A firearm is any type of gun that uses an explosive charge and is designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries.

The percussion cap or percussion primer, introduced in the early 1820s, is a type of single-use percussion ignition device for muzzle loader firearm locks enabling them to fire reliably in any weather condition. Its invention gave rise to the cap lock mechanism or percussion lock system which used percussion caps struck by the hammer to set off the gunpowder charge in rifles and cap and ball firearms. Any firearm using a caplock mechanism is a percussion gun. Any long gun with a cap-lock mechanism and rifled barrel is a percussion rifle. Cap and ball describes cap-lock firearms discharging a single bore-diameter spherical bullet with each shot.

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism itself, also known as the true flintlock, that was introduced in the early 17th century, and gradually replaced earlier firearm-ignition technologies, such as the matchlock, the wheellock, and the earlier flintlock mechanisms such as the snaplock and snaphaunce.

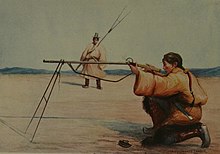

An arquebus is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually disappeared as the use of heavy armour declined, but musket continued as the generic term for smoothbore long guns until the mid-19th century. In turn, this style of musket was retired in the 19th century when rifled muskets using the Minié ball became common. The development of breech-loading firearms using self-contained cartridges and the first reliable repeating rifles produced by Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1860 also led to their demise. By the time that repeating rifles became common, they were known as simply "rifles", ending the era of the musket.

A wheellock, wheel-lock, or wheel lock is a friction-wheel mechanism which creates a spark that causes a firearm to fire. It was the next major development in firearms technology after the matchlock and the first self-igniting firearm. Its name is from its rotating steel wheel to provide ignition. Developed in Europe around 1500, it was used alongside the matchlock and later the snaplock (1540s), the snaphance (1560s), and the flintlock.

A snaphance or snaphaunce is a type of firearm lock in which a flint struck against a striker plate above a steel pan ignites the priming powder which fires the gun. It is the mechanical progression of the wheellock firing mechanism, and along with the miquelet lock and doglock are predecessors of the flintlock mechanism.

Early modern warfare is the era of warfare following medieval warfare. It is associated with the start of the widespread use of gunpowder and the development of suitable weapons to use the explosive, including artillery and firearms; for this reason the era is also referred to as the age of gunpowder warfare. This entire period is contained within the Age of Sail, which characteristic dominated the era's naval tactics, including the use of gunpowder in naval artillery.

The lock of a firearm is the mechanism used to initiate firing. It is a historical term, in that it generally refers to such mechanisms used in muzzle-loading and early breech-loading firearms. Side-lock refers to the type of construction, in which the individual components of the mechanism are mounted either side of a single plate. The assembly is then mounted to the stock on the side of the firearm. In modern firearm designs, the mechanism to initiate firing is generally constructed within the frame or receiver of the firearm and is referred to as the firing or trigger mechanism.

A snaplock is a type of lock for firing a gun or is a gun fired by such a lock.

The snap matchlock is a type of matchlock mechanism used to ignite early firearms. It was used in Europe from about 1475 to 1640, and in Japan from 1543 until about 1880, and was also largely used by Korea (Joseon) during the Imjin war to the early 20th century.

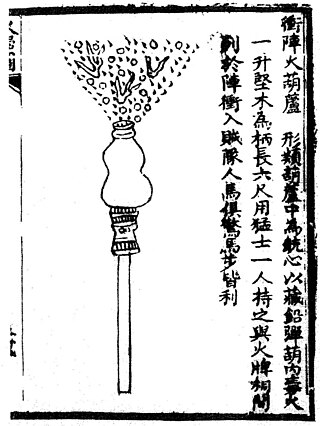

The history of firearms begins in 10th-century China, when tubes containing gunpowder and pellet projectiles were mounted on spears to make portable fire lances, operable by one person. This was later used effectively as a shock weapon in the Siege of De'an in 1132. In the 13th century, fire lance barrels were replaced with metal tubes and transformed into metal-barreled hand cannons. The technology gradually spread throughout Eurasia during the 14th century and evolved into flintlocks, blunderbusses, and other variants. The 19th and 20th centuries saw an acceleration in this evolution, with the introduction of the magazine, belt-fed weapons, metal cartridges, and the automatic firearm. Older firearms typically used black powder as a propellant, but modern firearms use smokeless powder or other propellants. Most modern firearms have rifled barrels.

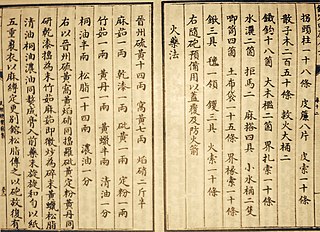

Gunpowder is the first explosive to have been developed. Popularly listed as one of the "Four Great Inventions" of China, it was invented during the late Tang dynasty while the earliest recorded chemical formula for gunpowder dates to the Song dynasty. Knowledge of gunpowder spread rapidly throughout Asia and Europe, possibly as a result of the Mongol conquests during the 13th century, with written formulas for it appearing in the Middle East between 1240 and 1280 in a treatise by Hasan al-Rammah, and in Europe by 1267 in the Opus Majus by Roger Bacon. It was employed in warfare to some effect from at least the 10th century in weapons such as fire arrows, bombs, and the fire lance before the appearance of the gun in the 13th century. While the fire lance was eventually supplanted by the gun, other gunpowder weapons such as rockets and fire arrows continued to see use in China, Korea, India, and this eventually led to its use in the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. Bombs too never ceased to develop and continued to progress into the modern day as grenades, mines, and other explosive implements. Gunpowder has also been used for non-military purposes such as fireworks for entertainment, or in explosives for mining and tunneling.

A gun is a device designed to propel a projectile using pressure or explosive force. The projectiles are typically solid, but can also be pressurized liquid, or gas. Solid projectiles may be free-flying or tethered. A large-caliber gun is also called a cannon.

Firearms were introduced to Japan in the 13th century during the first Mongol invasion, referred to as teppō. Portuguese firearms were introduced in 1543, and intense development followed, with strong local manufacture during the period of conflicts of the late 16th century. Hōjutsu, the art of gunnery, is the Japanese martial art dedicated to firearms usage.

The gunpowder empires, or Islamic gunpowder empires, is a collective term coined by Marshall G. S. Hodgson and William H. McNeill at the University of Chicago, referring to three early modern Muslim empires: the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire and the Mughal Empire, in the period they flourished from mid-16th to the early 18th century. These three empires were among the most stable empires of the early modern period, leading to commercial expansion, and patronage of culture, while their political and legal institutions were consolidated with an increasing degree of centralization. They stretched from Central Europe and North Africa in the west to Bengal and Arakan in the east. Hodgson's colleague William H. McNeill expanded on the history of gunpowder use across multiple civilizations including East Asian, South Asian and European powers in his "The Age of Gunpowder Empires". Vast amounts of territory were conquered by the gunpowder empires with the use and development of the newly invented firearms, especially cannon and small arms, in the course of imperial expansion. Like in Europe, the introduction of gunpowder weapons prompted changes such as the rise of centralized monarchical states.

Tanegashima, most often called in Japanese and sometimes in English hinawajū, was a type of matchlock-configured arquebus firearm introduced to Japan through the Portuguese Empire in 1543. It was used by the samurai class and their ashigaru "foot soldiers", and within a few years its introduction in battle changed the way war was fought in Japan forever. It, however, could not completely replace the yumi (longbow). Although the Japanese developed various techniques to improve the gun's shortcomings, specifically its slow rate of fire and inability to fire in the rain, it remained inferior to the yumi in these respects, and the latter continued to be an important weapon on the battlefield. After Tokugawa Ieyasu destroyed the Toyotomi clan in the siege of Osaka and established the Tokugawa shogunate, the relatively peaceful Edo period arrived, and the use of tanegashima declined.

This is a timeline of the history of gunpowder and related topics such as weapons, warfare, and industrial applications. The timeline covers the history of gunpowder from the first hints of its origin as a Taoist alchemical product in China until its replacement by smokeless powder in the late 19th century.

Istinggar is a type of matchlock firearm built by the various ethnic groups of the Maritime Southeast Asia. The firearm is a result of Portuguese influence on local weaponry after the capture of Malacca (1511). Before this type of gun, in the archipelago already existed early long gun called bedil, or Java arquebus as the Chinese call it. Most of the specimens in the Malay Peninsula are actually Indonesian in origin, manufactured in the Minangkabau lands of West Sumatra. The states of the Malay Peninsula imported this firearm as it was widely used in their wars.

Jiaozhi arquebus refers to several types of gunpowder firearms produced historically in Vietnam. This page also includes Vietnamese muskets — since the early definition of a musket is a "heavy arquebus". The term Jiaozhi arquebus comes from Chinese word Jiao Chong, a generalization of firearms originating from Dai Viet.