Related Research Articles

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600, varying regionally. It was known for building large, earthen platform mounds, and often other shaped mounds as well. It was composed of a series of urban settlements and satellite villages linked together by loose trading networks. The largest city was Cahokia, believed to be a major religious center located in what is present-day southern Illinois.

The Natchez are a Native American people who originally lived in the Natchez Bluffs area in the Lower Mississippi Valley, near the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi, in the United States. They spoke a language with no known close relatives, although it may be very distantly related to the Muskogean languages of the Creek Confederacy. An early American geographer noted in his 1797 gazetteer that they were also known as the "Sun Set Indians".

The Taposa were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands from what is now Mississippi in the United States.

The Avoyel or Avoyelles were a small Native American tribe who at the time of European contact inhabited land near the mouth of the Red River at its confluence with the Atchafalaya River near present-day Marksville, Louisiana. The Avoyel are a member of the federally recognized Native American tribe and sovereign nation of the Tunica Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana.

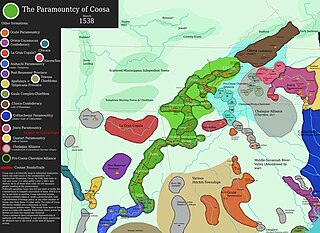

The Coosa chiefdom was a powerful Native American paramount chiefdom in what are now Gordon and Murray counties in Georgia, in the United States. It was inhabited from about 1400 until about 1600, and dominated several smaller chiefdoms. The total population of Coosa's area of influence, reaching into present-day Tennessee and Alabama, has been estimated at 50,000.

The Taensa were a Native American people whose settlements at the time of European contact in the late 17th century were located in present-day Tensas Parish, Louisiana. The meaning of the name, which has the further spelling variants of Taenso, Tinsas, Tenza or Tinza, Tahensa or Takensa, and Tenisaw, is unknown. It is believed to be an autonym. The Taensa should not be confused with the Avoyel, known by the French as the petits Taensas, who were mentioned in writings by explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville in 1699. The Taensa are more closely related to the Natchez people and both are considered descendants of the late prehistoric Plaquemine culture.

Étienne Perier or Étienne de Perier (1686–1766), also known as Perier the Elder, was a French naval officer and governor of French Louisiana from 1726 to 1733. His time as governor included some notable achievements, including the construction of the first levee along the Mississippi River in 1727. In response to the Natchez Revolt, he attempted to completely destroy the Natchez people, which increased Native American hostility toward the French in the territory. Because he failed to secure the safety of the colony, Perier was recalled as governor in March 1733. He later distinguished himself as a naval officer and privateer, including during the capture of HMS Northumberland in 1744.

The Biloxi tribe are Native Americans of the Siouan language family. They call themselves by the autonym Tanêks(a) in Siouan Biloxi language. When first encountered by Europeans in 1699, the Biloxi inhabited an area near the coast of the Gulf of Mexico near what is now the city of Biloxi, Mississippi. They were eventually forced west into Louisiana and eastern Texas. The Biloxi language--Tanêksąyaa ade--has been extinct since the 1930s, when the last known semi-speaker, Emma Jackson, died.

The Quinipissa were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands who were living on the lower Mississippi River, in present-day Louisiana, as reported by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle in 1682.

The Acolapissa were a small tribe of Native Americans of North America, who lived in the Southeast of what is the present-day United States. They lived along the banks of the Pearl River, between present-day Louisiana and Mississippi. They are believed to have spoken a Muskogean language, closely related to the Choctaw and Chickasaw spoken by other Southeast tribes of the Muskogean family.

Bayou Manchac is an 18-mile-long (29 km) bayou in southeast Louisiana, USA. First called the Iberville River by its French discoverers, the bayou was once a very important waterway linking the Mississippi River to the Amite River. East Baton Rouge Parish lies on its northern side, while its southern side is divided between Ascension Parish and Iberville Parish. The large unincorporated community of Prairieville and the city of St. Gabriel both lie on its southern side.

The Tangipahoa were a Native American tribe that lived just north of Lake Pontchartrain and between the Pearl River and the Mississippi River.

The Yatasi were Native American peoples from northwestern Louisiana that were part of the Natchitoches Confederacy of the Caddo Nation. Today they are enrolled in the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma.

The Opelousa were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands in Louisiana. They lived near present-day Opelousas, Louisiana, west of the lower Mississippi River, in the 18th century. At various times, they allied with the neighboring Atakapa and Chitimacha peoples.

The siege of Pensacola included two separate attempts in 1707 by English-supported Creek Indians to capture the town and fortress of Pensacola, one of two major settlements in Spanish Florida.

The Bayogoula were a Native American tribe from Louisiana in the southern United States.

The Taensa language was spoken by the Taensa people originally of northeastern Louisiana, and later with historical importance in Alabama. Though poorly documented, it was probably a dialect of the Natchez language. It was also the subject of controversy beginning in 1880–1882, when a French student published a grammar and sample texts of a language that he claimed to be Taensa, though it bore no resemblance to Natchez — these publications are generally considered to be a hoax and the language it described to be invented.

The Tomahittan were Native Americans whom Virginians James Needham and Gabriel Arthur tried to contact to bypass the taxes of the Occaneechi "middlemen" natives.

Robbie Franklyn Ethridge is an American anthropologist and author. She is a professor of anthropology at the University of Mississippi.

The Mississippian shatter zone describes the period from 1540 to 1730 in the southeastern part of the present United States. During that time, the interaction between European explorers and colonists transformed the Native American cultures of that region. In 1540 dozens of chiefdoms and several paramount chiefdoms were scattered throughout the southeast. Chiefdoms featured a noble class ruling a large number of commoners and were characterized by villages and towns with large earthen mounds and complex religious practices. Some chiefdoms, known as paramount chieftains, ruled or influenced large areas. The chiefdoms were ravaged by the de Soto and other Spanish exploratory missions in the 1540s through the 1560s and their decline began.

References

- John Reed Swanton (1952). The Indian Tribes of North America. Genealogical Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4.