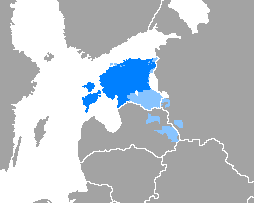

Estonian is a Uralic language of the Finnic branch spoken in Estonia. It is the official language of Estonia, spoken natively by about 1.1 million people; 922,000 people in Estonia and 160,000 outside Estonia. It is a Southern Finnic language and is the second-most-spoken language among all the Finnic languages.

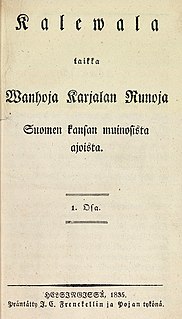

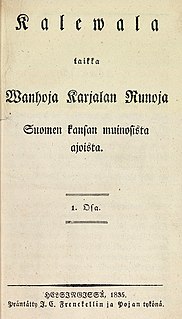

The Kalevala is a 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology, telling an epic story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies and retaliatory voyages between the peoples of the land of Kalevala called Väinölä and the land of Pohjola and their various protagonists and antagonists, as well as the construction and robbery of the mythical wealth-making machine Sampo.

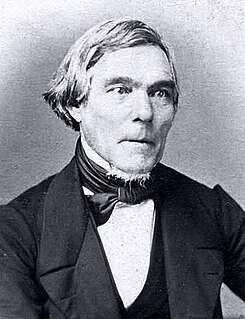

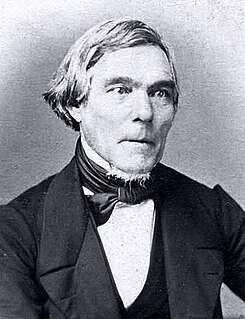

Elias Lönnrot was a Finnish physician, philologist and collector of traditional Finnish oral poetry. He is best known for creating the Finnish national epic, Kalevala, (1835, enlarged 1849), from short ballads and lyric poems gathered from the Finnish oral tradition during several expeditions in Finland, Russian Karelia, the Kola Peninsula and Baltic countries.

Finnish mythology is a commonly applied description of the folklore of Finnish paganism, of which a modern revival is practiced by a small percentage of the Finnish people. It has many features shared with Estonian and other Finnic mythologies, but also shares some similarities with neighbouring Baltic, Slavic and, to a lesser extent, Norse mythologies.

Ilmarinen, the Eternal Hammerer, blacksmith and inventor in the Kalevala, is a god and archetypal artificer from Finnish mythology. He is immortal and capable of creating practically anything, but is portrayed as being unlucky in love. He is described as working the known metals of the time, including brass, copper, iron, gold, and silver. The great works of Ilmarinen include the crafting of the dome of the sky and the forging of the Sampo. His usual epithet in the Kalevala is seppo, a poetic word for "smith". and the source of the given name Seppo.

Pohjola, sometimes just Pohja, is a location in Finnish mythology. It is one of the two main polarities in the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, along with Kalevala or Väinölä.

Kvenland, known as Cwenland, Qwenland, Kænland or similar terms in medieval sources, is an ancient name for an area in Fennoscandia and Scandinavia. Kvenland, in that or nearly that spelling, is known from an Old English account written in the 9th century, which used the information provided by the Norwegian adventurer and traveler Ohthere, and from Nordic sources, primarily Icelandic. One possible additional source was written in the modern-day area of Norway — all the known Nordic sources date to the 12th and 13th centuries. Other possible references to Kvenland by other names or spellings are also discussed on this page.

Henrik Gabriel Porthan was a professor and rector at the Royal Academy of Turku. He was a scholar sometimes known as The Father of Finnish History.

Finnish literature refers to literature written in Finland. During the European early Middle Ages, the earliest text in a Finnic language is the unique thirteenth-century Birch bark letter no. 292 from Novgorod. The text was written in Cyrillic and represented a dialect of Finnic language spoken in Russian Olonets region. The earliest texts in Finland were written in Swedish or Latin during the Finnish Middle Age. Finnish-language literature was slowly developing from the 16th century onwards, after written Finnish was established by the Bishop and Finnish Lutheran reformer Mikael Agricola (1510–1557). He translated the New Testament into Finnish in 1548.

Kaleva – also known as Kalevi or Kalev – and his sons are important heroic figures in Estonian, Finnish and Karelian mythology. In the Finnish epic Kalevala, he is an ancient Finnish ruler. In Estonian mythology and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald's epic poem Kalevipoeg, King Kalev was the father of King Kalevipoeg and the husband of Linda.

Estonian literature is literature written in the Estonian language The domination of Estonia after the Northern Crusades, from the 13th century to 1918 by Germany, Sweden, and Russia resulted in few early written literary works in the Estonian language. The oldest records of written Estonian date from the 13th century. Originates Livoniae in Chronicle of Henry of Livonia contains Estonian place names, words and fragments of sentences. The Liber Census Daniae (1241) contains Estonian place and family names. The earliest extant samples of connected Estonian are the so-called Kullamaa prayers dating from 1524 and 1528. The first known printed book is a bilingual German-Estonian translation of the Lutheran catechism by S.Wanradt and J. Koell (1535). For the use of priests an Estonian grammar was printed in German in 1637. The New Testament was translated into southern Estonian in 1686. The two dialects were united by Anton Thor Helle in a form based on northern Estonian. Writings in Estonian became more significant in the 19th century during the Estophile Enlightenment Period (1750–1840).

Kristian Jaak Peterson also known as Christian Jacob Petersohn, was an Estonian poet, commonly regarded as a herald of Estonian national literature and the founder of modern Estonian poetry. He died of tuberculosis aged 21.

The earliest mentioning of Estonian singing dates back to Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum. Saxo spoke of Estonian warriors who sang at night while waiting for a battle. Henry of Livonia at the beginning of the 13th century described Estonian sacrificial customs, gods and spirits. In 1578 Balthasar Russow described the celebration of midsummer (jaanipäev), the St. John's Day by Estonians. In 1644 Johann Gutslaff spoke of the veneration of holy springs and J.W. Boecler described Estonian superstitious beliefs in 1685. Estonian folklore and beliefs including samples of folk songs appear in Topographische Nachrichten von Liv- und Estland by August W. Hupel in 1774–82. J.G von Herder published seven Estonian folk songs, translated into German in his Volkslieder in 1778 and republished as Stimmen der Völker in Liedern in 1807.

Cristfried Ganander was a Finnish compiler of folk culture, a priest and an 18th-century lexicographer. Ganander's greatest achievement was the compilation of the first fully extensive Finnish-language dictionary which was, however, unpublished. He was also a collector of folk culture well before Elias Lönnrot. His most well-known published work is Mythologia Fennica in 1789, a reference book of folk religion. He also published some poetry and worked as a teacher.

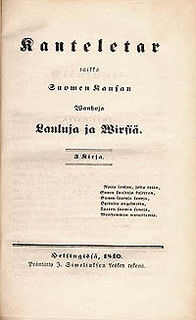

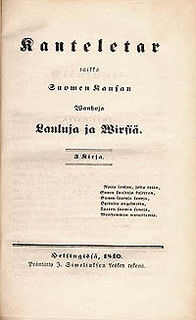

Kanteletar is a collection of Finnish folk poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot. It is considered to be a sister collection to the Finnish national epic Kalevala. The poems of Kanteletar are based on the trochaic tetrameter, generally referred to as "Kalevala metre".

In Finnish folklore, Hymylä is a mysterious place for the banishment of a child who failed in a children's game, usually, the game of riddles.

Synty is an important concept in Finnish mythology. Syntysanat ('origin-words') or syntyloitsut ('origin-charms') provide an explanatory, mythical account of the origin of a phenomenon, material, or species, and were an important part of traditional Finno-Karelian culture, particularly in healing rituals. Although much in the Finnish traditional charms is paralleled elsewhere, 'the role of aetiological and cosmogonic myths' in Finnic tradition 'appears exceptional in Eurasia'. The major study remains that by Kaarle Krohn, published in 1917.

The corpus of traditional riddles from the Finnic-speaking world is fairly unitary, though eastern Finnish-speaking regions show particular influence of Russian Orthodox Christianity and Slavonic riddle culture. The Finnish for 'riddle' is arvoitus, related to the verb arvata ('guess').

Ancient kings of Finland are kings of Finland mentioned in early historical sources. The word kuningas is an old Finnic word deriving from the ancient Germanic word kuningaz. In the time the sources were written, "Finland" mainly referred to the Finland Proper area, and depending on the source, the "kings of Finland" could also refer to kings of the Sami people.

Väki is a supernatural power in Finnish mythology. It was believed by Baltic Fins that väki resided in natural sites, objects, and animals. Väki has been compared to mana. However, according to Laura Stark, väki is about a impersonal power rather than a universal force. Väki has also been compared to orenda.