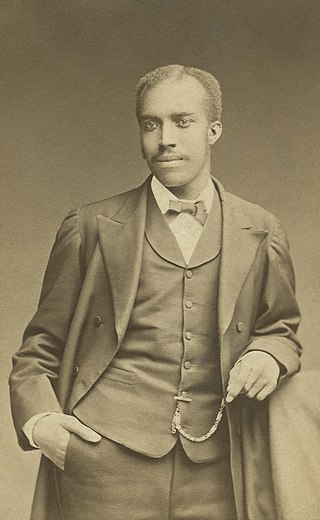

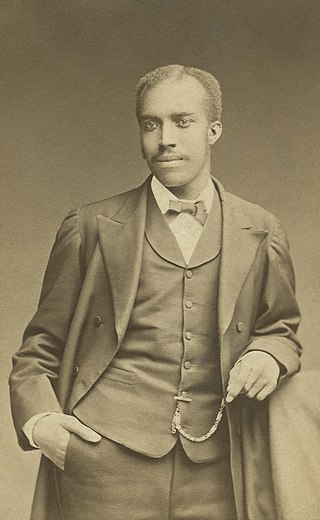

Nathan Francis Mossell was the first African-American graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1882. He did post-graduate training at hospitals in Philadelphia and London. In 1888, he was the first black physician elected as member of the Philadelphia County Medical Society in Pennsylvania. He helped found the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School in West Philadelphia in 1895, which he led as chief-of-staff and medical director until he retired in 1933. Gertrude Bustill Mossell was his wife.

Matilda Evans, M.D., also known as Matilda Arabella Evans was the first African-American woman licensed to practice medicine in South Carolina and an advocate for improved health care for African Americans, particularly children.

Rudolph John Chauncey Fisher was an American physician, radiologist, novelist, short story writer, dramatist, musician, and orator. His father was John Wesley Fisher, a clergyman, his mother was Glendora Williamson Fisher, and he had two siblings. Fisher married Jane Ryder, a school teacher from Washington, D.C. in 1925, and they had one son, Hugh, who was born in 1926 and was also nicknamed "The New Negro" as a tribute to the Harlem renaissance. Fisher had a successful career as an innovative doctor and author, who discussed the dynamics and relationships of Black and White people living in Harlem. This racial conflict was a central theme in many of his works.

Patricia Era Bath was an American ophthalmologist and humanitarian. She became the first female member of the Jules Stein Eye Institute, the first woman to lead a post-graduate training program in ophthalmology, and the first woman elected to the honorary staff of the UCLA Medical Center. Bath was the first African-American to serve as a resident in ophthalmology at New York University. She was also the first African-American woman to serve on staff as a surgeon at the UCLA Medical Center. Bath was the first African-American woman doctor to receive a patent for a medical purpose. A holder of five patents, she founded the non-profit American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness in Washington, D.C.

Harlem Hospital Center, branded as NYC Health + Hospitals/Harlem, is a 272-bed, public teaching hospital affiliated with Columbia University. It is located at 506 Lenox Avenue in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City and was founded on April 18, 1887.

Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS was an American surgeon and civil rights activist. In his position at Harlem Hospital he was the first African-American on the surgical staff of a non-segregated hospital in New York City. He was influential for his medical research as well as his efforts pushing for racial equality in medicine and involvement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he served as chairman for nearly two decades.

Jane Cooke Wright was a pioneering cancer researcher and surgeon noted for her contributions to chemotherapy. In particular, Wright is credited with developing the technique of using human tissue culture rather than laboratory mice to test the effects of potential drugs on cancer cells. She also pioneered the use of the drug methotrexate to treat breast cancer and skin cancer.

Dorothy Lavinia Brown, also known as "Dr. D.", was an African-American surgeon, legislator, and teacher. She was the first female surgeon of African-American ancestry from the Southeastern United States. She was also the first African American female to serve in the Tennessee General Assembly as she was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. While serving in the House of Representatives, Brown fought for women's rights and for the rights of people of color.

Charles Howard Wright was a Detroit physician and founder of the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History.

Yvonne S. Thornton is an American obstetrician-gynecologist, musician and author, best known for her memoir, The Ditchdigger's Daughters.

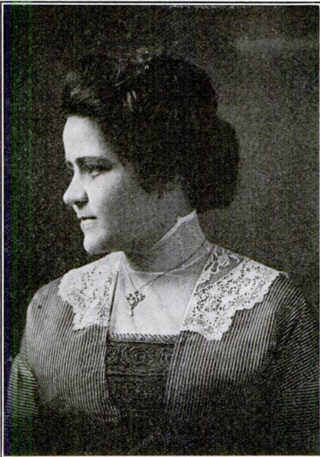

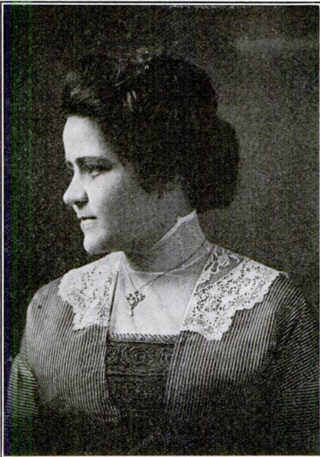

Caroline Still Anderson was an American physician, educator, and activist. She was a pioneering physician in the Philadelphia African-American community and one of the first Black women to become a physician in the United States.

Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier was an American physician who founded the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women. Dr. Lozier was also a noted feminist and activist, and served as president of the New York City Suffrage League and the National Women's Suffrage Association.

Muriel Petioni was a medical doctor and community activist in Harlem. She was known as the "matron of Harlem health" because she sought to fulfill the healthcare needs of the underprivileged people in Harlem.

Myra Adele Logan is known as the first African American female physician, surgeon, and anatomist to perform a successful open-heart surgery. Following this accomplishment, Logan focused her work on children's heart surgery and was involved in the development of the antibiotic Aureomycin which treated bacterial, viral, and rickettsial diseases with the majority of her medical practice done at the Harlem Hospital in New York. Logan attended medical school during the pre–Civil Rights era. The majority of black female physicians in this time period were forced to attend segregated schools. Earning a medical degree as an African American woman during this time period was extremely difficult.

Margaret Cornelia Morgan Lawrence was an American psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, gaining those qualifications in 1948. Her work included clinical care, teaching, and research, particularly into the presence and development of ego strength in inner-city families. Lawrence studied young children identified as "strong" by their teachers in Georgia and Mississippi, as well as on sabbatical in Africa in 1973, writing two books on mental health of children and inner-city families. Lawrence was chief of the Developmental Psychiatry Service for Infants and Children at Harlem Hospital for 21 years, as well as associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S), retiring in 1984.

Grace Marilyn James was an American pediatrician in Louisville, Kentucky. When she began practicing medicine in 1953, the hospitals in Louisville were racially segregated by law. At the University of Louisville School of Medicine she was the first African-American physician on the faculty. She was also one of the first two African-American women on the faculty at any southern medical school. Additionally, she was first African-American woman to serve as an attending physician at Louisville's Kosair Children's Hospital.

Edith Irby Jones was an American physician who was the first African American to be accepted as a non-segregated student at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and the first black student to attend racially mixed classes in the American South. She was the first African American to graduate from a southern medical school, first black intern in the state of Arkansas, and later first black intern at Baylor College of Medicine.

Isabella Vandervall (1894–1989) was an African-American physician, gynecologist and a prominent advocate for the birth control movement in New York City. She attended the New York Medical College for Women, from which she graduated at the top of her class.

Marie Bernadette Lucas was an African American physician, one of the earliest women to practice medicine in Washington, D.C.