Background

Palacios attended Chico State University and transferred to San Francisco State University, at which she earned a BA in Cinema with a concentration in screenwriting. She has been producing theatre works for over three decades. In her specifically Chicana, queer, feminist, and lesbian performances, Palacios emphasizes activism and community organizing. She combines aspects of race, culture, and sexuality in her performances, and she was one of the first openly lesbian/queer stand-up comics in 1982 in San Francisco. She has created several one-woman shows, plays, and screenplays.

Her poems, plays, and anthologies are taught in universities and examined in scholarly settings, usually in the fields of LGBTQ Studies, Chicano Studies, and Feminist Studies. Palacios works with students of a wide range of ages (from elementary students to college students) and has served as a writer, director, and dramaturge for over 400 student theatre works. [3]

Early life

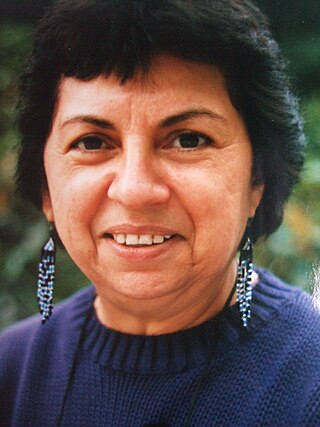

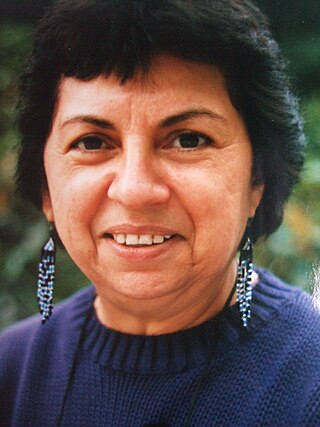

Born and raised in San Jose, California, Chicana lesbian comic Monica Palacios was one of six children and, according to Palacios herself, had a stable childhood. [4] Her older sister also came out as a lesbian later in life, a subject that eventually became a bit of Palacios’ titled “Double Dyke Familia.” [5]

She attended an all girls Catholic school where her love of comedy was already visible. [6] She loved to watch sitcoms and stand up comedians on TV and would try to imitate them for her classmates. She even tried doing stand-up in her high school English classes. [7]

After high school, she attended Chico State University where she began to question her sexuality, however at the time, she had a boyfriend. Although she didn't love him, she thought about marrying because she thought it might just make her life easier. [8] But she eventually broke up with him and came out as bisexual. As she continued to dig into her sexual identity, she knew she needed to “get the hell out of dodge” and at age nineteen Palacios transferred to school in San Francisco, came out as a lesbian, and began performing stand-up. [9]

Stand-up career

The 1980s: Early stand-up career

Palacios “discovered her love for comedy and her sexual identity at the same time.” [10] When she got to school in San Francisco, she hung out in comedy clubs and “took notes.” Then, on her twenty third birthday she went on stage as a dare to herself. [7]

At the beginning of her career, she didn’t want to do lesbian content, she thought it would ruin her dreams of having a mainstream comedy career before it even started. [8] In an interview, Palacios stated that she was “ a novelty back then in 1982 because I was a 23-year-old California native Chicana comic and a lesbian, to boot! Being very in your face about nationality and sexuality, I was called "controversial" and other names that begin with a 'C'.” [8]

Although she first performed at straight comedy clubs, which were known for being harshly racist, sexist, and homophobic, she quickly found herself performing at popular Queer performance venue The Valencia Rose Cabaret. [1]

The Valencia Rose Cabaret

Palacios first went at the Queer establishment, which was founded in 1982 and was the first gay comedy club in the country, [11] just to watch other stand-ups perform. But found herself on stage “almost immediately” and “she was hooked.” [12] She describes the venue as a “big love fest” where she felt fully comfortable to be herself [7] [12]

Palacios had first performed at a straight comedy club to a tepid audience response. But, a few nights later she found herself at The Valencia Rose. She did the same set she had done at the straight club, but she added a bit about her girlfriend and the audience exploded with laughter. [13] The Valencia Rose was a place where comics felt relief from the typical, straight clubs. [11]

After three months of performing at the Valencia Rose Cabaret, she began getting paid to headline there. An experience she describes as “incredible and empowering.” [14]

The 1990s: Transitioning to one woman shows

Though she quickly made a name for herself as a lesbian comic, she found that this “closed as many doors as it opened. [15] Straight clubs wouldn’t let her perform and in 1987 she headed to Los Angeles where she, once again, attempted to become a mainstream performer. [13] But it was a “rerun” of what had happened in San Francisco with straight clubs not being accepting or welcoming to her. [15]

The more time she spent in comedy clubs the more she realized it wasn’t her scene, they had an “aggressive atmosphere.” So she went away and wrote her first solo show, “Latin Lezbo Comic.” In the performance, she sought to put a positive example of a Queer woman on stage. She told hilarious stories about her family and her girlfriends. [12] With this show, her career as a one woman show performer and a playwright was born.

Though she attempted to make her work relatable, she refused to compromise who she was for profit. For example, Palacios noted that “sure I’ll go on Arsenio if I can talk about my girlfriend.” [15] She was known for subverting the white, heteronormative storytelling that is common in stand-up comedy. [16] As her career continued to grow, she also became known for her one woman shows which bridged not only her identities, but also theatrical form as her performances lived in a world somewhere between theater and stand-up.

Themes and influences

The majority of Palacios' writing is about her interpretations of her experiences throughout life as a queer, Chicana woman. [3] She draws inspiration from her family and others close to her. As one of the first comedians in this genre, she often discusses the intersection of queer and Latina identities that develop a liminal identity for people who are marginalized for more than one aspect of their existence. [17]

Her work is known for being unapologetically queer, despite the homophobia that had permeated Latinx communities since long before she began performing. [18] Palacios acknowledges that she often takes uncomfortable topics and makes them more palatable to herself and her audiences with physical comedy, but not without challenges and some pushback. [19] She continues to produce works like The OH! Show, where discussion of sex is intentionally ubiquitous. This is evident in the forward of the play, in which she declares, "...we are sexual beings until we die, or until your partner removes the vibrator from your hands—whichever comes first." [20]

In her performances, Palacios restructures white and heteronormative narratives by using several modes of storytelling. One way by which she does this is adapting popular, and heterosexual, songs to include queer people in the narratives and uproot their heteronormativity. For example, she ends her show Queer Chicano Soul: Thirty Years of Fierce Performance, My Quinceañera Times Two, with a series of song snippets titled the "Vagina Medley." All lyrics were changed to accommodate the addition of the word, such as "I left my vagina in San Francisco," in which "vagina" replaces "heart" in Tony Bennett's I Left My Heart in San Francisco [18] . This performance is made up of a variety of segments of autobiographical narratives, vignettes, segments of standup and mime. This format is reminiscent of traditional carpas that traveled to working-class Latinx people to engage them in theatre and political discourse (like Luis Valdez's El Teatro Campesino). [18] Thus, the backdrop of Los Angeles, a city claimed to be of "Chicanos and Mexicanos" that Palacios has called "complex and brilliant inspiration" for her art, provides a place where she can teach and perform for diverse audiences. [19] Like Queer Chicano Soul, the majority of her shows are grounded in her identity as a Chicana woman, as they switch between English and Spanish and have cultural references throughout.

In 2019, Palacios presented a work titled I’m Still Here as a direct response to the Trump Administration. She pulled from her own past, her upbringing in the 1970s and 80s, in order to escape the “toxic” present and to resist the erasure that seemed to be pressing down on all sides. [14]

Palacios also draws inspiration from Latinx writers Jorge Huerta, Irene Fornes, Migdalia Cruz, Marga Gomez, and several others. [21]

Activism

From 1992–2000, Palacios was the director of VIVA, Lesbian and Gay Latino Artists of Los Angeles. She organized cultural events in Los Angeles County which combined art and activism. The goal of these events was to inspire and promote queer, Latino artists in her community, and the majority of her works are developed to empower them. [22]

Palacios notes that when she was young, activism wasn’t a large part of her performances. But as queer and Latina audience began to thank her for being herself on stage, she realized she wanted to present the most “authentic version” of herself which became how she approached activism. She resisted the temptation to conform. Palacios notes “the more specific I get, the more universal my work.” [14]

Palacios has won awards for her contributions to the queer and Latinx communities. She is a co-founding member of Culture Clash, whose satirical sketches, plays, and screenplays all feature race-based, political, and social commentary. [23]

In 2016, Palacios performed her short play Say Their Names in the international theatre effort "After Orlando" in response to the Orlando nightclub shooting. That same year, she did a presentation about her career titled "Queer Chicana Lesbian Activism Through Theatre & Comedy" at the University of New Mexico. In 2014, she was a panelist at a World AIDs day panel called "Queer Latinidad: Histories of AIDS Consciousness from Los Angeles" at Pitzer College. Palacios does much of her activist work in universities. For example, she performed during Gay and Lesbian awareness month at UC San Diego, UC Santa Barbara, UCLA, and MIT in 1994.

Palacios helped develop and has her own blog on epochalips.com, [24] an online platform where lesbians and allies can discuss similar experiences and find community in these shared moments.

Palacios is also featured in STAND UP STAND OUT, a queer documentary tracing the history of The Valencia Rose Cabaret.

Chicano or Chicana is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans who have a non-Anglo self-image, embracing their Mexican Native ancestry. Chicano was originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture. In the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed in the building of a movement toward political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of indigenous descent. Chicano developed its own meaning separate from Mexican American identity. Youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into the mainstream American culture and embraced their own identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance. The community forged an independent political and cultural movement, sometimes working alongside the Black power movement.

Cherríe Moraga is a Xicana feminist, writer, activist, poet, essayist, and playwright. She is part of the faculty at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the Department of English since 2017, and in 2022 became a distinguished professor. Moraga is also a founding member of the social justice activist group La Red Xicana Indígena, which is network fighting for education, culture rights, and Indigenous Rights. In 2017, she co-founded, with Celia Herrera Rodríguez, Las Maestras Center for Xicana Indigenous Thought, Art, and Social Practice, located on the campus of UC Santa Barbara.

Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa was an American scholar of Chicana feminism, cultural theory, and queer theory. She loosely based her best-known book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), on her life growing up on the Mexico–Texas border and incorporated her lifelong experiences of social and cultural marginalization into her work. She also developed theories about the marginal, in-between, and mixed cultures that develop along borders, including on the concepts of Nepantla, Coyoxaulqui imperative, new tribalism, and spiritual activism. Her other notable publications include This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), co-edited with Cherríe Moraga.

Chicana feminism is a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the United States. Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights for the end of women's oppression in the community.

Marga Gomez is a comedian, writer, performer, and teaching artist from Harlem, New York. She has written and performed in thirteen solo plays which have been presented nationally and internationally. Her acting credits include Off-Broadway and national productions of The Vagina Monologues with Rita Moreno. She also acted in season two of the Netflix series Sense8. At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, Gomez pivoted to adapting and presenting her work for live streaming. She has been featured in online theater festivals from New York to San Diego, as well as a five-week virtual run for Brava, SF where she is an artist-in-residence. She is a GLAAD media award winner and recipient of the 2020 CCI Investing in Artists grant.

Culture Clash is a performance troupe that currently comprises writer-comedians Richard Montoya, Ric Salinas, and Herbert Sigüenza. Their work is of a satirical nature.

Diane Rodriguez was an American theatre artist who directed, wrote and performed. An OBIE Award winning actress, she was known for using comedy to confront various forms of oppression, often with special attention to issues of gender and sexuality.

Luis Alfaro is a Chicano performance artist, writer, theater director, and social activist.

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza is a 1987 semi-autobiographical work by Gloria E. Anzaldúa that examines the Chicano and Latino experience through the lens of issues such as gender, identity, race, and colonialism. Borderlands is considered to be Anzaldúa’s most well-known work and a pioneering piece of Chicana literature.

Laura Aguilar was an American photographer. She was born with auditory dyslexia and attributed her start in photography to her brother, who showed her how to develop in dark rooms. She was mostly self-taught, although she took some photography courses at East Los Angeles College, where her second solo exhibition, Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell, was held. Aguilar used visual art to bring forth marginalized identities, especially within the LA Queer scene and Latinx communities. Before the term Intersectionality was used commonly, Aguilar captured the largely invisible identities of large bodied, queer, working-class, brown people in the form of portraits. Often using her naked body as a subject, she used photography to empower herself and her inner struggles to reclaim her own identity as “Laura”- a lesbian, fat, disabled, and brown person. Although work on Chicana/os is limited, Aguilar has become an essential figure in Chicano art history and is often regarded as an early "pioneer of intersectional feminism” for her outright and uncensored work. Some of her most well-known works are Three Eagles Flying, The Plush Pony Series, and Nature Self Portraits. Aguilar has been noted for her collaboration with cultural scholars such as Yvonne Yarbo-Berjano and receiving inspiration from other artists like Judy Dater. She was well known for her portraits, mostly of herself, and also focused upon people in marginalized communities, including LGBT and Latino subjects, self-love, and social stigma of obesity.

Richard Montoya is an American actor, director, producer, screenwriter, playwright, comedian, and co-founding member of the San Francisco based performance troupe Culture Clash. His work in theatre is largely comedy-based and centers around ideas of racism, immigration, discrimination, and identity in Latin-American communities. He follows in the steps of his father, famous activist José Montoya, and is known for creating social and political change through a variety of artistic expressions.

Diane Francis Christine Felix, also known as Chili D, is an American disc jockey and LGBT activist. She is a third-generation Chicana from Stockton, California.

Juana María Rodríguez is a Cuban-American professor of Ethnic Studies, Gender and Women's Studies, and Performance Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Her scholarly writing in queer theory, critical race theory, and performance studies highlights the intersection of race, gender, sexuality and embodiment in constructing subjectivity.

Henry M. Tavera was an AIDS activist, artistic director, and archivist based in the Mission District of San Francisco, California; his 1979 move to the region put him at the forefront of the AIDS epidemic via his involvement in various HIV/AIDS service organizations as well as AIDS theatre. He also did work around Chicano Gay Activism and teaching/advising. Tavera died on February 27, 2000, at 56 years old from kidney cancer.

Herbert Siguenza is an American actor, writer, visual artist, and performer based in California. He is best known for co-founding the theater performance group Culture Clash, which is still active since its founding in 1984, more than thirty years later. He is currently the playwright-in-residence at the San Diego Rep and has continued to pursue many solo ventures in addition to his group work.

Emma Pérez is an American author and professor, known for her work in queer Chicana feminist studies.

Chicana art emerged as part of the Chicano Movement in the 1960s. It used art to express political and social resistance through different art mediums. Chicana artists explore and interrogate traditional Mexican-American values and embody feminist themes through different mediums such as murals, painting, and photography. The momentum created from the Chicano Movement spurred a Chicano Renaissance among Chicanas and Chicanos. Artists voiced their concerns about oppression and empowerment in all areas of race, gender, class, and sexuality. Chicana feminist artists and Anglo-feminist took a different approach in the way they collaborated and made their work during the 1970s. Chicana feminist artists utilized artistic collaborations and collectives that included men, while Anglo-feminist artists generally utilized women-only participants. Art has been used as a cultural reclamation process for Chicana and Chicano artists allowing them to be proud of their roots by combining art styles to illustrate their multi-cultured lives.

The term Chicanafuturism was originated by scholar Catherine S. Ramírez which she introduced in Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies in 2004. The term is a portmanteau of 'chicana' and 'futurism', inspired by the developing movement of Afrofuturism. The word 'chicana' refers to a woman or girl of Mexican origin or descent. However, 'Chicana' itself serves as a chosen identity for many female Mexican Americans in the United States, to express self-determination and solidarity in a shared cultural, ethnic, and communal identity while openly rejecting assimilation. Ramírez created the concept of Chicanafuturism as a response to white androcentrism that she felt permeated science-fiction and American society. Chicanafuturism can be understood as part of a larger genre of Latino futurisms.

Angélica Becerra is an activist visual artist who primarily works in watercolor and digital media.

The Queer Chicano art scene emerged from Los Angeles during the late 1960s and early 1990s composing of queer Mexican American artists. The scene’s activity included motives and themes relating to political activism, social justice, and identity. The movement was influenced by the respective movements of gay liberation, Chicano civil rights, and women’s liberation. The social and political conditions impacting Chicano communities as well as queer people, including the HIV/AIDS epidemic, are conveyed in the scene’s expressive work.