side branch that split before the last common ancestor of all modern marsupials. A number of these mammalian predators closely resemble placental predators that evolved separately on other continents, and are cited frequently as examples of convergent evolution. They were first described by Florentino Ameghino, from fossils found in the Santa Cruz beds of Patagonia. Sparassodonts were present throughout South America's long period of "splendid isolation" during the Cenozoic; during this time, they shared the niches for large warm-blooded predators with the flightless terror birds. Previously, it was thought that these mammals died out in the face of competition from "more competitive" placental carnivorans during the Pliocene Great American Interchange, but more recent research has showed that sparassodonts died out long before eutherian carnivores arrived in South America. Sparassodonts have been referred to as borhyaenoids by some authors, but currently the term Borhyaenoidea refers to a restricted subgroup of sparassodonts comprising borhyaenids and their close relatives.

The Australosphenida are a clade of mammals, containing mammals with tribosphenic molars, known from the Jurassic to Mid-Cretaceous of Gondwana. Although they have often been suggested to have acquired tribosphenic molars independently from those of Tribosphenida, this has been disputed. Fossils of australosphenidans have been found from the Jurassic of Madagascar and Argentina, and Cretaceous of Australia and Argentina. Monotremes have also been considered a part of this group in many studies, but this is also disputed.

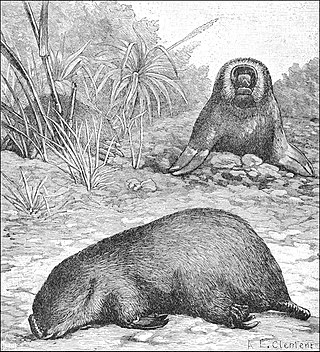

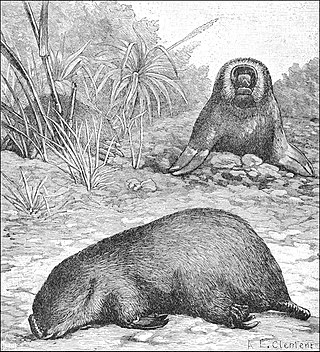

The southern marsupial mole, also known as the itjaritjari or itjari-itjari, is a mole-like marsupial found in the western central deserts of Australia. It is extremely adapted to a burrowing way of life. It has large, shovel-like forepaws and silky fur, which helps it move easily. It also lacks complete eyes as it has little need for them. It feeds on earthworms and larvae.

The northern marsupial mole or kakarratul is a marsupial in the family Notoryctidae, an endemic animal of arid regions of Central Australia. It lives in the loose sand of dunes and river plains in the desert, spending nearly its entire life beneath ground. The facial features are reduced or absent, their small and strong body, weighing little more the 30 grams, is extremely specialised to moving through sand in search of prey. The species is elusive and it is one of the most poorly understood mammals of Australia.

Hulitherium tomasetti is an extinct zygomaturine marsupial that lived in New Guinea during the Pleistocene. The species name honours Berard Tomasetti, a Catholic priest in Papua New Guinea, who brought the fossils to the attention of experts.

Kuehneotherium is an early mammaliaform genus, previously considered a holothere, that lived during the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic Epochs and is characterized by reversed-triangle pattern of molar cusps. Although many fossils have been found, the fossils are limited to teeth, dental fragments, and mandible fragments. The genus includes Kuehneotherium praecursoris and all related species. It was first named and described by Doris M. Kermack, K. A. Kermack, and Frances Mussett in November 1967. The family Kuehneotheriidae and the genus Kuehneotherium were created to house the single species Kuehneotherium praecursoris. Modeling based upon a comparison of the Kuehneotherium jaw with other mammaliaforms indicates it was about the size of a modern-day shrew between 4 and 5.5 g at adulthood.

Naraboryctes philcreaseri is a fossil species of marsupial found at early Miocene deposits of Boodjamulla National Park of Riversleigh area, northwestern Queensland, Australia.

The Macropodidae are an extant family of marsupial with the distinction of the ability to move bipedally on the hind legs, sometimes by jumping, as well as quadrupedally. They are herbivores, but some fossil genera like Ekaltadeta are hypothesised to have been carnivores. The taxonomic affiliations within the family and with other groups of marsupials is still in flux. Macropodids are considered to be the most diverse group of marsupial herbivores ever to have evolved, and have been the subject of more phylogenetic studies than any other marsupial family.

Necrolestes is an extinct genus of mammals, which lived during the Early Miocene in what is now Argentine Patagonia. It is the most recent known genus of Meridiolestida, an extinct group of mammals more closely related to therians than to monotremes, which were the dominant mammals in South America during the Late Cretaceous. It contains two species, N. patagonensis and N. mirabilis; the type species N. patagonensis was named by Florentino Ameghino in 1891 based on remains found by his brother, Carlos Ameghino in Patagonia. Fossils of Necrolestes have been found in the Sarmiento and Santa Cruz Formations. Its morphology suggests that it was a digging, subterranean-dwelling mole-like mammal that fed on invertebrates.

Siamoperadectes is a genus of non-marsupial metatherian from the Miocene of Thailand. A member of Peradectidae, it is the first member of its clade known from South Asia, and among the last non-marsupial metatherians.

Xenocranium is an extinct monotypic genus of placental mammal from extinct paraphyletic subfamily Epoicotheriinae within extinct paraphyletic family Epoicotheriidae in extinct order Palaeanodonta, that lived in North America during the late Eocene.