Satisficing is a decision-making strategy or cognitive heuristic that entails searching through the available alternatives until an acceptability threshold is met. The term satisficing, a portmanteau of satisfy and suffice, was introduced by Herbert A. Simon in 1956, although the concept was first posited in his 1947 book Administrative Behavior. Simon used satisficing to explain the behavior of decision makers under circumstances in which an optimal solution cannot be determined. He maintained that many natural problems are characterized by computational intractability or a lack of information, both of which preclude the use of mathematical optimization procedures. He observed in his Nobel Prize in Economics speech that "decision makers can satisfice either by finding optimum solutions for a simplified world, or by finding satisfactory solutions for a more realistic world. Neither approach, in general, dominates the other, and both have continued to co-exist in the world of management science".

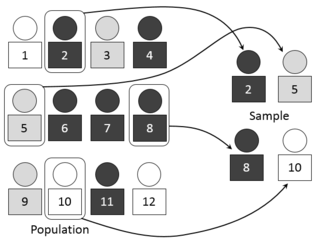

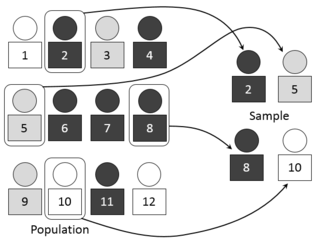

In statistics, quality assurance, and survey methodology, sampling is the selection of a subset, a statistical sample, of individuals from within a statistical population to estimate characteristics of the whole population. Statisticians attempt to collect samples that are representative of the population in question. Sampling has lower costs and faster data collection than measuring the entire population and can provide insights in cases where it is infeasible to measure an entire population.

An interview is a structured conversation where one participant asks questions, and the other provides answers. In common parlance, the word "interview" refers to a one-on-one conversation between an interviewer and an interviewee. The interviewer asks questions to which the interviewee responds, usually providing information. That information may be used or provided to other audiences immediately or later. This feature is common to many types of interviews – a job interview or interview with a witness to an event may have no other audience present at the time, but the answers will be later provided to others in the employment or investigative process. An interview may also transfer information in both directions.

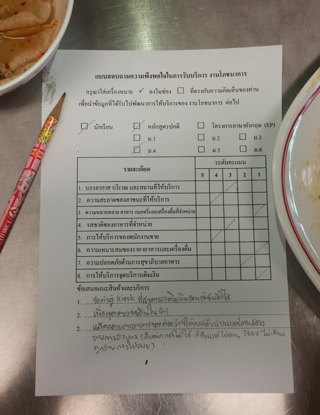

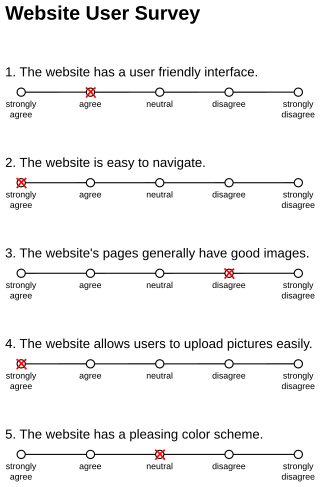

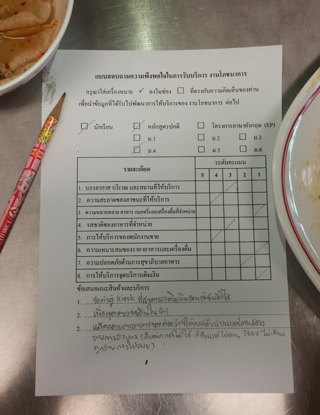

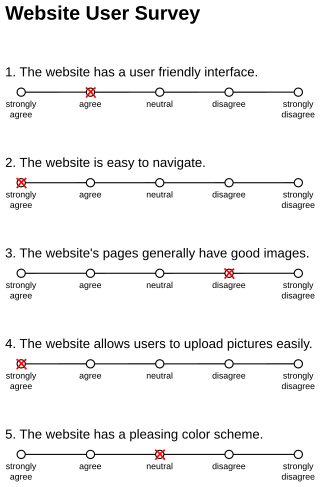

Questionnaire construction refers to the design of a questionnaire to gather statistically useful information about a given topic. When properly constructed and responsibly administered, questionnaires can provide valuable data about any given subject.

Survey methodology is "the study of survey methods". As a field of applied statistics concentrating on human-research surveys, survey methodology studies the sampling of individual units from a population and associated techniques of survey data collection, such as questionnaire construction and methods for improving the number and accuracy of responses to surveys. Survey methodology targets instruments or procedures that ask one or more questions that may or may not be answered.

Quantitative marketing research is the application of quantitative research techniques to the field of marketing research. It has roots in both the positivist view of the world, and the modern marketing viewpoint that marketing is an interactive process in which both the buyer and seller reach a satisfying agreement on the "four Ps" of marketing: Product, Price, Place (location) and Promotion.

An opinion poll, often simply referred to as a survey or a poll, is a human research survey of public opinion from a particular sample. Opinion polls are usually designed to represent the opinions of a population by conducting a series of questions and then extrapolating generalities in ratio or within confidence intervals. A person who conducts polls is referred to as a pollster.

A questionnaire is a research instrument that consists of a set of questions for the purpose of gathering information from respondents through survey or statistical study. A research questionnaire is typically a mix of close-ended questions and open-ended questions. Open-ended, long-term questions offer the respondent the ability to elaborate on their thoughts. The Research questionnaire was developed by the Statistical Society of London in 1838.

Response bias is a general term for a wide range of tendencies for participants to respond inaccurately or falsely to questions. These biases are prevalent in research involving participant self-report, such as structured interviews or surveys. Response biases can have a large impact on the validity of questionnaires or surveys.

Computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) is a telephone surveying technique in which the interviewer follows a script provided by a software application. It is a structured system of microdata collection by telephone that speeds up the collection and editing of microdata and also permits the interviewer to educate the respondents on the importance of timely and accurate data. The software is able to customize the flow of the questionnaire based on the answers provided, as well as information already known about the participant. It is used in B2B services and corporate sales.

Computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) is an interviewing technique in which the respondent or interviewer uses an electronic device to answer the questions. It is similar to computer-assisted telephone interviewing, except that the interview takes place in person instead of over the telephone. This method is usually preferred over a telephone interview when the questionnaire is long and complex. It has been classified as a personal interviewing technique because an interviewer is usually present to serve as a host and to guide the respondent. If no interviewer is present, the term Computer-Assisted Self Interviewing (CASI) may be used. An example of a situation in which CAPI is used as the method of data collection is the British Crime Survey.

In social science research, social-desirability bias is a type of response bias that is the tendency of survey respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others. It can take the form of over-reporting "good behavior" or under-reporting "bad", or undesirable behavior. The tendency poses a serious problem with conducting research with self-reports. This bias interferes with the interpretation of average tendencies as well as individual differences.

In survey research, response rate, also known as completion rate or return rate, is the number of people who answered the survey divided by the number of people in the sample. It is usually expressed in the form of a percentage. The term is also used in direct marketing to refer to the number of people who responded to an offer.

A self-report study is a type of survey, questionnaire, or poll in which respondents read the question and select a response by themselves without any outside interference. A self-report is any method which involves asking a participant about their feelings, attitudes, beliefs and so on. Examples of self-reports are questionnaires and interviews; self-reports are often used as a way of gaining participants' responses in observational studies and experiments.

Automated telephone surveys is a systematic collection a data from demography by making calls automatically to the preset list of respondents at the aim of collecting information and gain feedback via the telephone and the internet. Automated surveys are used for customer research purposes by call centres for customer relationship management and performance management purposes. They are also used for political polling, market research and job satisfaction surveying.

Acquiescence bias, also known as agreement bias, is a category of response bias common to survey research in which respondents have a tendency to select a positive response option or indicate a positive connotation disproportionately more frequently. Respondents do so without considering the content of the question or their 'true' preference. Acquiescence is sometimes referred to as "yea-saying" and is the tendency of a respondent to agree with a statement when in doubt. Questions affected by acquiescence bias take the following format: a stimulus in the form of a statement is presented, followed by 'agree/disagree,' 'yes/no' or 'true/false' response options. For example, a respondent might be presented with the statement "gardening makes me feel happy," and would then be expected to select either 'agree' or 'disagree.' Such question formats are favoured by both survey designers and respondents because they are straightforward to produce and respond to. The bias is particularly prevalent in the case of surveys or questionnaires that employ truisms as the stimuli, such as: "It is better to give than to receive" or "Never a lender nor a borrower be". Acquiescence bias can introduce systematic errors that affect the validity of research by confounding attitudes and behaviours with the general tendency to agree, which can result in misguided inference. Research suggests that the proportion of respondents who carry out this behaviour is between 10% and 20%.

An exit interview is a survey conducted with an individual who is separating from an organization or relationship. Most commonly, this occurs between an employee and an organization, a student and an educational institution, or a member and an association. An organization can use the information gained from an exit interview to assess what should be improved, changed, or remain intact. More so, an organization can use the results from exit interviews to reduce employee, student, or member turnover and increase productivity and engagement, thus reducing the high costs associated with turnover. Some examples of the value of conducting exit interviews include shortening the recruiting and hiring process, reducing absenteeism, improving innovation, sustaining performance, and reducing possible litigation if issues mentioned in the exit interview are addressed.

With the application of probability sampling in the 1930s, surveys became a standard tool for empirical research in social sciences, marketing, and official statistics. The methods involved in survey data collection are any of a number of ways in which data can be collected for a statistical survey. These are methods that are used to collect information from a sample of individuals in a systematic way. First there was the change from traditional paper-and-pencil interviewing (PAPI) to computer-assisted interviewing (CAI). Now, face-to-face surveys (CAPI), telephone surveys (CATI), and mail surveys are increasingly replaced by web surveys.

Computer-assisted survey information collection (CASIC) refers to a variety of survey modes that were enabled by the introduction of computer technology. The first CASIC modes were interviewer-administered, while later on computerized self-administered questionnaires (CSAQ) appeared. It was coined in 1990 as a catch-all term for survey technologies that have expanded over time.

The interviewer effect is the distortion of response to a personal or telephone interview which results from differential reactions to the social style and personality of interviewers or to their presentation of particular questions. The use of fixed-wording questions is one method of reducing interviewer bias. Anthropological research and case-studies are also affected by the problem, which is exacerbated by the self-fulfilling prophecy, when the researcher is also the interviewer it is also any effect on data gathered from interviewing people that is caused by the behavior or characteristics of the interviewer.