Prehistoric Ukraine, as a part of the Pontic steppe in Eastern Europe, played an important role in Eurasian cultural events, including the spread of the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages, Indo-European migrations, and the domestication of the horse.

The coat of arms of Ukraine is a blue shield with a golden trident. It is colloquially known as the tryzub.

The Central Rada of Ukraine, also called the Central Council, was the All-Ukrainian council that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputies as well as few members of political, public, cultural and professional organizations of the Ukrainian People's Republic. After the All-Ukrainian National Congress, the Council became the revolutionary parliament in the interbellum lasting until the Ukrainian-Soviet War. Unlike many other councils in the Russian Republic, bolshevization of this council failed completely, prompting the Bolsheviks in Ukraine to relocate to Kharkov.

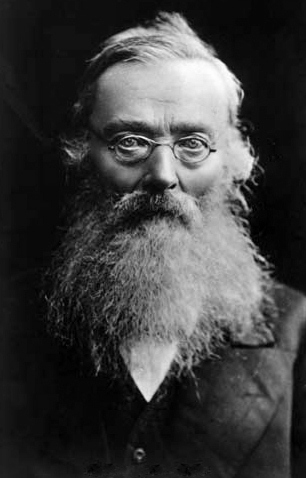

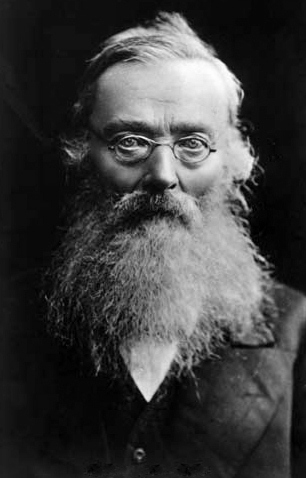

Mykola Ivanovych Kostomarov or Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov was one of the most distinguished Russo–Ukrainian historians, one of the first anti-Normanists, and the father of modern Ukrainian historiography, a Professor of Russian History at the St. Vladimir University of Kiev and later at the St. Petersburg University, an Active State Councillor of Russia, an author of many books, including his famous biography of the seventeenth century Hetman of Zaporozhian Cossacks Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the research on the Ataman of Don Cossacks Stepan Razin and his fundamental 3-volume Russian History in Biographies of its main figures.

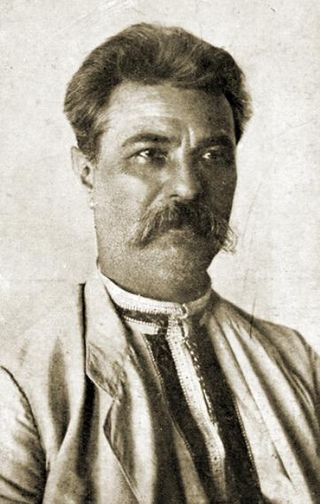

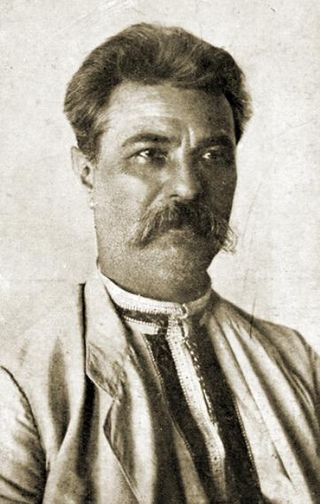

Volodymyr Kyrylovych Vynnychenko was a Ukrainian statesman, political activist, writer, playwright and artist who served as the first prime minister of the Ukrainian People's Republic.

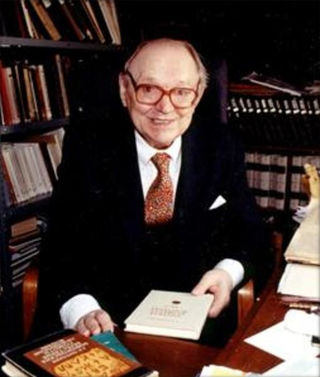

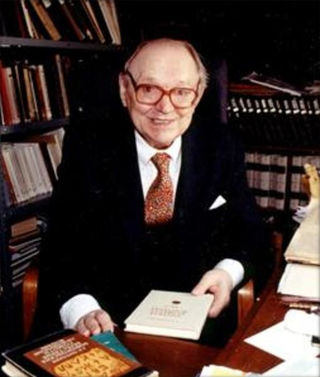

Omeljan Yosypovych Pritsak was the first Mykhailo Hrushevsky Professor of Ukrainian History at Harvard University and the founder and first director (1973–1989) of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.

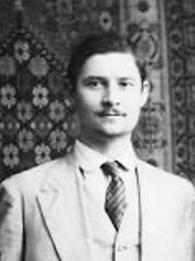

Dmytro Ivanovych Doroshenko was a prominent Ukrainian political figure during the revolution of 1917–1918 and a leading Ukrainian emigre historian during the inter-war period. Doroshenko was a supporter of federal ties with the Russian Republic and a member of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Federalists.

Oleksander Petrovych Ohloblyn was a Ukrainian politician and historian who served as mayor of Kyiv while it was under the occupation of Nazi Germany in 1941. He was one of the most important Ukrainian émigré historians of the Cold War era.

Various factions fought over Ukrainian territory after the collapse of the Russian Empire following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and after the First World War ended in 1918, resulting in the collapse of Austria-Hungary, which had ruled Ukrainian Galicia. The crumbling of the empires had a great effect on the Ukrainian nationalist movement, and in a short period of four years a number of Ukrainian governments sprang up. This period was characterized by optimism and by nation-building, as well as by chaos and civil war. Matters stabilized somewhat in 1921 with the territory of modern-day Ukraine divided between Soviet Ukraine and Poland, and with small ethnic-Ukrainian regions belonging to Czechoslovakia and to Romania.

Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party was a political party in Ukraine and the Russian Republic founded in April 1917, based on separate groups and circles of SRs that existed on the territory of Ukraine since 1905. The left faction of the party dissolved it in 1918 forming a new party, while the Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party was recreated in January 1919 by its moderate faction members.

The Ukrainian War of Independence, also referred to as the Ukrainian–Soviet War in Ukraine, lasted from March 1917 to November 1921. It saw the establishment and development of an independent Ukrainian republic, most of which was absorbed into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic between 1919 and 1920. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union between 1922 and 1991.

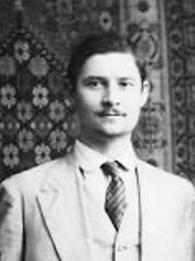

Serhiy Yefremov was a Ukrainian literary journalist, historian, critic, political activist, statesman, and academician. He was a member of the Ukrainian Academy of Science (1919) and Shevchenko Scientific Society in Lviv.

The General Secretariat of Ukraine was the autonomous Ukrainian executive government of the Russian Republic from June 28, 1917, to January 22, 1918. For most of its existence it was headed by Volodymyr Vynnychenko.

Pavlo Onkiiovych Khrystiuk was a Ukrainian cooperator, historian, journalist, political activist, and statesman.

Serhii Mykolayovych Plokhy is the Mykhailo Hrushevsky professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard University, where he also serves as the director of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.

The Ukrainian–Soviet War is the term commonly used in post-Soviet Ukraine for the events taking place between 1917 and 1921, nowadays regarded essentially as a war between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Bolsheviks. The war ensued soon after the October Revolution when Lenin dispatched Antonov's expeditionary group to Ukraine and Southern Russia.

The Little Russian identity was a cultural, political, and ethnic self-identification of a population of Ukraine who aligned themselves as one of the constituent parts of the triune Russian nationality. The Little Russian identity combined the cultures of Imperial Russia and Cossack Hetmanate.

Mykhailo Hrushevskyi Street or simply Hrushevskyi Street is a street in central Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine.

History of Ukraine-Rusʹ is a monumental 10-volume monographic series by Mykhailo Hrushevsky. The work is generally considered a magnum opus and a foundation of the contemporary history of Ukraine. It covers the period from ancient times to the second half of the 17th century. It was written between 1895 and 1933.

The Third Universal of the Ukrainian Central Council is a state-political act, universal of the Central Council of Ukraine, proclaiming the formation of the Ukrainian People's Republic. Accepted 20 November [O.S. 7 November] 1917 in November in Kyiv.