Minerva is the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. Minerva is not a patron of violence such as Mars, but of strategic war. From the second century BC onward, the Romans equated her with the Greek goddess Athena. Minerva is one of the three Roman deities in the Capitoline Triad, along with Jupiter and Juno.

Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and religion. As the Etruscan civilization was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC, the Etruscan religion and mythology were partially incorporated into ancient Roman culture, following the Roman tendency to absorb some of the local gods and customs of conquered lands. The first attestations of an Etruscan religion can be traced back to the Villanovan culture.

Aita, also spelled Eita, is an epithet of the Etruscan chthonic fire god Śuri as god of the underworld, roughly equivalent to the Greek god Hades.

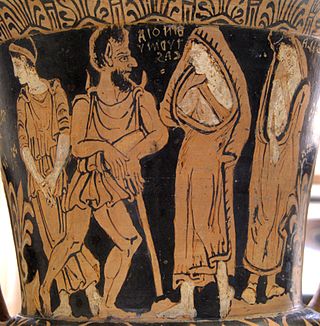

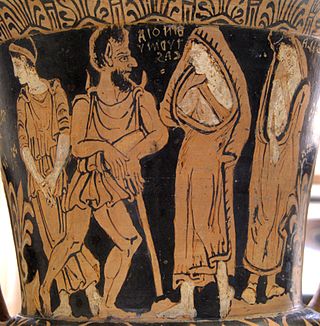

In Etruscan mythology, Charun acted as one of the psychopompoi of the underworld. He is often portrayed with Vanth, a winged figure also associated with the underworld.

In Etruscan religion, Fufluns or Puphluns was a god of plant life, happiness, wine, health, and growth in all things. He is mentioned twice among the gods listed in the inscriptions of the Liver of Piacenza, being listed among the 16 gods that rule the Etruscan astrological houses. He is the 9th of those 16 gods. He is the son of Semla and the god Tinia. He was worshipped at Populonia and is the namesake of that town.

In Etruscan religion and myth, Thalna was a divine figure usually regarded as a goddess of childbirth. Determinate gender, however, is not necessarily a characteristic of Etruscan deities, and Thalna is also either depicted as male, or seems to be identified as a male figure because of the placement of names around a scene. Her other functions include friendship and prophecy. Her name may mean "growth, bloom." She appears in Etruscan art in the company of Turan, Tinia, and Menrva.

Tinia was the god of the sky and the highest god in Etruscan mythology, equivalent to the Roman Jupiter and the Greek Zeus. However, a primary source from the Roman Varro states that Veltha, not Tins, was the supreme deity of the Etruscans. This has led some scholars to conclude that they were assimilated, but this is speculation. He was the husband of Uni and the father of Hercle. Like many other Etruscan deities, his name is gender neutral.

In Etruscan religion, Hercle, the son of Tinia and Uni, was a version of the Greek Heracles, depicted as a muscular figure often carrying a club and wearing a lionskin. He is a popular subject in Etruscan art, particularly bronze mirrors, which show him engaged in adventures not known from the Greek myths of Heracles or the Roman and later classical myths of Hercules.

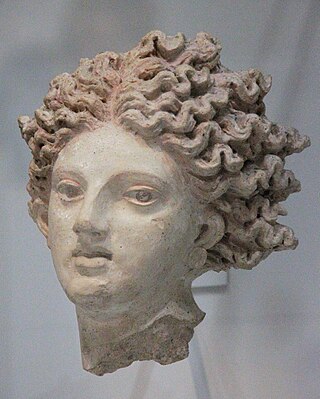

Turan was the Etruscan goddess of love, fertility and vitality and patroness of the city of Velch.

Uni is the ancient goddess of marriage, fertility, family, and women in Etruscan religion and myth, and was the patron goddess of Perugia. She is identified as the Etruscan equivalent of Juno in Roman mythology, and Hera in Greek mythology. As the supreme goddess of the Etruscan pantheon, she is part of the Etruscan trinity, an original precursor to the Capitoline Triad, made up of her husband Tinia, the god of the sky, and daughter Menrva, the goddess of wisdom.

Usil is the Etruscan god of the sun, shown to be identified with Apulu (Apollo). His iconic depiction features Usil rising out of the sea, with a fireball in either outstretched hand, on an engraved Etruscan bronze mirror in late Archaic style, formerly on the Roman antiquities market. On Etruscan mirrors in the Classical style, Usil appears with an aureole.

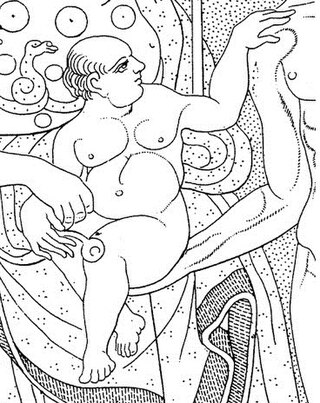

Cel was the Etruscan goddess of the earth. On the Etruscan calendar, the month of Celi (September) is likely named for her. Her Greek counterpart is Gaia and her Roman is Tellus.

Catha is a female Etruscan lunar or solar deity, who may also be connected to childbirth, and has a connection to the underworld. Catha is also the goddess of the south sanctuary at Pyrgi, Italy.

Leinth is an Etruscan deity. Within Etruscan iconography, it is difficult to distinguish mortals from divine figures without inscriptions. Inscriptions to the god Leinth have only been identified on two bronze mirrors and a single fragment of ceramic, found within an artisan’s zone on an Etruscan site in Italy. It is difficult, with such little evidence, to determine what may seem to be even the most rudimentary qualities of the deity, because the Etruscans did not consistently assign specific genders or attributes to their gods. Leinth appears both as a male and a female on two different bronze mirrors, and aside from the inscription, there seem to be no distinguishing traits to connect the figures.

Ethausva is an Etruscan divine figure that appears in a few Etruscan inscriptions. She is depicted as a winged female richly robed and wearing a jeweled crown on her head. Her lack of mention on Etruscan artwork and inscriptions suggest that she was not very common, but she was considered canon to the Etruscan Pantheon so she was still known during the time of the Etruscans.

Epiur is an Etruscan mythological figure that appears on bronze Etruscan engraved mirrors. He is shown as an infant that has the face of a young man. He is also often winged and being held by Hercle or Menrva, who are charged with the protection and care of infants. He is also often shown to be presented to other gods.

Apulu, also syncopated as Aplu, is an epithet of the Etruscan fire god Śuri as chthonic sky god, roughly equivalent to the Greco-Roman god Apollo. Their names are associated on Pyrgi inscriptions too. The name Apulu or Aplu did not come directly from Greece but via a Latin center, probably Palestrina.

Śuri, later latinized as Soranus, was an ancient Etruscan deity, also venerated by other populations of central Italy and later adopted into ancient Roman religion.