On 11 November 2000, a fire in the tunnel of Gletscherbahn Kaprun 2 funicular in Kaprun, Austria, killed 155 people. The cause was traced to a faulty fan heater. Most of the victims were skiers on their way to the Kitzsteinhorn Glacier. To date, this incident remains the deadliest rail disaster in Austrian history.

A conductor or guard is a train crew member responsible for operational and safety duties that do not involve actual operation of the train/locomotive. The conductor title is most common in North American railway operations, but the role is common worldwide under various job titles. In Commonwealth English, a conductor is also known as guard or train manager.

A caboose is a crewed North American railroad car coupled at the end of a freight train. Cabooses provide shelter for crew at the end of a train, who were formerly required in switching and shunting, keeping a lookout for load shifting, damage to equipment and cargo, and overheating axles.

The Monson Railroad was a 2 ft narrow gauge railway, which operated between Monson Junction on the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad and Monson, Maine. The primary purpose of this railroad was to serve several slate mines and finishing houses in Monson. According to the Scientific American of 17 May 1890, it was the smallest railroad in the United States.

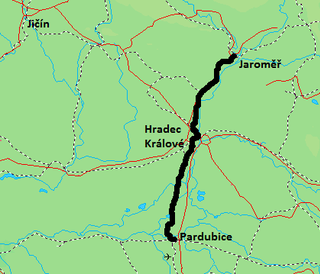

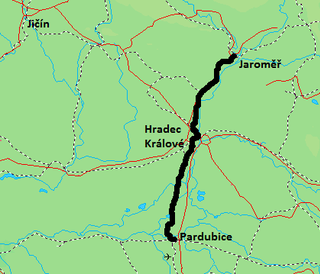

The Stéblová train disaster was a railway accident that occurred on 14 November 1960 at 17:42 CET on a single-track railway in Stéblová in Eastern Bohemia, Czechoslovakia. At 17:42 CET, a passenger steam train 608 traveling at a speed of 55 km/h collided with a diesel railcar 653 traveling at a speed of 60 km/h. 118 people died as a result of the accident and 110 were badly injured. It remains the deadliest accident in the history of Czech railway transport.

A brakeman is a rail transport worker whose original job was to assist the braking of a train by applying brakes on individual wagons. The advent of through brakes, brakes on every wagon which could be controlled by the driver, made this role redundant, although the name lives on, for example, in the United States where brakemen carry out a variety of functions both on the track and within trains.

The Great Train Wreck of 1856 occurred in Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania, between Camp Hill station and Fort Washington station, on July 17, 1856. Two trains, traveling on the same track in converging directions, collided, killing between 59 and 67, and injuring over 100. The incident was referred to as The Camp Hill Disaster in Montgomery County, and The Picnic Train Tragedy in Philadelphia. It was the deadliest railroad catastrophe in the world up to that time and became one of the signature events of its era.

The San Bernardino train disaster, was a combination of two separate but related incidents that occurred in San Bernardino, California, United States: a runaway train derailment on May 12, 1989; and the subsequent failure on May 25, 1989, of the Calnev Pipeline, a petroleum pipeline adjacent to the tracks which was damaged by earth-moving equipment during the crash cleanup.

In a railway accident, telescoping occurs when the underframe of one vehicle overrides that of another, and smashes through the second vehicle's body. The term is derived from the resulting appearance of the two vehicle bodies: the body of one vehicle may appear to be slid inside the other like the tubes of a collapsible telescope – the body sides, roof and underframe of the latter vehicle being forced apart from each other.

The Murulla rail accident involved the collision of the Sydney-bound Northern Mail with runaway goods wagons near Murrurundi, in the Upper Hunter Valley on 13 September 1926; 26 persons died. A goods train had become divided and the attempts of the train crew to reunite the portions resulted in 12 vehicles running away down a steep gradient, and colliding with the approaching mail train. This was the worst accident on the New South Wales rail network until the Granville railway disaster in 1977.

The Rockport train wreck occurred in Rockport in Mansfield Township, New Jersey, United States, about three miles outside of Hackettstown, on June 16, 1925. A violent storm washed debris onto a grade crossing, derailing a Lackawanna Railroad (DL&W) train. The crash killed 42 passengers and five crewmen and injured twenty-three others.

The Michigan train wreck was the worst rail disaster in both North Dakota and Great Northern Railway history. It happened on August 9, 1945, at Michigan, North Dakota, and involved Great Northern's premier train, the Empire Builder.

The Shepherdsville train wreck was a fatal rail accident that killed at least 49 people when an express collided with a local train at Shepherdsville, Kentucky on December 20, 1917. It was the deadliest train wreck in Kentucky's history. Blame was chiefly attributed to negligence by the driver and flagman of the local train, though the standard signalling routines were also found to be inadequate.

In rail transport, a section could refer to: a portion of a train that may be operated independently and/or combined with other sections to operate as a single unit; or a portion of railway line designated for signalling or maintenance; or an interior portion of a sleeping car made up of two double seats during daytime that convert to two double berths during nighttime.

The Harvey train collision took place on October 12, 1979, when the Shawnee train operated by Amtrak between Carbondale and Chicago Union Station crashed into a parked Illinois Central Gulf freight train, leading to the death of two crew members.

The 1958 Sterlington railroad disaster was a head-on collision by two Erie Railroad trains on August 11, 1958 at 6:47 AM killing 5 people and injuring 22 to 36. The collision occurred when the operator in the signal tower at Suffern failed to hold the westbound train No. 53 at Suffern for the eastbound No. 50 commuter train from Monroe, New York, to Hoboken, New Jersey. When he realized his error, he attempted to contact the crews via radio but was unsuccessful due to a radio dead spot. The trains impacted head-on right in front of the now abandoned Erie Railroad depot in Sterlington, New York near Sloatsburg, killing the crew of the locomotive No. 859 from train No.50 as well as two passengers and injuring the crew of the locomotive No. 1402 from the westbound train.

The Baker Bridge train wreck occurred on November 26, 1905, in Lincoln, Massachusetts, when two passenger trains on the Fitchburg line of the Boston and Maine Railroad were involved in a rear-end collision. Seventeen people were killed in the wreck. Engineer Horace W. Lyons was charged with manslaughter; however, a grand jury chose not to indict him.

The Wollaston disaster was a railroad accident that occurred on October 8, 1878, in the Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy, Massachusetts. 19 people were killed and 170 were injured when an incorrectly placed switch caused the derailment of an excursion train returning from a sporting event. The conductor who placed the switch was convicted of manslaughter, but the conviction was overturned on appeal.

On the evening of January 13, 1882, a southbound New York Central passenger train crashed into the rear of another one stopped on the tracks along Spuyten Duyvil Creek in the similarly named neighborhood of the New York City borough of The Bronx. Eight people were killed, and 19 seriously injured, by the crash and fires afterwards, fires that neighborhood residents and crew extinguished by rolling large snowballs into them until local firefighters arrived. Among the dead was State Senator Webster Wagner, inventor of the sleeping cars used on the train, between two of which he was crushed to death, and a newlywed couple who died together after the bride refused to allow a rescuer to cut her clothing so she could escape. It was the deadliest rail accident in New York City at that time, remaining so for another 20 years.