Related Research Articles

An assault is the illegal act of causing physical harm or unwanted physical contact to another person, or, in some legal definitions, the threat or attempt to do so. It is both a crime and a tort and, therefore, may result in criminal prosecution, civil liability, or both. Additionally, assault is a criminal act in which a person intentionally causes fear of physical harm or offensive contact to another person. Assault can be committed with or without a weapon and can range from physical violence to threats of violence. Assault is frequently referred to as an attempt to commit battery, which is the deliberate use of physical force against another person. The deliberate inflicting of fear, apprehension, or terror is another definition of assault that can be found in several legal systems. Depending on the severity of the offense, assault may result in a fine, imprisonment, or even death.

Victimology is the study of victimization, including the psychological effects on victims, the relationship between victims and offenders, the interactions between victims and the criminal justice system—that is, the police and courts, and corrections officials—and the connections between victims and other social groups and institutions, such as the media, businesses, and social movements.

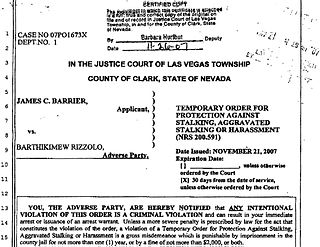

A restraining order or protective order, is an order used by a court to protect a person in a situation involving alleged domestic violence, child abuse, assault, harassment, stalking, or sexual assault.

Articles related to criminology and law enforcement.

Mandatory sentencing requires that offenders serve a predefined term of imprisonment for certain crimes, commonly serious or violent offenses. Judges are bound by law; these sentences are produced through the legislature, not the judicial system. They are instituted to expedite the sentencing process and limit the possibility of irregularity of outcomes due to judicial discretion. Mandatory sentences are typically given to people who are convicted of certain serious and/or violent crimes, and require a prison sentence. Mandatory sentencing laws vary across nations; they are more prevalent in common law jurisdictions because civil law jurisdictions usually prescribe minimum and maximum sentences for every type of crime in explicit laws.

In the United States, the relationship between race and crime has been a topic of public controversy and scholarly debate for more than a century. Crime rates vary significantly between racial groups. Academic research indicates that the over-representation of some racial minorities in the criminal justice system can in part be explained by socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, exposure to poor neighborhoods, poor access to public and early education, and exposure to harmful chemicals and pollution. Racial housing segregation has also been linked to racial disparities in crime rates, as Blacks have historically and to the present been prevented from moving into prosperous low-crime areas through actions of the government and private actors. Various explanations within criminology have been proposed for racial disparities in crime rates, including conflict theory, strain theory, general strain theory, social disorganization theory, macrostructural opportunity theory, social control theory, and subcultural theory.

Sex differences in crime are differences between men and women as the perpetrators or victims of crime. Such studies may belong to fields such as criminology, sociobiology, or feminist studies. Despite the difficulty of interpreting them, crime statistics may provide a way to investigate such a relationship from a gender differences perspective. An observable difference in crime rates between men and women might be due to social and cultural factors, crimes going unreported, or to biological factors for example, testosterone or sociobiological theories). The nature of the crime itself may also require consideration as a factor.

Operation Ceasefire (also known as the Boston Gun Project and the Boston Miracle) is a problem-oriented policing initiative implemented in 1996 in Boston, Massachusetts. The program was specifically aimed at youth gun violence as a large-scale problem. The plan is based on the work of criminologist David M. Kennedy.

Domestic violence is violence or other abuse that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage or cohabitation. Domestic violence is often used as a synonym for intimate partner violence, which is committed by one of the people in an intimate relationship against the other person, and can take place in relationships or between former spouses or partners. In its broadest sense, domestic violence also involves violence against children, parents, or the elderly. It can assume multiple forms, including physical, verbal, emotional, economic, religious, reproductive, or sexual abuse. It can range from subtle, coercive forms to marital rape and other violent physical abuse, such as choking, beating, female genital mutilation, and acid throwing that may result in disfigurement or death, and includes the use of technology to harass, control, monitor, stalk or hack. Domestic murder includes stoning, bride burning, honor killing, and dowry death, which sometimes involves non-cohabitating family members. In 2015, the United Kingdom's Home Office widened the definition of domestic violence to include coercive control.

Lawrence W. Sherman is an American experimental criminologist and police educator who is the founder of evidence-based policing.

Specialized domestic violence courts are designed to improve victim safety and enhance defendant accountability. There is no one set definition of a specialized violence court, although these types of courts can be either civil or criminal and typically hear the majority of an area's domestic violence cases on a separate calendar. Additionally, these courts are typically led by specially assigned judges who can make more informed and consistent decisions based on their expertise and experience with the unique legal and personal issues in domestic violence cases.

Hawaii's Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE) is an intensive supervision program that aims to reduce crime and drug use while saving taxpayers' dollars spent on jail and prison costs. HOPE deals with offenders who have been identified as likely to violate the conditions of their probation or community supervision.

David M. Kennedy is a criminologist, professor, action researcher, and author specializing in crime prevention among inner city gangs, especially in the prevention of violent acts among street gangs. Kennedy developed the Operation Ceasefire group violence intervention in Boston in the 1990s and the High Point Model drug market intervention in High Point, North Carolina, in 2003, which have proven to reduce violence and eliminate overt drug markets in jurisdictions around the United States. He founded the National Network for Safe Communities in 2009 to support cities using these and related strategies.

Domestic violence in United States is a form of violence that occurs within a domestic relationship. Although domestic violence often occurs between partners in the context of an intimate relationship, it may also describe other household violence, such as violence against a child, by a child against a parent or violence between siblings in the same household. It is recognized as an important social problem by governmental and non-governmental agencies, and various Violence Against Women Acts have been passed by the US Congress in an attempt to stem this tide.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to domestic violence:

Prosecution of gender-targeted crimes is the legal proceedings to prosecute crimes such as rape and domestic violence. The earliest documented prosecution of gender-based/targeted crimes is from 1474 when Sir Peter von Hagenbach was convicted for rapes committed by his troops. However, the trial was only successful in indicting Sir von Hagenbach with the charge of rape because the war in which the rapes occurred was "undeclared" and thus the rapes were considered illegal only because of this. Gender-targeted crimes continued to be prosecuted, but it was not until after World War II when an international criminal tribunal – the International Military Tribunal for the Far East – were officers charged for being responsible of the gender-targeted crimes and other crimes against humanity. Despite the various rape charges, the Charter of the Tokyo Tribunal did not make references to rape, and rape was considered as subordinate to other war crimes. This is also the situation for other tribunals that followed, but with the establishments of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), there was more attention to the prosecution of gender-targeted crimes with each of the statutes explicitly referring to rape and other forms of gender-targeted violence.

The management of domestic violence deals with the treatment of victims of domestic violence and preventing repetitions of such violence. The response to domestic violence in Western countries is typically a combined effort between law enforcement, social services, and health care. The role of each has evolved as domestic violence has been brought more into public view.

Experimental criminology is a field within criminology that uses scientific experiments to answer questions about crime: its prevention, punishment and harm. These experiments are primarily conducted in real-life settings, rather than in laboratories. From policing to prosecution to probation, prisons and parole, these field experiments compare similar units with different practices for dealing with crime and responses to crime. These units can be individual suspects or offenders, people, places, neighborhoods, times of day, gangs, or even police officers or judges. The experiments often use random assignment to create similar units in both a "treatment" and a "control" group, with the "control" sometimes consisting of the current way of dealing with crime and the "treatment" a new way of doing so. Such experiments, while not perfect, are generally considered to be the best available way to estimate the cause and effect relationship of one variable to another. Other research designs not using random assignment are also considered to be experiments because they entail human manipulation of the causal relationships being tested.

The National Network for Safe Communities (NNSC) is a research center at City University of New York John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The NNSC works with communities to reduce violence, minimize arrest and incarceration, and increase trust between law enforcement and the public. Working in partnership with cities around the country the NNSC provides advising on implementing evidence-based violence reduction strategies. Additionally, the NNSC provides guidance on how to build trust between law enforcement and the communities it serves, facilitates connections between practitioners within and across jurisdictions, and serves as a resource for knowledge about violence prevention and reduction strategies.

Domestic violence in South Korea is the mental, physical, verbal or sexual abuses or crimes of violence committed towards a victim in a domestic setting of marital relations and cohabitation. Domestic violence describes violence towards a domestic partner, towards children and between siblings. According to the Domestic Violence Survey of South Korea in 2010, elder abuse was estimated to be 10%, physical abuse accounted for 2.2%, emotional abuse 9%, economic abuse 1.2%, and neglect 2.5%. Marital violence has been the most prevalent form of family violence in South Korea. One out of six couples in South Korea had more than one episode of physical violence from their spouse.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sherman, Lawrence W. & Richard A. Berk (April 1984). "The Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment" (PDF). Police Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Buzawa, E. S. & C. G. Buzawa (1990). Domestic Violence: The Criminal Justice Response. Sage. pp. 94–99. ISBN 978-0-7619-2448-7.

- 1 2 Fagan, Jeffrey (1995). "Criminalization of Domestic Violence: Promises and Limits" (PDF). Research Report. Conference on Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation. National Institute of Justice.

- ↑ International Association of Chiefs of Police (1967). Training Key 16: Handling Disturbance Calls. International Association of Chiefs of Police.

- ↑ Parnas, Raymond I. (1967). "The Police Response to the Domestic Disturbance". Wisconsin Law Review. 31: 914–960.

- ↑ Buzawa, Eve S. & Carl G. Buzawa (2005). "Traditional and Innovative Police Responses to Domestic Violence". In Dunham, Roger G. & Geoffrey P. Albert (eds.). Critical Issues in Policing (5th ed.). Waveland Press. ISBN 978-1-57766-352-2.

- 1 2 3 4 LeMoyne, James (April 15, 1984). "A Firmer Response to Family Strife". The New York Times.

- ↑ Straus, M., Gelles, R., & Steinmetz, S. (1980). Behind Closed Doors: Violence in the American Family. Anchor/Doubleday.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Police Foundation (1976). "Domestic Violence and the Police: Studies in Detroit and Kansas City". The Police Foundation.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Gelles, Richard J. (May–June 1993). "Constraints against family violence: how well do they work?". American Behavioral Scientist. 36 (5): 575–587. doi:10.1177/0002764293036005003. S2CID 72484358.

- ↑ Straus (1980), and references below, "Criticism of police response"

- ↑ "AEC Presidents: Lawrence W. Sherman". Academy of Experimental Criminologists. Archived from the original on 2007-06-02. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Elliott, Delbert S. (1989). "Criminal Justice Procedures in Family Violence Crimes". Crime and Justice. University of Chicago Press. 11: 427–480. doi:10.1086/449159. ISSN 0192-3234. S2CID 143627683.

- ↑ "Arrest May Be Deterrent In Domestic Violence, Study Shows". Associated Press / New York Times. May 30, 1984.

- 1 2 3 Schmidt, Janell D. & Lawrence W. Sherman (1993). "Does Arrest Deter Domestic Violence?". American Behavioral Scientist. 36 (5): 601–609. doi:10.1177/0002764293036005005. S2CID 72693516.

- ↑ Hoctor, M. (1997). "Domestic Violence as a Crime against the State". California Law Review. 85 (3): 643–700. doi:10.2307/3481154. JSTOR 3481154.

- ↑ Carswell, Sue (December 2006). "Historical development of the pro-arrest policy in". Family violence and the pro-arrest policy: a literature review. New Zealand Ministry of Justice.

- ↑ Violence Against Women Act of 1994, Archived 2008-09-18 at the Wayback Machine , "The Library of Congress", 1994

- ↑ Clute, Penelope D., “Know the Law: Domestic Violence Mandatory Arrest”

- 1 2 National Institute of Justice, “Table 1: States With Mandatory Arrest” [ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Hoctor, Machaela, “Domestic Violence as a Crime Against the State”, "California Law Review", May 1997

- ↑ Martin, Margaret E. (1997). "Double Your Trouble: Dual Arrest in Family Violence". Journal of Family Violence. 12 (2): 139–157. doi:10.1023/A:1022832610728. S2CID 26295776.

- 1 2 National Institute of Justice, “Domestic Violence Cases: What Research Shows about Arrest and Dual Arrest Rates”, "Office of Justice Programs"

- ↑ Wisconsin Coalition Against Domestic Violence, “Mandatory Arrest Checklist”, Published 1989, Updated 2008, Sec. 968.075, Wis. Stats

- ↑ National Institute of Justice, 1: Arrests by Victim-Offender Relationship: Intimate Partners”, "Office of Justice Programs"

- ↑ Fagan, Jeffrey (1989). "Cessation of Family Violence: Deterrence and Dissuasion". Crime and Justice. 11: 377–425. doi:10.1086/449158. S2CID 144436807.

- ↑ Berk, Richard A. (1993). "What the Scientific Evidence Shows: On the Average, We Can Do No Better Than Arrest". In Gelles, Richard J.; Donileen R. Loseke (eds.). Current Controversies on Family Violence . Sage Publications. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-8039-4674-3.

- ↑ Davis, Richard L. (1998). Domestic Violence: Facts and Fallacies. Praeger. p. 28.

- ↑ Fagan, Jeffrey (1996). "The Criminalization of Domestic Violence: Promises and Limits". National Institute of Justice.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Weisz, Arlene (November 2001). Spousal assault replication program: studies of effects of arrest on domestic violence. National Electronic Network on Violence Against Women. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-31. Pdf. Archived 2015-03-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Garner, Joel H.; Maxwell, Christopher D. (September 2000). "What are the lessons of the police arrest studies?". Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma . 4 (1): 83–114. doi:10.1300/J146v04n01_05. S2CID 145121462.

- ↑ Garner, Joel H.; Maxwell, Christopher D.; Fagan, Jeffrey (March 1995). "Published findings from the spouse assault replication program: a critical review" (PDF). Journal of Quantitative Criminology . 11 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1007/BF02221298. hdl: 2027.42/45108 . S2CID 44371373. Pdf.

- ↑ (5 articles)

- Berk, Richard A.; Campbell, Alec; Klap, Ruth; Western, Bruce (Spring 1992). "A Bayesian analysis of the Colorado Springs spouse abuse experiment". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology . 83 (1): 170–200. doi:10.2307/1143828. JSTOR 1143828. Pdf.

- Dunford, Franklyn W.; Huizinga, David; Elliott, Delbert S. (May 1990). "The role of arrest in domestic assault: the Omaha experiment". Criminology . 28 (2): 183–206. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1990.tb01323.x.

- Hirschel, J. David; Hutchison, III, Ira W.; Dean, Charles W. (February 1992). "The failure of arrest to deter spouse abuse". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency . 29 (1): 7–33. doi:10.1177/0022427892029001002. S2CID 145509246.

- Pate, Anthony; Hamilton, Edwin E. (October 1992). "Formal and informal deterrents to domestic violence: the Dade County spouse assault experiment". American Sociological Review . 57 (5): 691–697. doi:10.2307/2095922. JSTOR 2095922.

- Sherman, Lawrence W.; Schmidt, Janell D.; Rogan, Dennis P.; Gartin, Patrick; Cohen, Ellen G.; Collins, Dean J.; Bacich, Anthony R. (November 1991). "From initial deterrence to long-term escalation: short custody arrest for poverty ghetto domestic violence". Criminology . 29 (4): 821–850. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1991.tb01089.x.

- ↑ Sherman, Lawrence W. (1992). Policing domestic violence: experiments and dilemmas. Janell D. Schmidt and Dennis P. Rogan (contributors). New York Toronto New York: Free Press Maxwell Macmillan Canada Maxwell Macmillan International. ISBN 9780029287316.

- ↑ Sugarman, David B.; Boney-McCoy, Sue (September 2000). "Research synthesis in family violence: the art of reviewing research". Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma . 4 (1): 55–82. doi:10.1300/J146v04n01_04. S2CID 144215380.

- ↑ Maxwell, Christopher D.; Garner, Joel H.; Fagan, Jeffrey (November 2002). "The preventive effects of arrest on intimate partner violence: research, policy and theory". Criminology & Public Policy . 2 (1): 51–80. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2002.tb00107.x. Pdf.