Hippocrates of Kos, also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referred to as the "Father of Medicine" in recognition of his lasting contributions to the field, such as the use of prognosis and clinical observation, the systematic categorization of diseases, or the formulation of humoral theory. The Hippocratic school of medicine revolutionized ancient Greek medicine, establishing it as a discipline distinct from other fields with which it had traditionally been associated, thus establishing medicine as a profession.

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real. Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features. Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavior that is inappropriate for a given situation. There may also be sleep problems, social withdrawal, lack of motivation, and difficulties carrying out daily activities. Psychosis can have serious adverse outcomes.

Insanity, madness, lunacy, and craziness are behaviors performed by certain abnormal mental or behavioral patterns. Insanity can manifest as violations of societal norms, including a person or persons becoming a danger to themselves or to other people. Conceptually, mental insanity also is associated with the biological phenomenon of contagion as in the case of copycat suicides. In contemporary usage, the term insanity is an informal, un-scientific term denoting "mental instability"; thus, the term insanity defense is the legal definition of mental instability. In medicine, the general term psychosis is used to include the presence of delusions and/or hallucinations in a patient; and psychiatric illness is "psychopathology", not mental insanity.

Hypochondriasis or hypochondria is a condition in which a person is excessively and unduly worried about having a serious illness. Hypochondria is an old concept whose meaning has repeatedly changed over its lifespan. It has been claimed that this debilitating condition results from an inaccurate perception of the condition of body or mind despite the absence of an actual medical diagnosis. An individual with hypochondriasis is known as a hypochondriac. Hypochondriacs become unduly alarmed about any physical or psychological symptoms they detect, no matter how minor the symptom may be, and are convinced that they have, or are about to be diagnosed with, a serious illness.

Hysteria is a term used colloquially to mean ungovernable emotional excess and can refer to a temporary state of mind or emotion. In the nineteenth century, female hysteria was considered a diagnosable physical illness in women. It is assumed that the basis for diagnosis operated under the belief that women are predisposed to mental and behavioral conditions; an interpretation of sex-related differences in stress responses. In the twentieth century, it shifted to being considered a mental illness. Many influential people such as Sigmund Freud and Jean-Martin Charcot dedicated research to hysteria patients.

Abnormal psychology is the branch of psychology that studies unusual patterns of behavior, emotion, and thought, which could possibly be understood as a mental disorder. Although many behaviors could be considered as abnormal, this branch of psychology typically deals with behavior in a clinical context. There is a long history of attempts to understand and control behavior deemed to be aberrant or deviant, and there is often cultural variation in the approach taken. The field of abnormal psychology identifies multiple causes for different conditions, employing diverse theories from the general field of psychology and elsewhere, and much still hinges on what exactly is meant by "abnormal". There has traditionally been a divide between psychological and biological explanations, reflecting a philosophical dualism in regard to the mind-body problem. There have also been different approaches in trying to classify mental disorders. Abnormal includes three different categories; they are subnormal, supernormal and paranormal.

Historically, mental disorders have had three major explanations, namely, the supernatural, biological and psychological models. For much of recorded history, deviant behavior has been considered supernatural and a reflection of the battle between good and evil. When confronted with unexplainable, irrational behavior and by suffering and upheaval, people have perceived evil. In fact, in the Persian Empire from 550 to 330 B.C., all physical and mental disorders were considered the work of the devil. Physical causes of mental disorders have been sought in history. Hippocrates was important in this tradition as he identified syphilis as a disease and was, therefore, an early proponent of the idea that psychological disorders are biologically caused. This was a precursor to modern psycho-social treatment approaches to the causation of psychopathology, with the focus on psychological, social and cultural factors. Well known philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, etc., wrote about the importance of fantasies, dreams, and thus anticipated, to some extent, the fields of psychoanalytic thought and cognitive science that were later developed. They were also some of the first to advocate for humane and responsible care for individuals with psychological disturbances.

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

The Hippocratic Corpus, or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus covers many diverse aspects of medicine, from Hippocrates' medical theories to what he devised to be ethical means of medical practice, to addressing various illnesses. Even though it is considered a singular corpus that represents Hippocratic medicine, they vary in content, age, style, methods, and views practiced; therefore, authorship is largely unknown. Hippocrates began Western society's development of medicine, through a delicate blending of the art of healing and scientific observations. What Hippocrates was sharing from within his collection of works was not only how to identify symptoms of disease and proper diagnostic practices, but more essentially, he was alluding to his personable form of art, "The art of true living and the art of fine medicine combined." The Hippocratic Corpus became the foundation upon which Western medical practice was built.

Psychopathology is the study of abnormal cognition, behaviour, and experiences which differs according to social norms and rests upon a number of constructs that are deemed to be the social norm at any particular era.

The treatise On Ancient Medicine is perhaps the most intriguing and compelling work of the Hippocratic Corpus. The Corpus itself is a collection of about sixty writings covering all areas of medical thought and practice. Traditionally associated with Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, philological evidence now suggests that it was written over a period of several centuries and stylistically seems to indicate that it was the product of many authors dating from about 450–400 B.C.

Asclepiades, sometimes called Asclepiades of Bithynia or Asclepiades of Prusa, was a Greek physician born at Prusias-on-Sea in Bithynia in Anatolia and who flourished at Rome, where he practised and taught Greek medicine. He attempted to build a new theory of disease, based on the flow of atoms through pores in the body. His treatments sought to restore harmony through the use of diet, exercise, and bathing.

Female hysteria was once a common medical diagnosis for women, which was described as exhibiting a wide array of symptoms, including anxiety, shortness of breath, fainting, nervousness, sexual desire, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in the abdomen, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, (paradoxically) sexually forward behavior, and a "tendency to cause trouble for others". It is no longer recognized by medical authorities as a medical disorder. Its diagnosis and treatment were routine for hundreds of years in Western Europe.

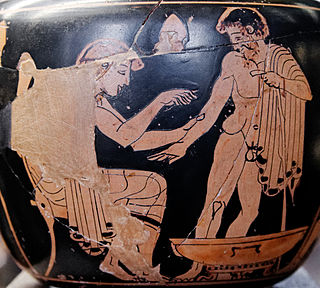

Ancient Greek medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. The Greek term for medicine was iatrikē. Many components were considered in ancient Greek medicine, intertwining the spiritual with the physical. Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed health was affected by the humors, geographic location, social class, diet, trauma, beliefs, and mindset. Early on the ancient Greeks believed that illnesses were "divine punishments" and that healing was a "gift from the Gods". As trials continued wherein theories were tested against symptoms and results, the pure spiritual beliefs regarding "punishments" and "gifts" were replaced with a foundation based in the physical, i.e., cause and effect.

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of deleterious mental conditions. These include various matters related to mood, behaviour, cognition, and perceptions.

Folie à deux, additionally known as shared psychosis or shared delusional disorder (SDD), is a rare psychiatric syndrome in which symptoms of a delusional belief, and sometimes hallucinations, are transmitted from one individual to another. The same syndrome shared by more than two people may be called folie à trois ('three') or quatre ('four'); and further, folie en famille or even folie à plusieurs.

The history of medical diagnosis began in earnest from the days of Imhotep in ancient Egypt and Hippocrates in ancient Greece but is far from perfect despite the enormous bounty of information made available by medical research including the sequencing of the human genome. The practice of diagnosis continues to be dominated by theories set down in the early 20th century.

Modern understanding of disease is very different from the way it was understood in ancient Greece and Rome. The way modern physicians approach healing of the sick differs greatly from the methods used by early general healers or elite physicians like Hippocrates or Galen. In modern medicine, the understanding of disease stems from the "germ theory of disease", a concept that emerged in the second half of the 19th century, such that a disease is the result of an invasion of a micro-organism into a living host. Therefore, when a person becomes ill, modern treatments "target" the specific pathogen or bacterium in order to "beat" or "kill" the disease.

In ancient Rome, mental illness was thought to have been caused by divine punishment, demonic spirits, or an imbalance in the four humors. Ancient Roman doctors noticed patients with conditions similar to anxiety disorders, mood disorders, dyslexia, schizophrenia, speech disorders, among others. Anxiety was treated with Stoic practices similar to modern cognitive behavioral therapy, such as focusing on the present or analyzing the possible outcomes of a situation. Risk factors for mood disorders such as Bipolar disorder were thought to have been alcohol abuse, hypersexuality, aggression, and extreme emotions. Treatments included applying cool substances to the patient's head. People with intellectual disabilities were looked down upon, and they lacked legal protections. However, they could still function as laborers. People with possible schizophrenia were described by ancient Roman doctors and physicians, although they may have been describing mania instead of schizophrenia. Ancient doctors wrote that they should be treated with philosophy, intellectual activities, vomiting, leeching, bloodletting, and venipuncture.