The Himalayan tahr is a large even-toed ungulate native to the Himalayas in southern Tibet, northern India, western Bhutan and Nepal. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, as the population is declining due to hunting and habitat loss.

The chamois or Alpine chamois is a species of goat-antelope native to the mountains in Southern Europe, from the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the Dinarides, the Tatra to the Carpathian Mountains, the Balkan Mountains, the Rila–Rhodope massif, Pindus, the northeastern mountains of Turkey, and the Caucasus. It has also been introduced to the South Island of New Zealand. Some subspecies of chamois are strictly protected in the EU under the European Habitats Directive.

The Alpine ibex, which is also known as the steinbock, is a species of goat that lives in the Alps of Europe. It is one of ten species in the genus Capra and its closest living relative is the Iberian ibex. The Alpine ibex is a sexually dimorphic species; males are larger and carry longer horns than females. Its coat is brownish-grey. Alpine ibexes tend to live in steep, rough terrain and open alpine meadows. They can be found at elevations as high as 3,300 m (10,800 ft) and their sharp hooves allow them to scale their mountainous habitat.

The markhor is a large wild Capra (goat) species native to South Asia and Central Asia, mainly within Pakistan, India, the Karakoram range, parts of Afghanistan, and the Himalayas with Pakistan having the highest population of 5500. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened since 2015.

The takin, also called cattle chamois or gnu goat, is a large species of ungulate of the subfamily Caprinae found in the eastern Himalayas. It includes four subspecies: the Mishmi takin, the golden takin, the Tibetan takin, and the Bhutan takin.

The mountain gazelle, also called the true gazelle, the Israeli gazelle, or the Palestine mountain gazelle, is a species of gazelle that is widely but unevenly distributed.

A cloven hoof, cleft hoof, divided hoof, or split hoof is a hoof split into two toes. Members of the mammalian order Artiodactyla that possess this type of hoof include cattle, deer, pigs, antelopes, gazelles, goats, and sheep.

The gorals are four species in the genus Naemorhedus. They are small ungulates with a goat-like or antelope-like appearance. Until recently, this genus also contained the serow species.

The long-tailed goral or Amur goral is a species of ungulate of the family Bovidae found in the mountains of eastern and northern Asia, including Russia, China, and Korea. A population of this species exists in the Korean Demilitarized Zone, near the tracks of the Donghae Bukbu Line. The species is classified as endangered in South Korea, with an estimated population less than 250. It has been designated South Korean natural monument 217. In 2003, the species was reported as being present in Arunachal Pradesh, in northeast India.

The walia ibex is a vulnerable species of ibex. It is sometimes considered an endemic subspecies of the Alpine ibex. If the population were to increase, the surrounding mountain habitat would be sufficient to sustain only 2,000 ibex. The adult walia ibex's only known wild predator is the hyena. However, young ibex are often hunted by a variety of fox and cat species. The ibex are members of the goat family, and the walia ibex is the southernmost of today's ibexes. In the late 1990s, the walia ibex went from endangered to critically endangered due to the declining population. The walia ibex is also known as the Abyssinian ibex. Given the small distribution range of the Walia ibex in its restricted mountain ecosystem, the presence of a large number of domestic goats may pose a serious threat that can directly affect the survival of the population.

The Siberian ibex, also known using regionalized names including Altai ibex,Asian ibex, Central Asian ibex, Gobi ibex, Himalayan ibex, Mongolian ibex or Tian Shan ibex, is a polytypic species of ibex, a wild relative of goats and sheep. It lives in Central Asia, and is, by far, the most widely-distributed species in the genus Capra. In terms of population stability, Siberian ibex are currently ranked as Near Threatened, mostly due to over-hunting, low densities and overall decline; still, reliable data is minimal and difficult to come by, in addition to the animals’ expansive natural range, so accurate observations are still scant. The Siberian ibex has, formerly, been treated as a subspecies of the Eurasian Alpine ibex, and whether or not it is a single species or a complex of distinct units that stand out as genetically-distinct is still not entirely clear. The Siberian ibex is the longest and heaviest member of the genus Capra, though its shoulder height is slightly surpassed by the markhor.

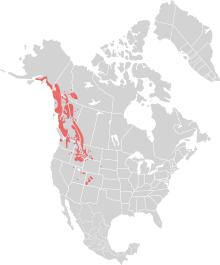

The mountain cottontail or Nuttall's cottontail is a species of mammal in the family Leporidae. It is found in Canada and the United States.

Odocoileus lucasi, known commonly as the American mountain deer, is an extinct species of North American deer.

The Sichuan takin or Tibetan takin is a subspecies of takin (goat-antelope). Listed as a vulnerable species, the Sichuan takin is native to Tibet and the provinces of Sichuan, Gansu and Xinjiang in the People's Republic of China.

The goat or domestic goat is a species of domesticated goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the family Bovidae, meaning it is closely related to the sheep. There are over 300 distinct breeds of goat. It is one of the oldest domesticated species of animal, according to archaeological evidence that its earliest domestication occurred in Iran at 10,000 calibrated calendar years ago.

The Chinese goral, also known as the grey long-tailed goral or central Chinese goral, is a species of goral, a small goat-like ungulate, native to mountainous regions of Myanmar, China, India, Thailand, Vietnam, and possibly Laos. In some parts of its range, it is overhunted. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed it as a "vulnerable species".

There are at least 14 large mammal and 50 small mammal species known to occur in Glacier National Park.

The Alberta Mountain forests are a temperate coniferous forests ecoregion of Western Canada, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) categorization system.

The North Central Rockies forests is a temperate coniferous forest ecoregion of Canada and the United States. This region overlaps in large part with the North American inland temperate rainforest and gets more rain on average than the South Central Rockies forests and is notable for containing the only inland populations of many species from the Pacific coast.

There are at least 9 large terrestrial mammals, 50 small mammals, and 14 marine mammal species known to occur in Olympic National Park.