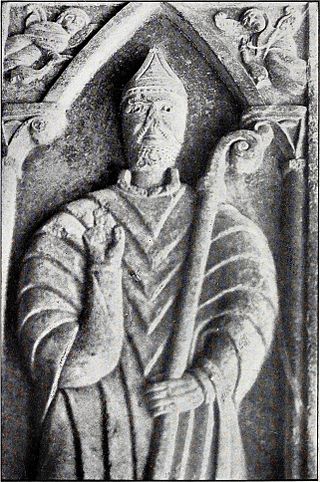

Thomas Becket, also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket, served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then notably as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his death in 1170. He engaged in conflict with Henry II, King of England, over the rights and privileges of the Church and was murdered by followers of the King in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after his death, he was canonised by Pope Alexander III. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion.

Becket or The Honour of God is a 1959 play written in French by Jean Anouilh. It is a depiction of the conflict between Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England leading to Becket's assassination in 1170. It contains many historical inaccuracies, which the author acknowledged.

Robert William Speaight was a British actor and writer, and the brother of George Speaight, the puppeteer.

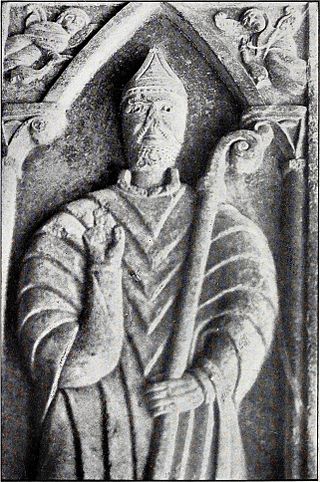

Baldwin of Forde or Ford was Archbishop of Canterbury between 1185 and 1190. The son of a clergyman, he studied canon law and theology at Bologna and was tutor to Pope Eugene III's nephew before returning to England to serve successive bishops of Exeter. After becoming a Cistercian monk he was named abbot of his monastery at Forde and subsequently elected to the episcopate at Worcester. Before becoming a bishop, he wrote theological works and sermons, some of which have survived.

Gilbert Foliot was a medieval English monk and prelate, successively Abbot of Gloucester, Bishop of Hereford and Bishop of London. Born to an ecclesiastical family, he became a monk at Cluny Abbey in France at about the age of twenty. After holding two posts as prior in the Cluniac order he was appointed Abbot of Gloucester Abbey in 1139, a promotion influenced by his kinsman Miles of Gloucester. During his tenure as abbot he acquired additional land for the abbey, and may have helped to fabricate some charters—legal deeds attesting property ownership—to gain advantage in a dispute with the Archbishops of York. Although Foliot recognised Stephen as the King of England, he may have also sympathised with the Empress Matilda's claim to the throne. He joined Matilda's supporters after her forces captured Stephen, and continued to write letters in support of Matilda even after Stephen's release.

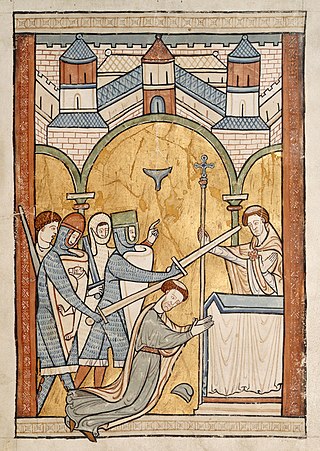

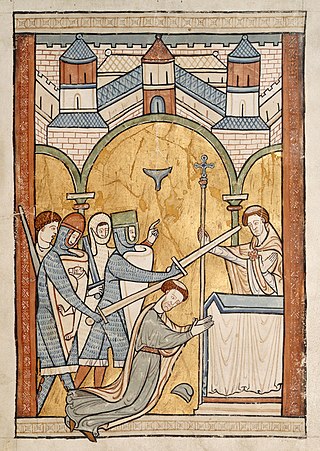

Edward Grim was a monk from Cambridge who visited Canterbury Cathedral on Tuesday 29 December 1170 when Thomas Becket was murdered. He researched and published a book, Vita S. Thomae in about 1180, which is today known chiefly for a short section in which he gave an eyewitness account of the events in the cathedral.

Sir Reginald FitzUrse (1145–1173) was one of the four knights who murdered Thomas Becket in 1170. His name is derived from Fitz, the Anglo-Norman French term meaning "son of" and urse meaning a bear, probable the nom de guerre of his ancestor. Although he lived before the true age of heraldry which developed in the early 13th century, his shield bore the cognizance of a bear, which is visible in a contemporary drawing portraying the murder of Becket.

Sir Hugh de Morville was an Anglo-Norman knight who served King Henry II of England in the late 12th century. He is chiefly famous as one of the assassins of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury in 1170. He held the title Lord of Westmorland and of Knaresborough; his father was Hugh de Morville, Constable of Scotland.

Trinity Chapel at the east end of Canterbury Cathedral forms part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was built under the supervision of the master-masons William of Sens and William the Englishman as a shrine for the relics of St. Thomas Becket. The shrine became one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in England.

Bartholomew of Exeter was a medieval Bishop of Exeter. He came from Normandy and after being a clerk of the Archbishop of Canterbury, was made Archdeacon of Exeter in 1155. He became Bishop of Exeter in 1161. Known for his knowledge of canon law, he was involved in the Becket controversy after the appointment of Thomas Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury. After Becket's death, although he was frequently at the royal court, he mainly attended to his diocese. A number of works by him survive, including sermons and treatises on law and theology.

Events from the 1170s in England.

Henry II ruled as King of England from 1154 to 1189 and at various times he also partially controlled Scotland, Wales, Ireland and the Duchy of Brittany. He has been depicted in various cultural media.

The Becket Casket is a reliquary in Limoges enamel now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It is made of gilt-copper round a wooden core, decorated with champlevé enamel, and of a shape called a "chasse". It was made in about 1180–90 in Limoges, France, and depicts one of the most infamous events in English history. On the night of 29 December 1170, Archbishop Thomas Becket was murdered in Canterbury cathedral by four knights obeying the wishes of King Henry II. It provoked outrage throughout Europe, and pilgrims flocked to Canterbury to pray at the site of the murder. In 1173 Becket was canonized and his shrine was one of the most famous in the Christian world, until its total destruction in 1538 during the reign of Henry VIII. It is thought that this particular casket was made to hold the relics of Thomas Becket that were taken to Peterborough Abbey by Abbot Benedict in 1177. Benedict had been Prior at Canterbury Cathedral and therefore saw Becket's assassination.

Elliott Martin Browne CBE was a British theatre director, known for his production of twentieth century verse plays. He collaborated for many years with T. S. Eliot and was first producer of many of his plays including Murder in the Cathedral.

William of Canterbury (floruit 1170–1177) was a medieval English monk and biographer of Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury murdered in December 1170. He was present at the murder of the archbishop and admitted in his writings that he ran from the murder scene. Later he collected miracle stories about Becket. He also wrote a hagiography, or saint's life, of Becket, one of five written at Canterbury soon after Becket's death. William's hagiography was later used by other medieval writers who wrote about Becket.

Ranulf de Broc was an Anglo-Norman nobleman and royal official during the reign of King Henry II of England. He held two offices in the royal household as well as performing other administrative duties for the king. During the Becket controversy between King Henry and Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, de Broc supported the king and was granted the administration of the exiled archbishop's lands during the later half of the 1160s. This earned de Broc three sentences of excommunication from the archbishop because of de Broc's financial exactions from the estates. De Broc was with the four men who murdered Becket in December 1170, although he did not take part in the actual murder. At de Broc's death around 1179, he left behind a widow and five daughters, who were his co-heiresses.

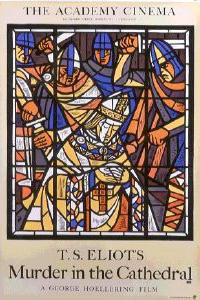

Murder in the Cathedral is a 1951 British drama film directed and produced by George Hoellering and co-written by Hoellering and T. S. Eliot based on Eliot's 1935 verse drama of the same name and starring Father John Groser.

George Michael Hoellering was an Austrian film director, producer and cinema manager. He directed Hortobagy (1936) about the Puszta in Hungary, as well as the 1951 British film Murder in the Cathedral, which he co-wrote with T. S. Eliot. He was the director of the Academy Cinema in London's Oxford Street from 1944 until his death in 1980.

"Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?" is a quote attributed to Henry II of England preceding the death of Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170. While the quote was not expressed as an order, it prompted four knights to travel from Normandy to Canterbury, where they killed Becket. The phrase is commonly used in modern-day contexts to express that a ruler's wish may be interpreted as a command by his or her subordinates. It is also commonly understood as shorthand for any rhetorical device allowing leaders to organise or exhort violence among their followers, either directly or stochastically, while retaining a respectable distance for political, legal, or other reasons.

Saint Thomas Becket window in Chartres Cathedral is a 1215–1225 stained-glass window in Chartres Cathedral, located behind a grille in the Confessors' Chapel, second chapel of the south ambulatory. 8.9 m high by 2.18 m wide, it was funded by the tanners' guild. The furthest left of five lancet windows in the chapel, it is difficult to view and is heavily corroded by glass oxidisation, which has made its left side especially hard to read.