Muḥammad ibn al-Qāsim al-Thaqafī was an Arab military commander in service of the Umayyad Caliphate who led the Muslim conquest of Sindh, inaugurating the Umayyad campaigns in India. His military exploits led to the establishment of the Islamic province of Sindh, and the takeover of the region from the Sindhi Brahman dynasty and its ruler, Raja Dahir, who was subsequently decapitated with his head sent to al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf in Basra. With the capture of the then-capital of Aror by Arab forces, Muhammad ibn al-Qasim became the first Muslim to have successfully captured Indian land, which marked the beginning of Muslim rule in South Asia.

Multan is a city in Punjab, Pakistan, located on the bank of river Chenab. It is one of the five largest urban centres of Pakistan in 2024 and serves as the administrative centre of Multan Division. A major cultural, religious and economic centre of Punjab region, Multan is one of the oldest inhabited cities of Asia, with a history stretching deep into antiquity.

Abu al-Qasim Mahmud ibn Sabuktigin, usually known as Mahmud of Ghazni or Mahmud Ghaznavi, was Sultan of the Ghaznavid Empire, ruling from 998 to 1030. During his reign and in medieval sources, he is usually known by his honorific Yamin al-Dawla. At the time of his death, his kingdom had been transformed into an extensive military empire, which extended from northwestern Iran proper to the Punjab in the Indian subcontinent, Khwarazm in Transoxiana, and Makran.

Shams al-Din Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Abi Bakr, commonly known by the nisbaal-Maqdisi or al-Muqaddasī was a medieval Arab geographer, author of Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fī maʿrifat al-aqālīm, as well as author of the book, Description of Syria .

The Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent mainly took place between the 13th and the 18th centuries. Earlier Muslim conquests in the subcontinent include the invasions which started in the northwestern subcontinent, especially the Umayyad campaigns during the 8th century. Mahmud of Ghazni, Sultan of the Ghaznavid Empire, preserved an ideological link to the suzerainty of the Abbasid Caliphate and invaded vast parts of Punjab and Gujarat during the 11th century. After the capture of Lahore and the end of the Ghaznavids, the Ghurid ruler Muhammad of Ghor laid the foundation of Muslim rule in India in 1192. In 1202, Bakhtiyar Khalji led the Muslim conquest of Bengal, marking the easternmost expansion of Islam at the time.

Muḥammad Abū’l-Qāsim Ibn Ḥawqal, also known as Abū al-Qāsim b. ʻAlī Ibn Ḥawqal al-Naṣībī, born in Nisibis, Upper Mesopotamia; was a 10th-century Arab Muslim writer, geographer, and chronicler who travelled from AD 943 to 969. His famous work, written in 977, is called Ṣūrat al-’Arḍ. The date of his death, known from his writings, was after AH 368/AD 978.

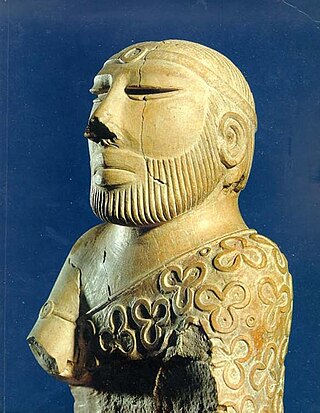

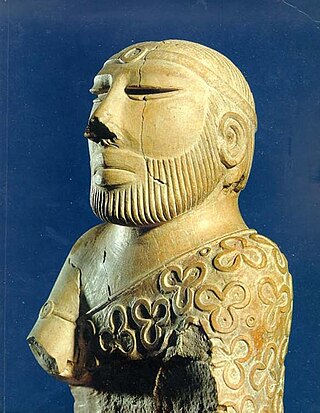

Raja Dahir was the last Hindu ruler of Sindh. A Brahmin ruler, his kingdom was invaded in 711 CE by the Arab Umayyad Caliphate, led by Muhammad bin Qasim, where Dahir died while defending his kingdom. According to the Chachnama, the Umayyad campaign against Dahir was due to a pirate raid off the coast of the Sindhi coast that resulted in gifts to the Umayyad caliph from the king of Serendib being stolen.

Debal was an ancient port located near modern Karachi, Pakistan. It is adjacent to the nearby Manora Island and was administered by Mansura, and later Thatta. Nowadays, it is usually identified with the ruins of Banbhore.

The history of Sindh refers to the history of the Pakistani province of Sindh, as well as neighboring regions that periodically came under its sway.

The Cheraman Juma Mosque is a popular pilgrim centre in Kodungallur in Thrissur district. According to hagiographical legends, it is claimed that the mosque was built in 629 CE by Malik Bin Dinar.

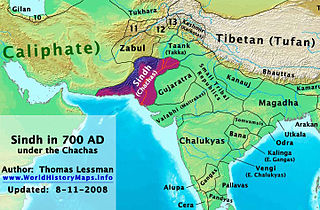

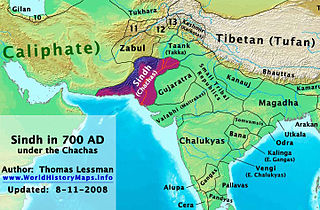

The Umayyad Dynasty came to rule the Caliphate in 661 CE, and during the first half of the 8th century CE, a series of battles took place in the Indian subcontinent between armies of the Umayyad Caliphate and Indian kingdoms situated to the east of the Indus river, subsequent to the Arab conquest of Sindh in present-day Pakistan during 711 – 713 CE.

Medieval Islamic geography and cartography refer to the study of geography and cartography in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. Muslim scholars made advances to the map-making traditions of earlier cultures, particularly the Hellenistic geographers Ptolemy and Marinus of Tyre, combined with what explorers and merchants learned in their travels across the Old World (Afro-Eurasia). Islamic geography had three major fields: exploration and navigation, physical geography, and cartography and mathematical geography. Islamic geography reached its apex with Muhammad al-Idrisi in the 12th century.

Multan, the 4th largest city of Pakistan, in Punjab province is one of the oldest cities in South Asia, though its exact age has yet to be determined. Multan remained the capital and largest city of Punjab region in late ancient and most of the medieval era. The Multan region was centre of many civilizations throughout its history, and has witnessed warfare across millennia because of its location on a major invasion route between South and Central Asia. Multan reached the height of its splendour during the Arab rule of 9th and 10th century when it was made a separate state, the Emirate of Multan, as it controlled large parts of Punjab and Kashmir. It is famous for its Sufi shrines. Multan province was one of the largest and first-established provinces of the Mughal Empire.

The Habbari were an Arab dynasty that ruled much of Greater Sindh, as a semi-independent emirate from 854 to 1024. Beginning with the rule of 'Umar bin Abdul Aziz al-Habbari in 854 CE, the region became semi-independent from the Abbasid Caliphate in 861, while continuing to nominally pledge allegiance to the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad. The Habbari ascension marked the end of a period of direct rule of Sindh by the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, which had begun in 711 CE.

Mansura, referred to as Brahmanabad in later centuries, was the historic capital of the caliphal province of Sindh, during the eighth century under the Umayyad Caliphate and then Abbasid Caliphate from the year 750 AD to 1006 AD. The city was founded as a central garrison by the Umayyad Forces in Sindh, the city transformed into a very vibrant metropolis during the Abbasid Era surpassing the wealth of Multan in the north and Debal in the south. Mansura was the first capital established by the Muslims in the Indian subcontinent after Muhammad bin Qasim seized the Brahmanabad territory. Mansura was built on the shores of the Indus River, it was surrounded by fertile farmland, Ibn Hauqal mentioned the wealthy local merchants who wore Baghdad Costume and were of Sindhi-Arab origins, houses were made of clay, baked bricks and plaster.

Sajāwand is a village in Baraki Barak district, Logar province, Afghanistan.

The Lodi dynasty was the last dynasty to rule over Emirate of Multan, from their capital city of Multan in the 10th century.

The Brahmin dynasty of Sindh, also known as the Chacha dynasty, was the ruling dynasty of the Sindh, succeeding the Rai dynasty. Most of the information about its existence comes from the Chach Nama, a historical account of the Chach-Brahmin dynasty.

Emirate of Multan was a medieval Muslim emirate in Punjab that was centred around city of Multan, present-day part of Punjab, Pakistan. It was initially ruled by the tribe of Banu Munabbih. In 959 CE, Ismaili Qarmatians under Banu Lawi gained control of the Emirate and in 1010, it was conquered by Ghaznavid Empire.

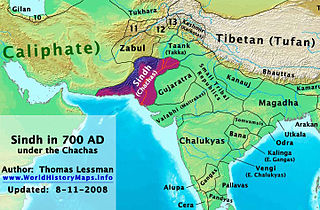

The Umayyad conquest of Sindh took place in 711 AD against the ruling Brahmin dynasty of Sindh and resulted in Sindh being incorporated as a province into the Umayyad Caliphate. The conquest resulted in the overthrow of the last Hindu dynasty of Sindh, the Brahman dynasty, after the death of Raja Dahir.