Related Research Articles

Research is "creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge". It involves the collection, organization and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular attentiveness to controlling sources of bias and error. These activities are characterized by accounting and controlling for biases. A research project may be an expansion of past work in the field. To test the validity of instruments, procedures, or experiments, research may replicate elements of prior projects or the project as a whole.

In common usage, evaluation is a systematic determination and assessment of a subject's merit, worth and significance, using criteria governed by a set of standards. It can assist an organization, program, design, project or any other intervention or initiative to assess any aim, realisable concept/proposal, or any alternative, to help in decision-making; or to generate the degree of achievement or value in regard to the aim and objectives and results of any such action that has been completed.

A focus group is a group interview involving a small number of demographically similar participants. Their reactions to specific researcher/evaluator-posed questions are studied. Focus groups are used in market research to understand better people's reactions to products or services or participants' perceptions of shared experiences. The discussions can be guided or open. In market research, focus groups can explore a group's response to a new product or service. As a program evaluation tool, they can elicit lessons learned and recommendations for performance improvement. The idea is for the researcher to understand participants' reactions. If group members are representative of a larger population, those reactions may be expected to reflect the views of that larger population. Thus, focus groups constitute a research or evaluation method that researchers organize to collect qualitative data through interactive and directed discussions.

Cross-cultural communication is a field of study investigating how people from differing cultural backgrounds communicate, in similar and different ways among themselves, and how they endeavor to communicate across cultures. Intercultural communication is a related field of study.

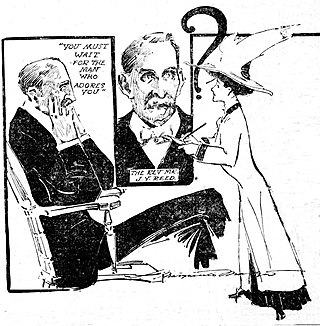

An interview is a structured conversation where one participant asks questions, and the other provides answers. In common parlance, the word "interview" refers to a one-on-one conversation between an interviewer and an interviewee. The interviewer asks questions to which the interviewee responds, usually providing information. That information may be used or provided to other audiences immediately or later. This feature is common to many types of interviews – a job interview or interview with a witness to an event may have no other audience present at the time, but the answers will be later provided to others in the employment or investigative process. An interview may also transfer information in both directions.

Survey methodology is "the study of survey methods". As a field of applied statistics concentrating on human-research surveys, survey methodology studies the sampling of individual units from a population and associated techniques of survey data collection, such as questionnaire construction and methods for improving the number and accuracy of responses to surveys. Survey methodology targets instruments or procedures that ask one or more questions that may or may not be answered.

Qualitative marketing research involves a natural or observational examination of the philosophies that govern consumer behavior. The direction and framework of the research is often revised as new information is gained, allowing the researcher to evaluate issues and subjects in an in-depth manner. The quality of the research produced is heavily dependent on the skills of the researcher and is influenced by researcher bias.

Quantitative marketing research is the application of quantitative research techniques to the field of marketing research. It has roots in both the positivist view of the world, and the modern marketing viewpoint that marketing is an interactive process in which both the buyer and seller reach a satisfying agreement on the "four Ps" of marketing: Product, Price, Place (location) and Promotion.

Qualitative psychological research is psychological research that employs qualitative methods.

Participant observation is one type of data collection method by practitioner-scholars typically used in qualitative research and ethnography. This type of methodology is employed in many disciplines, particularly anthropology, sociology, communication studies, human geography, and social psychology. Its aim is to gain a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals and their practices through an intensive involvement with people in their cultural environment, usually over an extended period of time.

Qualitative research is a type of research that aims to gather and analyse non-numerical (descriptive) data in order to gain an understanding of individuals' social reality, including understanding their attitudes, beliefs, and motivation. This type of research typically involves in-depth interviews, focus groups, or observations in order to collect data that is rich in detail and context. Qualitative research is often used to explore complex phenomena or to gain insight into people's experiences and perspectives on a particular topic. It is particularly useful when researchers want to understand the meaning that people attach to their experiences or when they want to uncover the underlying reasons for people's behavior. Qualitative methods include ethnography, grounded theory, discourse analysis, and interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative research methods have been used in sociology, anthropology, political science, psychology, communication studies, social work, folklore, educational research, information science and software engineering research.

Autoethnography is a form of ethnographic research in which a researcher connects personal experiences to wider cultural, political, and social meanings and understandings. It is considered a form of qualitative and/or arts-based research.

Narrative inquiry or narrative analysis emerged as a discipline from within the broader field of qualitative research in the early 20th century, as evidence exists that this method was used in psychology and sociology. Narrative inquiry uses field texts, such as stories, autobiography, journals, field notes, letters, conversations, interviews, family stories, photos, and life experience, as the units of analysis to research and understand the way people create meaning in their lives as narratives.

A structured interview is a quantitative research method commonly employed in survey research. The aim of this approach is to ensure that each interview is presented with exactly the same questions in the same order. This ensures that answers can be reliably aggregated and that comparisons can be made with confidence between sample sub groups or between different survey periods.

Cognitive pretesting, or cognitive interviewing, is a field research method where data is collected on how the subject answers interview questions. It is the evaluation of a test or questionnaire before it's administered. It allows survey researchers to collect feedback regarding survey responses and is used in evaluating whether the question is measuring the construct the researcher intends. The data collected is then used to adjust problematic questions in the questionnaire before fielding the survey to the full sample of people.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) is a qualitative form of psychology research. IPA has an idiographic focus, which means that instead of producing generalization findings, it aims to offer insights into how a given person, in a given context, makes sense of a given situation. Usually, these situations are of personal significance; examples might include a major life event, or the development of an important relationship. IPA has its theoretical origins in phenomenology and hermeneutics, and many of its key ideas are inspired by the work of Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. IPA's tendency to combine psychological, interpretative, and idiographic elements is what distinguishes it from other approaches to qualitative, phenomenological psychology.

An unstructured interview or non-directive interview is an interview in which questions are not prearranged. These non-directive interviews are considered to be the opposite of a structured interview which offers a set amount of standardized questions. The form of the unstructured interview varies widely, with some questions being prepared in advance in relation to a topic that the researcher or interviewer wishes to cover. They tend to be more informal and free flowing than a structured interview, much like an everyday conversation. Probing is seen to be the part of the research process that differentiates the in-depth, unstructured interview from an everyday conversation. This nature of conversation allows for spontaneity and for questions to develop during the course of the interview, which are based on the interviewees' responses. The chief feature of the unstructured interview is the idea of probe questions that are designed to be as open as possible. It is a qualitative research method and accordingly prioritizes validity and the depth of the interviewees' answers. One of the potential drawbacks is the loss of reliability, thereby making it more difficult to draw patterns among interviewees' responses in comparison to structured interviews. Unstructured interviews are used in a variety of fields and circumstances, ranging from research in social sciences, such as sociology, to college and job interviews. Fontana and Frey have identified three types of in depth, ethnographic, unstructured interviews - oral history, creative interviews, and post-modern interviews.

Evidence-based nursing (EBN) is an approach to making quality decisions and providing nursing care based upon personal clinical expertise in combination with the most current, relevant research available on the topic. This approach is using evidence-based practice (EBP) as a foundation. EBN implements the most up to date methods of providing care, which have been proven through appraisal of high quality studies and statistically significant research findings. The goal of EBN is to improve the health and safety of patients while also providing care in a cost-effective manner to improve the outcomes for both the patient and the healthcare system. EBN is a process founded on the collection, interpretation, appraisal, and integration of valid, clinically significant, and applicable research. The evidence used to change practice or make a clinical decision can be separated into seven levels of evidence that differ in type of study and level of quality. To properly implement EBN, the knowledge of the nurse, the patient's preferences, and multiple studies of evidence must all be collaborated and utilized in order to produce an appropriate solution to the task at hand. These skills are taught in modern nursing education and also as a part of professional training.

Thematic analysis is one of the most common forms of analysis within qualitative research. It emphasizes identifying, analysing and interpreting patterns of meaning within qualitative data. Thematic analysis is often understood as a method or technique in contrast to most other qualitative analytic approaches - such as grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative analysis and interpretative phenomenological analysis - which can be described as methodologies or theoretically informed frameworks for research. Thematic analysis is best thought of as an umbrella term for a variety of different approaches, rather than a singular method. Different versions of thematic analysis are underpinned by different philosophical and conceptual assumptions and are divergent in terms of procedure. Leading thematic analysis proponents, psychologists Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke distinguish between three main types of thematic analysis: coding reliability approaches, code book approaches and reflexive approaches. They describe their own widely used approach first outlined in 2006 in the journal Qualitative Research in Psychology as reflexive thematic analysis. Their 2006 paper has over 120,000 Google Scholar citations and according to Google Scholar is the most cited academic paper published in 2006. The popularity of this paper exemplifies the growing interest in thematic analysis as a distinct method.

An interview in qualitative research is a conversation where questions are asked to elicit information. The interviewer is usually a professional or paid researcher, sometimes trained, who poses questions to the interviewee, in an alternating series of usually brief questions and answers. They can be contrasted with focus groups in which an interviewer questions a group of people and observes the resulting conversation between interviewees, or surveys which are more anonymous and limit respondents to a range of predetermined answer choices. In addition, there are special considerations when interviewing children. In phenomenological or ethnographic research, interviews are used to uncover the meanings of central themes in the life world of the subjects from their own point of view.

References

- Arminio, J., Jones, S., Torres, V. Negotiating the Complexities of Qualitative Research in Higher Education: Fundamental Elements and Issues.

- Barbour, R.S. (2001).Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog. BMJ. 322, 1115–1117.

- Britten, Nicky. BMJ 1995; 311: 251-253 (22 July).

- Bryman, Alan. (Ed.). Member Validation. In Addressing social problems through qualitative research Loughborough: Reference World.

- Bygstad, B., Munkvold B. (2007) "The Significance of Member Validation in Qualitative Analysis: Experiences From a Longitudinal Case Study." Proceedings of the 40th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

- Byrne, M.M. (2001). Evaluating the findings of qualitative research. AORN Journal.

- Cohen, D., Crabtree, B. "Qualitative Research Guidelines Project." July 2006.

- Doyle, S. (2007). Member Checking With Older Women: A Framework for Negotiating Meaning. Healthcare for Women International, 28, 888–908.

- Flick, U. (2006). An Introduction to Qualitative Research. Sage.

- Gordon, C., Prince, M.B., Benkendorf, J.L. (2002). Hamilton HE Journal of Genetic Counseling. 4, 245–63.

- Grinnel R., Unrau Y., (2008) Social Work Research and Evaluation: Foundations of Evidence-based Practice. Oxford University Press US.

- Holloway, I. (2005) Qualitative Research in Healthcare. McGraw-Hill.

- Kirk, J., & Miller, M. L. (1986). Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Lincoln, Y., Guba, E. (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

- LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2006). Nursing Research: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier.

- Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. H. (1984). Analyzing social settings. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc.

- McBrien, Barry. British Journal of Nursing, 2008 Nov 7-20

- Morse, J.M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., and Spiers, J. (2002). Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 1, 2.

- Ratcliff, D. (1995). Notes for Five Part Seminar on Qualitative Research.

- Rubin, A., Babbie, E.R. (2008). Research methods for social work. Belmont, CA:Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Tanggaard, L. (2008). Objections in research interviewing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(3), p 15–29.

- Walters, J. (2006, February). Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook.. Adult Education Quarterly, 56(2), 166–167. Retrieved November 29, 2008, doi : 10.1177/0741713605283440

- Watson, R., Benner, P., & Ketefian, S. (2008). Nursing Research: Designs and Methods. Elsevier Health Sciences.