Related Research Articles

Menopause, also known as the climacteric, is the time when menstrual periods permanently stop, marking the end of reproduction. It typically occurs between the ages of 45 and 55, although the exact timing can vary. Menopause is usually a natural change. It can occur earlier in those who smoke tobacco. Other causes include surgery that removes both ovaries or some types of chemotherapy. At the physiological level, menopause happens because of a decrease in the ovaries' production of the hormones estrogen and progesterone. While typically not needed, a diagnosis of menopause can be confirmed by measuring hormone levels in the blood or urine. Menopause is the opposite of menarche, the time when a girl's periods start.

Prison sexuality consists of sexual relationships between prisoners or between a prisoner and a prison employee or other persons to whom prisoners have access. Since prisons are usually separated by sex, most sexual activity is with a same-sex partner. Exceptions to this include sex with spouses/partners during conjugal visits and sex with a prison employee of the opposite sex.

Incarceration in the United States is one of the primary means of punishment for crime in the United States. In 2023, over five million people are under supervision by the criminal justice system, with nearly two million people incarcerated in state or federal prisons and local jails. The United States has the largest known prison population in the world. Prison populations grew dramatically beginning in the 1970s, but began a decline around 2009, dropping 25% by year-end 2021.

A prison nursery is a section of a prison that houses incarcerated mothers and their very young children. Prison nurseries are not common in correctional facilities in the United States, although prior to the 1950s many states had them and they are widespread throughout the rest of the world.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people face difficulties in prison such as increased vulnerability to sexual assault, other kinds of violence, and trouble accessing necessary medical care. While much of the available data on LGBTQ inmates comes from the United States, Amnesty International maintains records of known incidents internationally in which LGBTQ prisoners and those perceived to be lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender have suffered torture, ill-treatment and violence at the hands of fellow inmates as well as prison officials.

Prison healthcare is the medical specialty in which healthcare providers care for people in prisons and jails. Prison healthcare is a relatively new specialty that developed alongside the adaption of prisons into modern disciplinary institutions. Enclosed prison populations are particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases, including arthritis, asthma, hypertension, cervical cancer, hepatitis, tuberculosis, AIDS, and HIV, and mental health issues, such as Depression, mania, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. These conditions link prison healthcare to issues of public health, preventive healthcare, and hygiene. Prisoner dependency on provided healthcare raises unique problems in medical ethics.

As of 2013, across the world, 625,000 women and children were being incarcerated in correctional facilities, and the female prison population was increasing in all continents. The list of countries by incarceration rate includes a main table with a column for the historical and current percentage of prisoners who are female.

Infectious diseases within American correctional settings are a concern within the public health sector. The corrections population is susceptible to infectious diseases through exposure to blood and other bodily fluids, drug injection, poor health care, prison overcrowding, demographics, security issues, lack of community support for rehabilitation programs, and high-risk behaviors. The spread of infectious diseases, such as HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, hepatitis C (HCV), hepatitis B (HBV), and tuberculosis, result largely from needle-sharing, drug use, and consensual and non-consensual sex among prisoners. HIV and hepatitis C need specific attention because of the specific public health concerns and issues they raise.

Postmenopausal confusion, also commonly referred to as postmenopausal brain fog, is a group of symptoms of menopause in which women report problems with cognition at a higher frequency during postmenopause than before.

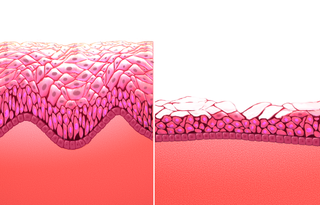

Atrophic vaginitis is inflammation of the vagina as a result of tissue thinning due to not enough estrogen. Symptoms may include pain with sex, vaginal itchiness or dryness, and an urge to urinate or burning with urination. It generally does not resolve without ongoing treatment. Complications may include urinary tract infections.

The incarceration of women in the United States refers to the imprisonment of women in both prisons and jails in the United States. There are approximately 219,000 incarcerated women in the US according to a November 2018 report by the Prison Policy Initiative, and the rate of incarceration of women in the United States is at a historic and global high, with 133 women in correctional facilities per every 100,000 female citizens. The United States is home to just 4% of the world's female population, yet the US is responsible for 33% of the entire world's incarcerated female population. The steep rise in the population of incarcerated women in the US is linked to the complex history of the war on drugs and the US's prison–industrial complex, which lead to mass incarceration among many demographics, but had particularly dramatic impacts on women and especially women of color. However, women made up only 10.4% of the US prison and jail population, as of 2015.

The use of shackles or restraints on pregnant women is a common practice in prisons and jails in the United States. Shackling is defined as "using any physical restraint or mechanical device to control the movement of a prisoner's body or limbs, including handcuffs, leg shackles, and belly chains". For females, shackles or handcuffs are placed around the ankles, wrists, or around the stomach. The shackling of pregnant women occurs while they are transported within a facility, transported to a hospital, and/or during and after childbirth. Restraints are also used on detained pregnant women in immigration detention facilities.

People with mental illnesses are overrepresented in jail and prison populations in the United States relative to the general population. There are three times as many mentally ill people in jails and prisons than in hospitals in the United States. Mentally ill people experience solitary confinement at disproportionate rates compared to the general prison population. There are a number of reasons for this overrepresentation of mentally ill people in jails and prisons, including the deinstitutionalization of mentally ill individuals in the mid-twentieth century, inadequate community treatment resources, and the criminalization of mental illness itself. There is a consensus that mentally ill offenders have comparable rates of recidivism to non-mentally ill offenders.

The Bangkok Rules, or formally, "The United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders", is a set of 70 rules focused on the treatment of female offenders and prisoners adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 22 December 2010. The Bangkok Rules, or the "70 Rules" as it is frequently known, is the first set of rules tailored to the treatment of women prisoners. It supplements existing international standards on the treatment of prisoners, particularly the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, which applies to all prisoners regardless of gender.

Gender-responsive prisons are prisons constructed to provide gender-specific care to incarcerated women. Contemporary sex-based prison programs were presented as a solution to the rapidly increasing number of women in the prison industrial complex and the overcrowding of California's prisons. These programs vary in intent and implementation and are based on the idea that female offenders differ from their male counterparts in their personal histories and pathways to crime. Multi-dimensional programs oriented toward female behaviors are considered by many to be effective in curbing recidivism.

People in prison are more likely than the general United States population to have received a mental disorder diagnosis, and women in prison have higher rates of mental illness and mental health treatment than do men in prison. Furthermore, women in prisons are three times more likely than the general population to report poor physical and mental health. Women are the fastest growing demographic of the United States prison population. As of 2019, there are about 222,500 women incarcerated in state and federal prisons in the United States. Women comprise roughly 8% of all inmates in the United States.

In the United States, prisons are obligated to provide health care to prisoners. Such health care is sometimes called correctional medicine. In women's prisons, correctional medicine includes attention to reproductive health.

Prisoner reentry is the process by which prisoners who have been released return to the community. Many types of programs have been implemented with the goal of reducing recidivism and have been found to be effective for this purpose. Consideration for the conditions of the communities formerly incarcerated individuals are re-entering, which are often disadvantaged, is a fundamental part of successful re-entry.

Alongside the general opioid epidemic in the United States, there has been an increase in the number of incarcerated people in the United States experiencing opioid use disorder. Over half of the estimated 7 million incarcerated people in the United States meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria for substance use disorder, and only 20% receive treatment. To alleviate this problem, the United States Department of Corrections has implemented various treatment plans and programs for inmates.

Menopause in the workplace is a social and human resources campaigning issue in which people work to raise awareness of the impact menopause symptoms can have on attendance and performance in the workplace.

References

- ↑ van den Bergh, Brenda J; Gatherer, Alex; Møller, Lars F (June 2009). "Women's health in prison: urgent need for improvement in gender equity and social justice". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 87 (6): 406. doi:10.2471/BLT.09.066928. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 2686215 . PMID 19565112.

- ↑ Schach, Eliana; Kothari, Jaineel; Perkiss, Evan; Hutchinson-Colas, Juana; Turock, Heather; McGreevey, James; Bachmann, Gloria; NJ Commission on Women's Reentry Health Committee (August 2021). "Symptomatic menopause: Additional challenges for incarcerated women". Maturitas. 150: 37–41. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.05.009. ISSN 1873-4111. PMID 34274074. S2CID 236092185.

- 1 2 3 Jaffe, Elana F.; Palmquist, Aunchalee E. L.; Knittel, Andrea K. (2021-03-11). "Experiences of menopause during incarceration". Menopause. 28 (7): 829–832. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001762. ISSN 1530-0374. PMC 8495613 . PMID 33739317.

- ↑ Barry, Lisa C.; Adams, Kathryn B.; Zaugg, Danielle; Noujaim, Deborah (2020-03-03). "Health-care needs of older women prisoners: Perspectives of the health-care workers who care for them". Journal of Women & Aging. 32 (2): 183–202. doi:10.1080/08952841.2019.1593771. ISSN 0895-2841. PMC 6776728 . PMID 30943874.

- 1 2 "WHO perspective on addressing women's health in prison". www.euro.who.int. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ Riach, Kathleen; Jack, Gavin (2021-10-14). "Women's Health in/and Work: Menopause as an Intersectional Experience". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (20): 10793. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010793 . ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 8536086 . PMID 34682537.

- ↑ Routes (2020-08-14). "Period poverty in prison: an intersectional commentary on the lived experiences of incarcerated women in US prison facilities". Routes. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ Lee, Jean. "5 pads for 2 cellmates: Period inequity remains a problem in prisons". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ "The Period Project: Period Poverty and the Fight for Menstrual Equity - Ms. Magazine". msmagazine.com. 23 February 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ "Perimenopause - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- 1 2 Schoenly, Lorry (2014-01-15). "Caring for Women in Prison: Menopause and Osteoporosis". Essentials of Correctional Nursing. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- 1 2 "UN Bangkok Rules". Penal Reform International. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ "Little known about needs of people who experience menopause while incarcerated". UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. Retrieved 2022-03-06.

- ↑ "Improving the health and wellbeing for women in prison - UK Health Security Agency". ukhsa.blog.gov.uk. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ Hazlegreaves, Steph (2021-10-18). "Menopause: The last great taboo". Open Access Government. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ Public Health England (2018). "Gender Specific Standards to Improve Health and Wellbeing for Women in Prison in England" (PDF). Public Health England.

- ↑ Initiative, Prison Policy. "The Gender Divide: Tracking women's state prison growth". www.prisonpolicy.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Women's Health Care in Correctional Settings". www.ncchc.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ↑ "Women's Policy Framework". GOV.UK. 26 June 2021. Retrieved 2022-03-06.

- ↑ "Conference 'Women's health in Prison' and HIPP Network Meeting". www.euro.who.int. Retrieved 2022-03-06.

- ↑ UNODC (2011). "THE BANGKOK RULES" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)