Explanations

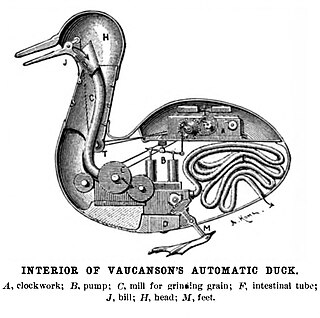

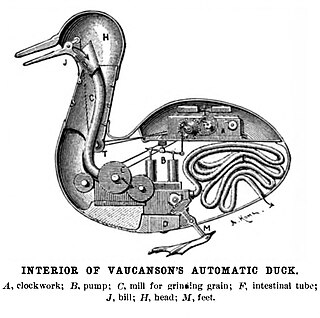

Mechanistic explanations come in many forms. Wesley Salmon proposed what he called the "ontic" conception of explanation, which states that explanations are mechanisms and causal processes in the world. There are two such kinds of explanation: etiological and constitutive. Salmon focused primarily on etiological explanation, with respect to which one explains some phenomenon P by identifying its causes (and, thus, locating it within the causal structure of the world). Constitutive (or componential) explanation, on the other hand, involves describing the components of a mechanism M that is productive of (or causes) P. Indeed, whereas (a) one may differentiate between descriptive and explanatory adequacy, where the former is characterized as the adequacy of a theory to account for at least all the items in the domain (which need explaining), and the latter as the adequacy of a theory to account for no more than those domain items, and (b) past philosophies of science differentiate between descriptions of phenomena and explanations of those phenomena, in the non-ontic context of mechanism literature, descriptions and explanations seem to be identical. This is to say, to explain a mechanism M is to describe it (specify its components, as well as background, enabling, and so on, conditions that constitute, in the case of a linear mechanism, its "start conditions").

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various mental phenomena, like perception, pain experience, belief, desire, intention, and emotion. Various overlapping classifications of mental phenomena have been proposed. Important distinctions group them according to whether they are sensory, propositional, intentional, conscious, or occurrent. Minds were traditionally understood as substances but it is more common in the contemporary perspective to conceive them as properties or capacities possessed by humans and higher animals. Various competing definitions of the exact nature of the mind or mentality have been proposed. Epistemic definitions focus on the privileged epistemic access the subject has to these states. Consciousness-based approaches give primacy to the conscious mind and allow unconscious mental phenomena as part of the mind only to the extent that they stand in the right relation to the conscious mind. According to intentionality-based approaches, the power to refer to objects and to represent the world is the mark of the mental. For behaviorism, whether an entity has a mind only depends on how it behaves in response to external stimuli while functionalism defines mental states in terms of the causal roles they play. Central questions for the study of mind, like whether other entities besides humans have minds or how the relation between body and mind is to be conceived, are strongly influenced by the choice of one's definition.

In philosophy, systems theory, science, and art, emergence occurs when an entity is observed to have properties its parts do not have on their own, properties or behaviors that emerge only when the parts interact in a wider whole.

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and considerations. The opposite of determinism is some kind of indeterminism and even more so nondeterminism. Determinism shares similarities with eternalism with a focus on particular events rather than the future as a concept entirely. Determinism is often contrasted with free will, although some philosophers claim that the two are compatible.

Essentialism is the view that objects have a set of attributes that are necessary to their identity. In early Western thought, Plato's idealism held that all things have such an "essence"—an "idea" or "form". In Categories, Aristotle similarly proposed that all objects have a substance that, as George Lakoff put it, "make the thing what it is, and without which it would be not that kind of thing". The contrary view—non-essentialism—denies the need to posit such an "essence'".

Reductionism is any of several related philosophical ideas regarding the associations between phenomena which can be described in terms of other simpler or more fundamental phenomena. It is also described as an intellectual and philosophical position that interprets a complex system as the sum of its parts.

Teleology or finality is a reason or an explanation for something which serves as a function of its end, its purpose, or its goal, as opposed to something which serves as a function of its cause.

In philosophy of mind, functionalism is the thesis that each and every mental state is constituted solely by its functional role, which means its causal relation to other mental states, sensory inputs, and behavioral outputs. Functionalism developed largely as an alternative to the identity theory of mind and behaviorism.

A scientific theory is an explanation of an aspect of the natural world and universe that has been repeatedly tested and corroborated in accordance with the scientific method, using accepted protocols of observation, measurement, and evaluation of results. Where possible, theories are tested under controlled conditions in an experiment. In circumstances not amenable to experimental testing, theories are evaluated through principles of abductive reasoning. Established scientific theories have withstood rigorous scrutiny and embody scientific knowledge.

An explanation is a set of statements usually constructed to describe a set of facts which clarifies the causes, context, and consequences of those facts. It may establish rules or laws, and may clarify the existing rules or laws in relation to any objects or phenomena examined.

The deductive-nomological model of scientific explanation, also known as Hempel's model, the Hempel–Oppenheim model, the Popper–Hempel model, or the covering law model, is a formal view of scientifically answering questions asking, "Why...?". The DN model poses scientific explanation as a deductive structure, one where truth of its premises entails truth of its conclusion, hinged on accurate prediction or postdiction of the phenomenon to be explained.

Wesley Charles Salmon was an American philosopher of science renowned for his work on the nature of scientific explanation. He also worked on confirmation theory, trying to explicate how probability theory via inductive logic might help confirm and choose hypotheses. Yet most prominently, Salmon was a realist about causality in scientific explanation, although his realist explanation of causality drew ample criticism. Still, his books on scientific explanation itself were landmarks of the 20th century's philosophy of science, and solidified recognition of causality's important roles in scientific explanation, whereas causality itself has evaded satisfactory elucidation by anyone.

In ontology, ontic is physical, real, or factual existence.

The term social mechanisms and mechanism-based explanations of social phenomena originate from the philosophy of science.

Anomalous monism is a philosophical thesis about the mind–body relationship. It was first proposed by Donald Davidson in his 1970 paper "Mental Events". The theory is twofold and states that mental events are identical with physical events, and that the mental is anomalous, i.e. under their mental descriptions, relationships between these mental events are not describable by strict physical laws. Hence, Davidson proposes an identity theory of mind without the reductive bridge laws associated with the type-identity theory. Since the publication of his paper, Davidson refined his thesis and both critics and supporters of anomalous monism have come up with their own characterizations of the thesis, many of which appear to differ from Davidson's.

Human nature is a concept that denotes the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—that humans are said to have naturally. The term is often used to denote the essence of humankind, or what it 'means' to be human. This usage has proven to be controversial in that there is dispute as to whether or not such an essence actually exists.

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addressed, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of particular mental states. Aspects of the mind that are studied include mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and its neural correlates, the ontology of the mind, the nature of cognition and of thought, and the relationship of the mind to the body.

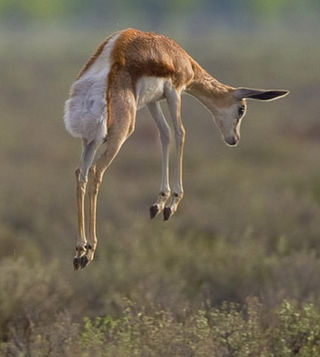

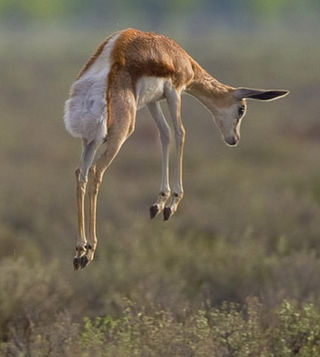

In evolutionary biology, function is the reason some object or process occurred in a system that evolved through natural selection. That reason is typically that it achieves some result, such as that chlorophyll helps to capture the energy of sunlight in photosynthesis. Hence, the organism that contains it is more likely to survive and reproduce, in other words the function increases the organism's fitness. A characteristic that assists in evolution is called an adaptation; other characteristics may be non-functional spandrels, though these in turn may later be co-opted by evolution to serve new functions.

John A. Dupré is a British philosopher of science. He is the director of Egenis, the Centre for the Study of Life Sciences, and professor of philosophy at the University of Exeter. Dupré's chief work area lies in philosophy of biology, philosophy of the social sciences, and general philosophy of science. Dupré, together with Nancy Cartwright, Ian Hacking, Patrick Suppes and Peter Galison, are often grouped together as the "Stanford School" of philosophy of science.

Peter K. Machamer is an American philosopher and historian of science. Machamer was Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh. His work has been influential in philosophy of science in developing an account of mechanistic explanation which rejects standard deductive models of explanation, such as the deductive-nomological model by understanding scientific practice as the search for mechanisms. His research has also focused on 17th-century history of philosophy and science, on Galileo Galilei and René Descartes in particular, and on values and science. He was also a wine columnist for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette for fifteen years, and he has reflected on wine and beer in philosophical writing. Machamer is also the "Philosopher in Residence" for the Pittsburgh dance company Attack Theater.

Teleology in biology is the use of the language of goal-directedness in accounts of evolutionary adaptation, which some biologists and philosophers of science find problematic. The term teleonomy has also been proposed. Before Darwin, organisms were seen as existing because God had designed and created them; their features such as eyes were taken by natural theology to have been made to enable them to carry out their functions, such as seeing. Evolutionary biologists often use similar teleological formulations that invoke purpose, but these imply natural selection rather than actual goals, whether conscious or not. Biologists and religious thinkers held that evolution itself was somehow goal-directed (orthogenesis), and in vitalist versions, driven by a purposeful life force. With evolution working by natural selection acting on inherited variation, the use of teleology in biology has attracted criticism, and attempts have been made to teach students to avoid teleological language.