Related Research Articles

The term deconstruction refers to approaches to understanding the relationship between text and meaning. It was introduced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida, who defined it as a turn away from Platonism's ideas of "true" forms and essences which take precedence over appearances, instead considering the constantly changing complex function of language, making static and idealist ideas of it inadequate. Deconstruction instead places emphasis on the mere appearance of language in both speech and writing, or suggests at least that essence as it is called is to be found in its appearance, while it itself is "undecidable", and everyday experiences cannot be empirically evaluated to find the actuality of language.

Immanuel Kant was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics have made him one of the most influential figures in modern Western philosophy.

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from human perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ideas. Idealist perspectives are in two categories: subjective idealism, which proposes that a material object exists only to the extent that a human being perceives the object; and objective idealism, which proposes the existence of an objective consciousness that exists prior to and independently of human consciousness, thus the existence of the object is independent of human perception.

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are often compared with other types of figurative language, such as antithesis, hyperbole, metonymy, and simile. One of the most commonly cited examples of a metaphor in English literature comes from the "All the world's a stage" monologue from As You Like It:

Postmodern philosophy is a philosophical movement that arose in the second half of the 20th century as a critical response to assumptions allegedly present in modernist philosophical ideas regarding culture, identity, history, or language that were developed during the 18th-century Enlightenment. Postmodernist thinkers developed concepts like difference, repetition, trace, and hyperreality to subvert "grand narratives", univocity of being, and epistemic certainty. Postmodern philosophy questions the importance of power relationships, personalization, and discourse in the "construction" of truth and world views. Many postmodernists appear to deny that an objective reality exists, and appear to deny that there are objective moral values.

George Philip Lakoff is an American cognitive linguist and philosopher, best known for his thesis that people's lives are significantly influenced by the conceptual metaphors they use to explain complex phenomena.

In cognitive linguistics, conceptual metaphor, or cognitive metaphor, refers to the understanding of one idea, or conceptual domain, in terms of another. An example of this is the understanding of quantity in terms of directionality or the understanding of time in terms of money.

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary politics of the Enlightenment. The best-known thinkers in the movement, besides Kant, were Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Arthur Schopenhauer, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and the proponents of Jena Romanticism. August Ludwig Hülsen, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, Gottlob Ernst Schulze, Karl Leonhard Reinhold, Salomon Maimon and Friedrich Schleiermacher also made major contributions.

Continental philosophy is a term used to describe some philosophers and philosophical traditions that do not fall under the umbrella of analytic philosophy. However, there is no academic consensus on the definition of continental philosophy. Prior to the twentieth century, the term "continental" was used broadly to refer to philosophy from continental Europe. A different use of the term originated among English-speaking philosophers in the second half of the 20th century, who used it to refer to a range of thinkers and traditions outside the analytic movement. Continental philosophy includes German idealism, phenomenology, existentialism, hermeneutics, structuralism, post-structuralism, deconstruction, French feminism, psychoanalytic theory, and the critical theory of the Frankfurt School as well as branches of Freudian, Hegelian and Western Marxist views.

Jean Paul Gustave Ricœur was a French philosopher best known for combining phenomenological description with hermeneutics. As such, his thought is within the same tradition as other major hermeneutic phenomenologists, Martin Heidegger, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Gabriel Marcel. In 2000, he was awarded the Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy for having "revolutionized the methods of hermeneutic phenomenology, expanding the study of textual interpretation to include the broad yet concrete domains of mythology, biblical exegesis, psychoanalysis, theory of metaphor, and narrative theory."

The Critique of Judgment, also translated as the Critique of the Power of Judgment, is a 1790 book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Sometimes referred to as the "third critique," the Critique of Judgment follows the Critique of Pure Reason (1781) and the Critique of Practical Reason (1788).

Différance is a French term coined by Jacques Derrida. It is a central concept in Derrida's deconstruction, a critical outlook concerned with the relationship between text and meaning. The term différance means "difference and deferral of meaning."

Subjectivity in a philosophical context has to do with a lack of objective reality. Subjectivity has been given various and ambiguous definitions by differing sources as it is not often the focal point of philosophical discourse. However, it is related to ideas of consciousness, agency, personhood, philosophy of mind, reality, and truth. Three common definitions include that subjectivity is the quality or condition of:

Neopragmatism, sometimes called post-Deweyan pragmatism, linguistic pragmatism, or analytic pragmatism, is the philosophical tradition that infers that the meaning of words is a result of how they are used, rather than the objects they represent.

Difference is a key concept of philosophy, denoting the process or set of properties by which one entity is distinguished from another within a relational field or a given conceptual system. In the Western philosophical system, difference is traditionally viewed as being opposed to identity, following the Principles of Leibniz, and in particular, his Law of the identity of indiscernibles. In structuralist and poststructuralist accounts, however, difference is understood to be constitutive of both meaning and identity. In other words, because identity is viewed in non-essentialist terms as a construct, and because constructs only produce meaning through the interplay of differences, it is the case that for both structuralism and poststructuralism, identity cannot be said to exist without difference.

Kantian ethics refers to a deontological ethical theory developed by German philosopher Immanuel Kant that is based on the notion that: "It is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or indeed even beyond it, that could be considered good without limitation except a good will." The theory was developed in the context of Enlightenment rationalism. It states that an action can only be moral if (i) it is motivated by a sense of duty and (ii) its maxim may be rationally willed a universal, objective law.

Indeterminacy, in philosophy, can refer both to common scientific and mathematical concepts of uncertainty and their implications and to another kind of indeterminacy deriving from the nature of definition or meaning. It is related to deconstructionism and to Nietzsche's criticism of the Kantian noumenon.

Trace is one of the most important concepts in Derridian deconstruction. In the 1960s, Jacques Derrida used this concept in two of his early books, namely Writing and Difference and Of Grammatology.

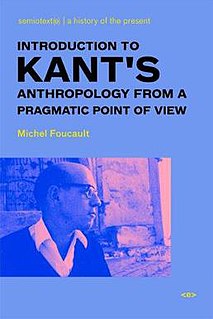

Introduction to Kant's Anthropology is an introductory essay to Michel Foucault's translation of Immanuel Kant's 1798 book Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View — a textbook deriving from lectures he delivered annually between 1772/73 and 1795/96. Both works together served as his secondary thesis, although Foucault's translation of the Anthropology was published separately by Vrin in 1964. The introduction was published in an English translation by Arianna Bove on generation-online.org in 2003.

Critique of the Schopenhaurian philosophy is a literary work by Philipp Mainländer appended to Die Philosophie der Erlösung, offering a criticism of the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. Mainländer saw the purification of Schopenhauer's philosophy as the primary task of his life. The criticism had an important impact on Nietzsche's philosophical development.

References

- Black, M. (1962), Models and Metaphors, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Black, M. (1979), "More about metaphor", in Ortony, A. (ed.), Metaphor and Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cazeaux, C. (2007), Metaphor and Continental Philosophy: From Kant to Derrida, New York: Routledge.

- Davidson, D. (1984), "What metaphors mean", Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kant, I. (1929), Critique of Pure Reason, trans. N. Kemp Smith. London: Macmillan. Original A edition published 1781, B edition 1787.

- Nietzsche, F. (2000), "On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense", in Cazeaux, C. (ed.), The Continental Aesthetics Reader, London: Routledge.

- Ricoeur, P. (1975), La métaphore vive, Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Ricoeur, P. (1977), The Rule of Metaphor: Multi-Disciplinary Studies in the Creation of Meaning in Language, trans. R. Czerny with K. McLaughlin and J. Costello. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Stellardi, G. (2000), Heidegger and Derrida on Philosophy and Metaphor, Amherst, New York: Humanity Books.