Play (help·info).

Play (help·info).Melody type or type-melody [2] is a set of melodic formulas, figures, and patterns.

Play (help·info).

Play (help·info).Melody type or type-melody [2] is a set of melodic formulas, figures, and patterns.

"Melody type" is a fundamental notion for understanding a nature of Western and non-Western musical modes, according to Harold Powers' seminal article "Mode" in the first edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians ( Powers 1980 , 12:376–77, 379, et passim).

Melody types are used in the composition of an enormous variety of music, especially non-Western and early Western music. Such music is generally composed by a process of centonization, either freely (i.e. improvised) or in a fixed pattern.

"Melody type" as used by the ethnomusicologist Mark Slobin (1982 , 186) [3] is defined as a "group of melodies that are related, in that they all contain similar modal procedures and characteristic rhythmic and melodic contours or patterns". [4]

Most cultures which compose music in this way organize the patterns into distinct melody types. These are often compared to modern Western scales, but they in fact represent much more information than a sequence of permissible pitches, since they include how those pitches should function in the music, and indicate basic formulas which serve as a basis for improvisation. In non-improvised music, such as codified liturgical music, it is still usually clear how the melody developed from set patterns.

On one end of the continuum, the right, the melody type is a schema that is quite definite—a specific melody or a tune. When a musician improvises on this schema, he [or she] plays the melody with only slight variations. The basic outline is preserved and is clearly recognized by the listener. The best example ... on this end of the continuum is a folk song. A genuine folk song performance is a kind of improvisation. No one person sings it exactly as it came to him [or her]. One of the challenges of folk song research, of course, is to find all the variants of the tune and to try to trace the family relationships.

On the left side of the continuum is the melody type as a mode. Here the melody type is similar to a church mode: a scalar configuration with a preferential order of tones.

...The closer we get to the pole where a melody type is a tune, the more definite and literal is the schema.— May (1983) [5]

A melodic formula, ranging length from a short motif of a few notes to an entire melody, which is used as the basis for musical compositions. It differs from a mode, which simply sets forth a sequence of intervals (in Western music, half tones and whole tones), and from a scale (the notes of a mode in rising order of pitch), in that it is more specific: a melody type spells out actual sequences of tones, just as they are to appear in a piece, as well as particular beginnings and endings, ornaments, and other details. Melody types are found mostly in the music of ancient peoples—the Greeks, Hebrews, and others—and of Eastern peoples—the Arabs, Persians (Iranians), Indians, and others. For...example... raga.

— Ammer (2004) [6]

In most cases, these melody types are associated with extra-musical implications, particularly emotions (see Indian rasa, for instance). They are also often associated with certain times. For example, most ragas are associated with a certain time of day, or a wayang performance in Java implies a certain succession of pathets.

Many of these traditions have a corresponding rhythmic framework. These include:

In music theory, the term mode or modus is used in a number of distinct senses, depending on context.

Plainsong or plainchant is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text. Plainsong was the exclusive form of Christian church music until the ninth century, and the introduction of polyphony.

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe during the 9th and 10th centuries, with later additions and redactions. Although popular legend credits Pope Gregory I with inventing Gregorian chant, scholars believe that it arose from a later Carolingian synthesis of the Old Roman chant and Gallican chant.

Carnatic music, known as Karnāṭaka saṃgīta or Karnāṭaka saṅgītam in the South Indian languages, is a system of music commonly associated with South India, including the modern Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and Sri Lanka. It is one of two main subgenres of Indian classical music that evolved from ancient Hindu texts and traditions, particularly the Samaveda. The other subgenre being Hindustani music, which emerged as a distinct form because of Persian or Islamic influences from Northern India. The main emphasis in Carnatic music is on vocal music; most compositions are written to be sung, and even when played on instruments, they are meant to be performed in gāyaki (singing) style.

In music, monophony is the simplest of musical textures, consisting of a melody, typically sung by a single singer or played by a single instrument player without accompanying harmony or chords. Many folk songs and traditional songs are monophonic. A melody is also considered to be monophonic if a group of singers sings the same melody together at the unison or with the same melody notes duplicated at the octave. If an entire melody is played by two or more instruments or sung by a choir with a fixed interval, such as a perfect fifth, it is also said to be monophony. The musical texture of a song or musical piece is determined by assessing whether varying components are used, such as an accompaniment part or polyphonic melody lines.

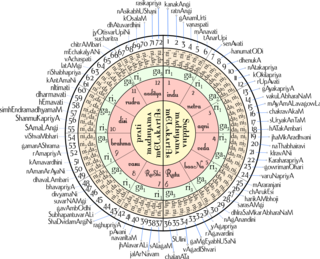

A raga or raag is a melodic framework for improvisation in Indian classical music akin to a melodic mode. The rāga is a unique and central feature of the classical Indian music tradition, and as a result has no direct translation to concepts in classical European music. Each rāga is an array of melodic structures with musical motifs, considered in the Indian tradition to have the ability to "colour the mind" and affect the emotions of the audience.

Indian classical music is the classical music of the Indian subcontinent. It is generally described using terms like Marg Sangeet and Shastriya Sangeet. It has two major traditions: the North Indian classical music known as Hindustani and the South Indian expression known as Carnatic. These traditions were not distinct until about the 15th century. During the period of Mughal rule of the Indian subcontinent, the traditions separated and evolved into distinct forms. Hindustani music emphasizes improvisation and exploration of all aspects of a raga, while Carnatic performances tend to be short composition-based. However, the two systems continue to have more common features than differences.

When speaking of the music of Syria, it is important to remember that there are certain musical traditions and practices that have been present in Syria longer than others. There have been musical influences introduced into Syria through multiple eras of conquest and influences from surrounding cultures in modern-day Syria. Lying near Egypt and Israel, and connected to southern Europe by the Mediterranean, Syria became host to many distinct cultural musics through trade and route. The music present in Syria is related greatly to poetry, influenced greatly by the Bedouin nomadic tribes, the maqam system in Arabic classical music, as well as influenced greatly by the geopolitical movement and conflict in the Middle East. Syrian music generally has a singer who is accompanied by three or four instruments. The texture is usually thin but can become denser depending on the use of each instrument. Music is tightly linked to poetry in Syria.

The Turkish makam is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam specifies a unique intervalic structure and melodic development (seyir). Whether a fixed composition or a spontaneous composition, all attempt to follow the melody type. The rhythmic counterpart of makam in Turkish music is usul.

A neume is the basic element of Western and Eastern systems of musical notation prior to the invention of five-line staff notation.

In chant, a reciting tone can refer to either a repeated musical pitch or to the entire melodic formula for which that pitch is a structural note. In Gregorian chant, the first is also called tenor, dominant or tuba, while the second includes psalm tones as well as simpler formulae for other readings and for prayers.

Echos is the name in Byzantine music theory for a mode within the eight-mode system (oktoechos), each of them ruling several melody types, and it is used in the melodic and rhythmic composition of Byzantine chant, differentiated according to the chant genre and according to the performance style. It is akin to a Western medieval tonus, an Andalusian tab', an Arab naġam, or a Persian parde.

In music centonization is a theory about the composition of a melody, melodies, or piece based on pre-existing melodic figures and formulas. A piece created using centonization is known as a "centonate".

Musical improvisation is the creative activity of immediate musical composition, which combines performance with communication of emotions and instrumental technique as well as spontaneous response to other musicians. Sometimes musical ideas in improvisation are spontaneous, but may be based on chord changes in classical music and many other kinds of music. One definition is a "performance given extempore without planning or preparation". Another definition is to "play or sing (music) extemporaneously, by inventing variations on a melody or creating new melodies, rhythms and harmonies". Encyclopædia Britannica defines it as "the extemporaneous composition or free performance of a musical passage, usually in a manner conforming to certain stylistic norms but unfettered by the prescriptive features of a specific musical text." Improvisation is often done within a pre-existing harmonic framework or chord progression. Improvisation is a major part of some types of 20th-century music, such as blues, rock music, jazz, and jazz fusion, in which instrumental performers improvise solos, melody lines and accompaniment parts.

Ambrosian chant is the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Ambrosian rite of the Roman Catholic Church, related to but distinct from Gregorian chant. It is primarily associated with the Archdiocese of Milan, and named after St. Ambrose much as Gregorian chant is named after Gregory the Great. It is the only surviving plainchant tradition besides the Gregorian to maintain the official sanction of the Roman Catholic Church.

Mozarabic chant is the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Visigothic/Mozarabic rite of the Catholic Church, related to the Gregorian chant. It is primarily associated with Hispania under Visigothic rule and later with the Mozarabs and was replaced by the chant of the Roman rite following the Christian Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Although its original medieval form is largely lost, a few chants have survived with readable musical notation, and the chanted rite was later revived in altered form and continues to be used in a few isolated locations in Spain, primarily in Toledo.

Beneventan chant is a liturgical plainchant repertory of the Roman Catholic Church, used primarily in the orbit of the southern Italian ecclesiastical centers of Benevento and Monte Cassino distinct from Gregorian chant and related to Ambrosian chant. It was officially supplanted by the Gregorian chant of the Roman rite in the 11th century, although a few Beneventan chants of local interest remained in use.

Old Roman chant is the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Roman rite of the early Christian Church. It was formerly performed in Rome, and, although it is closely related to Gregorian chant, the two are distinct. Gregorian Chant gradually supplanted Old Roman Chant between the 11th century and the 13th century AD. Unlike other chant traditions, Old Roman chant and Gregorian chant share essentially the same liturgy and the same texts. Many of their melodies are also closely related. Although primarily associated with the churches of Rome, the Old Roman chant was also performed in parts of central Italy, and it was possibly performed much more widely.

A tonary is a liturgical book in the Western Christian Church which lists by incipit various items of Gregorian chant according to the Gregorian mode (tonus) of their melodies within the eight-mode system. Tonaries often include Office antiphons, the mode of which determines the recitation formula for the accompanying text, but a tonary may also or instead list responsories or Mass chants not associated with formulaic recitation. Although some tonaries are stand-alone works, they were frequently used as an appendix to other liturgical books such as antiphonaries, graduals, tropers, and prosers, and are often included in collections of musical treatises.

Arabic maqam is the system of melodic modes used in traditional Arabic music, which is mainly melodic. The word maqam in Arabic means place, location or position. The Arabic maqam is a melody type. It is "a technique of improvisation" that defines the pitches, patterns, and development of a piece of music and is "unique to Arabian art music". There are 72 heptatonic tone rows or scales of maqamat. These are constructed from major, neutral, and minor seconds. Each maqam is built on a scale, and carries a tradition that defines its habitual phrases, important notes, melodic development and modulation. Both compositions and improvisations in traditional Arabic music are based on the maqam system. Maqamat can be realized with either vocal or instrumental music, and do not include a rhythmic component.