Coercion involves compelling a party to act in an involuntary manner by the use of threats, including threats to use force against that party. It involves a set of forceful actions which violate the free will of an individual in order to induce a desired response. These actions may include extortion, blackmail, or even torture and sexual assault.

A state is a political entity that regulates society and the population within a territory. Government is considered to form the fundamental apparatus of contemporary states.

A failed state is a state that has lost its ability to fulfill fundamental security and development functions, lacking effective control over its territory and borders. Common characteristics of a failed state include a government incapable of tax collection, law enforcement, security assurance, territorial control, political or civil office staffing, and infrastructure maintenance. When this happens, widespread corruption and criminality, the intervention of state and non-state actors, the appearance of refugees and the involuntary movement of populations, sharp economic decline, and military intervention from both within and without the state are much more likely to occur.

The right of self-defense is the right for people to use reasonable or defensive force, for the purpose of defending one's own life (self-defense) or the lives of others, including, in certain circumstances, the use of deadly force.

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other crimes, and moral support for victims. The primary institutions of the criminal justice system are the police, prosecution and defense lawyers, the courts and the prisons system.

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region, often in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of history, albeit in a variety of different capacities within the political, economic, and social structure of states or ungoverned territories. The term is often applied in the context of China around the end of the Qing Dynasty, especially during the Warlord Era. The term can also be used for any supreme military leader.

In economics and business ethics, a coercive monopoly is a firm that is able to raise prices and make production decisions without the risk that competition will arise to draw away their customers. A coercive monopoly is not merely a sole supplier of a particular kind of good or service, but it is a monopoly where there is no opportunity to compete with it through means such as price competition, technological or product innovation, or marketing; entry into the field is closed. As a coercive monopoly is securely shielded from the possibility of competition, it is able to make pricing and production decisions with the assurance that no competition will arise. It is a case of a non-contestable market. A coercive monopoly has very few incentives to keep prices low and may deliberately price gouge consumers by curtailing production.

In political science, legitimacy is the right and acceptance of an authority, usually a governing law or a regime. Whereas authority denotes a specific position in an established government, the term legitimacy denotes a system of government—wherein government denotes "sphere of influence". An authority viewed as legitimate often has the right and justification to exercise power. Political legitimacy is considered a basic condition for governing, without which a government will suffer legislative deadlock(s) and collapse. In political systems where this is not the case, unpopular regimes survive because they are considered legitimate by a small, influential elite. In Chinese political philosophy, since the historical period of the Zhou dynasty, the political legitimacy of a ruler and government was derived from the Mandate of Heaven, and unjust rulers who lost said mandate therefore lost the right to rule the people.

"Politics as a Vocation" is an essay by German economist and sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920). It originated in the second lecture of a series he gave in Munich to the "Free Students Union" of Bavaria on 28 January 1919. This happened during the German Revolution when Munich itself was briefly the capital of the Bavarian Socialist Republic. Weber gave the speech based on handwritten notes which were transcribed by a stenographer. The essay was published in an extended version in July 1919, and translated into English only after World War II. The essay is today regarded as a classic work of political science and sociology.

Self-ownership is the concept of property in one's own body, often expressed as the moral or natural right of a person to have bodily integrity meaning the exclusive right to control one's own body including one's life, where 'control' means exerting any physical interference and 'exclusive' means having the right to install and enforce a ban on other people doing this. Since the legal norm of property title claim incapacitates other people from claiming property title over the same resource at the same time, the right to control or interfere with one's own body in any arbitrary way is secured. Anarcho-capitalism defines self-ownership as the exclusive right to control one's body as long as the owner does not aggress upon others, leading to the concept of the sovereign individual. In Minarchism the 'exclusive right' is understood by separating the 'liberty-to' from the 'liberty-from' where for each person the 'liberty-to' is restricted by all the 'liberty's-from' of others, effectively subjecting the 'liberty-to' to the ban on the usage of force. Thereafter self-ownership means the exclusive right to control one's body insofar considering action between inhabitants and not involving the state, making it roughly a pacifist morality only among inhabitants. Self-ownership is a central idea in several political philosophies that emphasize individualism, such as libertarianism and liberalism.

Rational-legal authority is a form of leadership in which the authority of an organization or a ruling regime is largely tied to legal rationality, legal legitimacy and bureaucracy. The majority of the modern states of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are rational-legal authorities, according to those who use this form of classification.

The three-component theory of stratification, more widely known as Weberian stratification or the three class system, was developed by German sociologist Max Weber with class, status and party as distinct ideal types. Weber developed a multidimensional approach to social stratification that reflects the interplay among wealth, prestige and power.

The non-aggression principle (NAP), also called the non-aggression axiom, is the fundamental principle of morality that states that any person is permitted do everything with his property except aggression, defined as the initiation of forceful action, which is in turn defined as 'the application or threat of' 'physical interference or fraud ', any of which without consent. The principle is also called the non-initiation of force. The principle incorporates universal enforcability.

State-building as a specific term in social sciences and humanities, refers to political and historical processes of creation, institutional consolidation, stabilization and sustainable development of states, from the earliest emergence of statehood up to the modern times. Within historical and political sciences, there are several theoretical approaches to complex questions related to the role of various contributing factors in state-building processes.

Legitimation crisis refers to a decline in the confidence of administrative functions, institutions, or leadership. The term was first introduced in 1973 by Jürgen Habermas, a German sociologist and philosopher. Habermas expanded upon the concept, claiming that with a legitimation crisis, an institution or organization does not have the administrative capabilities to maintain or establish structures effective in achieving their end goals. The term itself has been generalized by other scholars to refer not only to the political realm, but to organizational and institutional structures as well. While there is not unanimity among social scientists when claiming that a legitimation crisis exists, a predominant way of measuring a legitimation crisis is to consider public attitudes toward the organization in question.

In sociology, authority is the legitimate or socially approved power which one person or a group possesses and practices over another. The element of legitimacy is vital to the notion of authority and is the main means by which authority is distinguished from the more general concept of power.

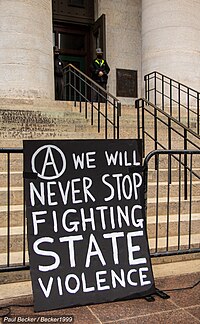

Anti-statism is any approach to social, economic or political philosophy that rejects statism. An anti-statist is one who opposes intervention by the state into personal, social and economic affairs. In anarchism, this is characterized by a complete rejection of all involuntary hierarchical rulership.

In law, "legitimacy" is distinguished from "legality". An action can be legal but not legitimate or vice versa it can be legitimate but not legal.

Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1990 is a 1990 book by the American political scientist Charles Tilly.

State capacity is the ability of a government to accomplish policy goals, either generally or in reference to specific aims. More narrowly, state capacity often refers to the ability of a state collect taxes, enforce law and order, and provide public goods.