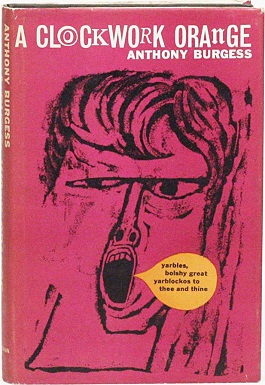

A Clockwork Orange is a dystopian satirical black comedy novel by English writer Anthony Burgess, published in 1962. It is set in a near-future society that has a youth subculture of extreme violence. The teenage protagonist, Alex, narrates his violent exploits and his experiences with state authorities intent on reforming him. The book is partially written in a Russian-influenced argot called "Nadsat", which takes its name from the Russian suffix that is equivalent to '-teen' in English. According to Burgess, the novel was a jeu d'esprit written in just three weeks.

Rhyming slang is a form of slang word construction in the English language. It is especially prevalent among Cockneys in England, and was first used in the early 19th century in the East End of London; hence its alternative name, Cockney rhyming slang. In the US, especially the criminal underworld of the West Coast between 1880 and 1920, rhyming slang has sometimes been known as Australian slang.

A Slang is a vocabulary of an informal register, common in verbal conversation but avoided in formal writing. It also sometimes refers to the language generally exclusive to the members of particular in-groups in order to establish group identity, exclude outsiders, or both. The word itself came about in the 18th century and has been defined in multiple ways since its conception.

John Anthony Burgess Wilson, who published under the name Anthony Burgess, was a British writer and composer.

In linguistics, a neologism is any relatively recent and isolated term, word, or phrase that nevertheless has achieved popular or institutional recognition, and is becoming accepted into mainstream language. Most definitively, a word can be considered a neologism once it is published in a dictionary.

A cant is the jargon or language of a group, often employed to exclude or mislead people outside the group. It may also be called a cryptolect, argot, pseudo-language, anti-language or secret language. Each term differs slightly in meaning; their uses are inconsistent. Richard Rorty defines cant by saying that "'Cant', in the sense in which Samuel Johnson exclaims, 'Clear your mind of cant,' means, in other words, something like that which 'people usually say without thinking, the standard thing to say, what one normally says'." In Heideggerian terms it is what "das Man" says.

Alex is a fictional character in Anthony Burgess' novel A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick's film adaptation of the same name, in which he is played by Malcolm McDowell. In the book, Alex's surname is not stated. In the film, however, Kubrick chose it to be DeLarge, a reference to Alex calling himself The Large in the novel. Later on in the film, two newspaper articles print his name as "Alex Burgess", a reference to Anthony Burgess. In addition to the book and film, Alex was portrayed by Vanessa Claire Smith in the ARK Theatre Company's multimedia adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, directed by Brad Mays.

Runglish, Ruslish, Russlish, or Russian English, is a term describing a language born out of a mixture of the English and Russian languages. This is common among Russian speakers who speak English as a second language, and it is mainly spoken in post-Soviet States.

A Clockwork Orange is a 1971 dystopian crime film adapted, produced, and directed by Stanley Kubrick, based on Anthony Burgess's 1962 novel of the same name. It employs disturbing, violent images to comment on psychiatry, juvenile delinquency, youth gangs, and other social, political, and economic subjects in a dystopian near-future Britain.

Caló is an argot or slang of Mexican Spanish that originated during the first half of the 20th century in the Southwestern United States. It is the product of zoot-suit pachuco culture that developed in the 1930s and '40s in cities along the US/Mexico border.

Poglish, also known as Polglish and Ponglish, is a blend of two words from Polish and English. It is the product of macaronically mixing Polish- and English-language elements within a single speech production, or the use of "false friends" or of cognate words in senses that have diverged from those of the common etymological root. Such combining or confusion of Polish and English elements, when it occurs within a single word, term, or phrase, may, inadvertently or deliberately, produce a neologism.

Ein kleines bisschen Horrorschau is the sixth LP by Die Toten Hosen, released in 1988. This is considered by the band as the best DTH album as of 1988.

"Never Gonna Stop " is a promotional single taken from Rob Zombie's second album The Sinister Urge. The song can also be found on Zombie's Past, Present & Future and The Best of Rob Zombie. It was nominated for the Grammy for Best Metal Performance for the 2003 Grammy Awards Ceremony, but lost to Korn's "Here to Stay".

Moog Droog is the second EP by the Super Furry Animals. It was originally released in October 1995 by the Welsh label Ankst Records, and reissued in May 1997. The two releases have different covers: the original version depicts a faceless humanoid brushing dust under a carpet, while the "export" version simply has a red/orange bear drawn on a blue background.

Horror Show may refer to:

Swardspeak is an argot or cant slang derived from Taglish and used by a number of LGBT people in the Philippines.

"Girl Loves Me" is a song by English musician David Bowie. It is the fifth track on Bowie's twenty-sixth and final studio album, Blackstar, released on 8 January 2016. The track was written by Bowie and produced by Bowie and Tony Visconti. "Girl Loves Me" peaked at number 87 on the Dutch Top 100 and number 146 on the UK Singles Chart.