Related Research Articles

Edward Bellamy was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel Looking Backward. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerous "Nationalist Clubs" dedicated to the propagation of his political ideas.

Feminist science fiction is a subgenre of science fiction focused on such feminist themes as: gender inequality, sexuality, race, economics, reproduction, and environment. Feminist SF is political because of its tendency to critique the dominant culture. Some of the most notable feminist science fiction works have illustrated these themes using utopias to explore a society in which gender differences or gender power imbalances do not exist, or dystopias to explore worlds in which gender inequalities are intensified, thus asserting a need for feminist work to continue.

Science fiction and fantasy serve as important vehicles for feminist thought, particularly as bridges between theory and practice. No other genres so actively invite representations of the ultimate goals of feminism: worlds free of sexism, worlds in which women's contributions are recognized and valued, worlds that explore the diversity of women's desire and sexuality, and worlds that move beyond gender.

A utopia typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, which describes a fictional island society in the New World. It can also refer to an intentional community.

The Dispossessed is a 1974 anarchist utopian science fiction novel by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin, one of her seven Hainish Cycle novels. It is one of a small number of books to win all three Hugo, Locus and Nebula Awards for Best Novel. It achieved a degree of literary recognition unusual for science fiction due to its exploration of themes such as anarchism and revolutionary societies, capitalism, utopia, individualism, and collectivism.

Utopian and dystopian fiction are subgenres of science fiction that explore social and political structures. Utopian fiction portrays a setting that agrees with the author's ethos, having various attributes of another reality intended to appeal to readers. Dystopian fiction offers the opposite: the portrayal of a setting that completely disagrees with the author's ethos. Some novels combine both genres, often as a metaphor for the different directions humanity can take depending on its choices, ending up with one of two possible futures. Both utopias and dystopias are commonly found in science fiction and other types of speculative fiction.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, also known by her first married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, writer, lecturer, advocate for social reform, and eugenicist. She was a utopian feminist and served as a role model for future generations of feminists because of her unorthodox concepts and lifestyle. She has been inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. Her best remembered work today is her semi-autobiographical short story "The Yellow Wallpaper", which she wrote after a severe bout of postpartum psychosis.

The Emerald City of Oz is the sixth of L. Frank Baum's fourteen Land of Oz books. It was also adapted into a Canadian animated film in 1987. Originally published on July 20, 1910, it is the story of Dorothy Gale and her Uncle Henry and Aunt Em coming to live in Oz permanently. While they are toured through the Quadling Country, the Nome King is assembling allies for an invasion of Oz. This is the first time in the Oz series that Baum made use of double plots for one of the books.

Looking Backward: 2000–1887 is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

Herland is a utopian novel from 1915, written by American feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The book describes an isolated society composed entirely of women, who bear children without men. The result is an ideal social order: free of war, conflict, and domination. It was first published in monthly installments as a serial in 1915 in The Forerunner, a magazine edited and written by Gilman between 1909 and 1916, with its sequel, With Her in Ourland beginning immediately thereafter in the January 1916 issue. The book is often considered to be the middle volume in her utopian trilogy, preceded by Moving the Mountain (1911). It was not published in book form until 1979.

Mizora is a feminist science fiction utopian novel by Mary E. Bradley Lane, first published in 1880–81, when it was serialized in the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper. It appeared in book form in 1890. Mizora is "the first portrait of an all-female, self-sufficient society," and "the first feminist technological Utopia."

Women and Economics – A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution is a book written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman and published in 1898. It is considered by many to be her single greatest work, and as with much of Gilman's writing, the book touched a few dominant themes: the transformation of marriage, the family, and the home, with her central argument: “the economic independence and specialization of women as essential to the improvement of marriage, motherhood, domestic industry, and racial improvement.”

The Forerunner was a monthly magazine produced by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, from 1909 through 1916. During that time, she wrote all of every issue — editorials, critical articles, book reviews, essays, poems, stories, and six serialized novels. Gilman's drive for social change was the inspiration for Forerunner and its controversial articles. She succeeded in administering progressive ideas for change to the magazine's readers, growing support for her desires during the women's suffrage movement. The magazine was based in New York City.

Woman on the Edge of Time is a 1976 novel by American writer Marge Piercy. It is considered a classic of utopian speculative science fiction as well as a feminist classic. The novel was originally published by Alfred A. Knopf. Piercy draws on several inspirations to write this novel such as utopian studies, technoscience, socialization, and female fantasies. One of Piercy's main inspirations for her utopian novels is Plato's Republic. Piercy describes the novel as, "if only…" Piercy even compares Woman on the Edge of Time and another one of her utopian novels He, She, and It when discussing the themes and inspirations behind it.

Three Hundred Years Hence is a utopian science fiction novel by author Mary Griffith, published in 1836. It is the first known utopian novel written by an American woman. The novel was originally published in 1836 as part of Griffith's collection, Camperdown, or News from Our Neighborhood, and later published by Prime Press in 1950 in an edition of 300 copies.

New Amazonia: A Foretaste of the Future is a feminist utopian novel, written by Elizabeth Burgoyne Corbett and first published in 1889. It was one element in the wave of utopian and dystopian literature that marked the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Unveiling a Parallel: A Romance is a feminist science fiction and utopian novel published in 1893. The first edition of the book attributed authorship to "Two Women of the West". They were Alice Ilgenfritz Jones and Ella Robinson Merchant, writers who lived in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Marie Stevens Case Howland was an American feminist writer of the nineteenth century, who was closely associated with the utopian socialist movements of her era.

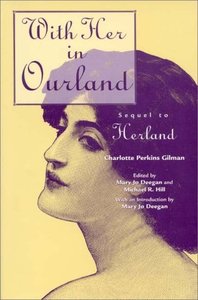

With Her in Ourland: Sequel to Herland is a feminist novel and sociological commentary written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The novel is a follow-up and sequel to Herland (1915), and picks up immediately following the events of Herland, with Terry, Van, and Ellador traveling from Herland to "Ourland". The majority of the novel follows Van and Ellador's travels throughout the world, and particularly the United States, with Van curating their explorations through the then-modern world, while Ellador offers her commentary and "prescriptions" from a Herlander's perspective, discussing topics such as the First World War, foot binding, education, politics, economics, race relations, and gender relations.

Beatrice the Sixteenth: Being the Personal Narrative of Mary Hatherley, M.B., Explorer and Geographer is a 1909 feminist utopian novel by the English lawyer, writer and activist Irene Clyde—who is remembered as non-binary, transgender, or as a trans woman—about a time traveller who discovers a lost world, which contains a postgender society.

References

- ↑ Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Moving the Mountain, New York, Charlton Co., 1911.

- ↑ Kenneth M. Roemer, The Obsolete Necessity: America in Utopian Writings, 1888–1900, Kent, OH, Kent State University Press, 1976.

- ↑ Jean Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel in America, 1886–1896: The Politics of Form, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1984.

- ↑ Matthew Beaumont, Utopia Ltd.: Ideologies of Social Dreaming in England, 1870–1900, Leiden, Brill Academic Publishers, 2005.

- ↑ Polly Wynn Allen, Building Domestic Liberty: Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Architectural Feminism, Amherst, MA, University of Massachusetts Press, 1988; p. 89.

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, p. 37. (Page citations refer to the 1911 book edition.)

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, p. 48.

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, pp. 60, 172.

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, p. 41.

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, p. 288.

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, p. 108.

- ↑ Ruth Roach Pierson, Women and Peace: Theoretical, Historical, and Practical Perspectives, New York, Routledge, 1987; p. 160.

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, p. 259.

- ↑ Moving the Mountain, pp. 106-7.