A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect the dead, from interment, to various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in their honor. Customs vary between cultures and religious groups. Funerals have both normative and legal components. Common secular motivations for funerals include mourning the deceased, celebrating their life, and offering support and sympathy to the bereaved; additionally, funerals may have religious aspects that are intended to help the soul of the deceased reach the afterlife, resurrection or reincarnation.

A mastaba, also mastabah, mastabat or pr-djt, is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks. These edifices marked the burial sites of many eminent Egyptians during Egypt's Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom. In the Old Kingdom epoch, local kings began to be buried in pyramids instead of in mastabas, although non-royal use of mastabas continued for over a thousand years. Egyptologists call these tombs mastaba, from the Arabic word مصطبة (maṣṭaba) "stone bench".

Neolithic architecture refers to structures encompassing housing and shelter from approximately 10,000 to 2,000 BC, the Neolithic period. In southwest Asia, Neolithic cultures appear soon after 10,000 BC, initially in the Levant and from there into the east and west. Early Neolithic structures and buildings can be found in southeast Anatolia, Syria, and Iraq by 8,000 BC with agriculture societies first appearing in southeast Europe by 6,500 BC, and central Europe by ca. 5,500 BC (of which the earliest cultural complexes include the Starčevo-Koros, Linearbandkeramic, and Vinča.

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objects in it, and covering it over. A funeral is a ceremony that accompanies the final disposition. Evidence suggests that some archaic and early modern humans buried their dead. Burial is often seen as indicating respect for the dead. It has been used to prevent the odor of decay, to give family members closure and prevent them from witnessing the decomposition of their loved ones, and in many cultures it has been seen as a necessary step for the deceased to enter the afterlife or to give back to the cycle of life.

A kurgan is a type of tumulus constructed over a grave, often characterized by containing a single human body along with grave vessels, weapons and horses. Originally in use on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, kurgans spread into much of Central Asia and Eastern, Southeast, Western and Northern Europe during the 3rd millennium BC.

Shanidar Cave is an archaeological site located on Bradost Mountain, within the Zagros Mountains, in the Erbil Governorate of Kurdistan Region in northern Iraq. It is known for the discovery of Neanderthal remains at the site, most notably Shanidar 1, who survived several injuries during his life, possibly due to care from others in his group, and Shanidar 4, the famed 'flower burial'. Until this discovery, Cro-Magnons, the earliest known H. sapiens in Europe, were the only individuals known for purposeful, ritualistic burials.

A morgue or mortuary is a place used for the storage of human corpses awaiting identification (ID), removal for autopsy, respectful burial, cremation or other methods of disposal. In modern times, corpses have customarily been refrigerated to delay decomposition.

In archaeology and anthropology, the term excarnation refers to the practice of removing the flesh and organs of the dead before burial. Excarnation may be achieved through natural means, such as leaving a dead body exposed to the elements or for animals to scavenge; or by butchering the corpse by hand. Following excarnation, some societies retrieved the bones for burial. Excarnation has been practiced throughout the world for hundreds of thousands of years. The earliest archaeological evidence of excarnation is from the Awash River Valley in Ethiopia, 160,000 years ago. Examples of excarnation include "sky burials" in parts of Asia, the Zoroastrian "Tower of Silence", and Native American "tree burials". Excarnation is practiced for a variety of spiritual and practical reasons, including the Tibetian spiritual belief that excarnation is the most generous form of burial and the Comanche practical concern that in the winter the ground is too hard for an underground burial. Excarnation sites are identifiable in the archaeological record by a concentration of smaller bones, which would be the bones that would be the easiest to fall off the body, and that would not be noticed by practitioners of excarnation.

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are items buried along with a body.

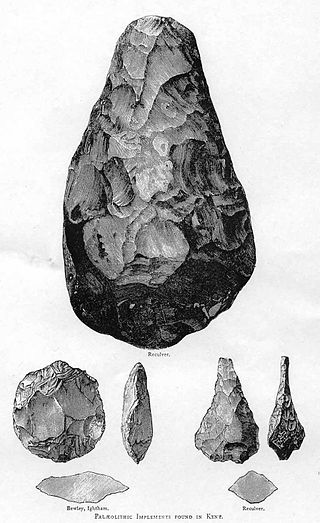

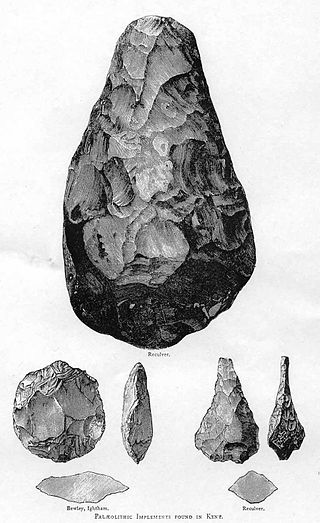

The Middle Paleolithic is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleolithic in African archeology. The Middle Paleolithic broadly spanned from 300,000 to 30,000 years ago. There are considerable dating differences between regions. The Middle Paleolithic was succeeded by the Upper Paleolithic subdivision which first began between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago. Pettit and White date the Early Middle Paleolithic in Great Britain to about 325,000 to 180,000 years ago, and the Late Middle Paleolithic as about 60,000 to 35,000 years ago. The Middle Paleolithic was in the geological Chibanian and Late Pleistocene ages.

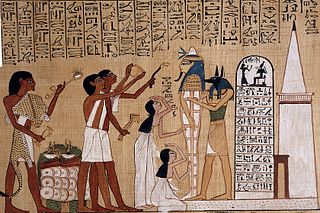

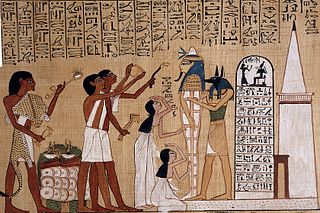

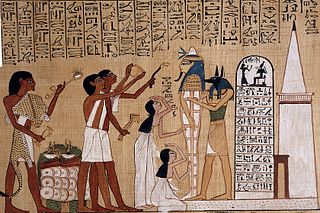

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

The Xagħra Stone Circle, also known as the Xagħra Hypogeum or the Brochtorff Circle, is a Neolithic funerary complex located in Xagħra, Gozo, Malta. It consists of a series of caves which were used to bury the dead, and which were surrounded by a walled enclosure. It mainly dates back to around 3000 to 2400 BC, although the earliest tombs at the site date back to 4100 to 3800 BC. The caves collapsed sometime before 2000 BC, and the site was later used for domestic and agricultural purposes.

Town Creek Indian Mound is a prehistoric Native American archaeological site located near present-day Mount Gilead, Montgomery County, North Carolina, in the United States. The site, whose main features are a platform mound with a surrounding village and wooden defensive palisade, was built by the Pee Dee, a South Appalachian Mississippian culture people that developed in the region as early as 980 CE. They thrived in the Pee Dee River region of North and South Carolina during the Pre-Columbian era. The Town Creek site was an important ceremonial site occupied from about 1150—1400 CE. It was abandoned for unknown reasons. It is the only ceremonial mound and village center of the Pee Dee located within North Carolina.

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs, tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of ancestor veneration or as a publicly directed dynastic display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the lives of the living.

Charon's obol is an allusive term for the coin placed in or on the mouth of a dead person before burial. Greek and Latin literary sources specify the coin as an obol, and explain it as a payment or bribe for Charon, the ferryman who conveyed souls across the river that divided the world of the living from the world of the dead. Archaeological examples of these coins, of various denominations in practice, have been called "the most famous grave goods from antiquity."

The secondary burial, or “double funeral” is a feature of prehistoric and historic gravesites. The term refers to remains that represent an exhumation and reburial, whether intentional or accidental.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to prehistoric technology.

Digging, also referred to as excavation, is the process of using some implement such as claws, hands, manual tools or heavy equipment, to remove material from a solid surface, usually soil, sand or rock on the surface of Earth. Digging is actually the combination of two processes, the first being the breaking or cutting of the surface, and the second being the removal and relocation of the material found there. In a simple digging situation, this may be accomplished in a single motion, with the digging implement being used to break the surface and immediately fling the material away from the hole or other structure being dug.

Prehistoric religion is the religious practice of prehistoric cultures. Prehistory, the period before written records, makes up the bulk of human experience; over 99% of human experience occurred during the Paleolithic period alone. Prehistoric cultures spanned the globe and existed for over two and a half million years; their religious practices were many and varied, and the study of them is difficult due to the lack of written records describing the details of their faiths.