Related Research Articles

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

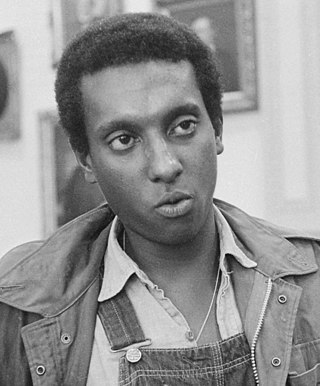

Kwame Ture was an American organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad in the Caribbean, he grew up in the United States from the age of 11 and became an activist while attending the Bronx High School of Science. He was a key leader in the development of the Black Power movement, first while leading the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), then as the "Honorary Prime Minister" of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and last as a leader of the All-African People's Revolutionary Party (A-APRP).

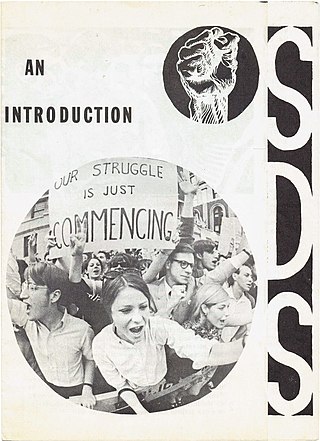

The Port Huron Statement is a 1962 political manifesto of the American student activist movement Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). It was written by SDS members, and completed on June 15, 1962, at a United Auto Workers (UAW) retreat outside of Port Huron, Michigan, for the group's first national convention. Under Walter Reuther's leadership, the UAW paid for a range of expenses for the 1962 convention, including use of the UAW summer retreat in Port Huron.

Thomas Emmet Hayden was an American social and political activist, author, and politician. Hayden was best known for his role as an anti-war, civil rights, and intellectual activist in the 1960s, becoming an influential figure in the rise of the New Left. As a leader of the leftist organization Students for a Democratic Society, he authored the Port Huron Statement, helped lead protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and stood trial in the resulting "Chicago Seven" case.

Mary Elizabeth King is a professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at the United Nations affiliated University for Peace, a political scientist, and author of several publications. She is a graduate of Ohio Wesleyan University and received a doctorate in international politics from Aberystwyth University in 1999. She is also a Fellow of the Rothermere American Institute and a distinguished Scholar at the American University Center for Global Peace in Washington D.C.

James Forman was a prominent African-American leader in the civil rights movement. He was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. As the executive secretary of SNCC from 1961 to 1966, Forman played a significant role in the Freedom Rides, the Albany movement, the Birmingham campaign, and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

The United States Student Press Association (USSPA) was a national organization of campus newspapers and editors active in the 1960s. A program of the National Student Association (NSA), the USSPA formed a national news agency for college publications called Collegiate Press Service.

Collegiate Press Service, also called College Press Service (CPS), was a news agency supplying stories to student newspapers. It operated under various owners and names from 1962 to c. 1999.

Robert Alan Haber is an American activist. In 1960 he was elected the first president of the now-defunct Students for a Democratic Society, a left-wing student activist organization. FBI files at the time indicated his official title as Field Secretary. Described variously at the time as "Ann Arbor's resident radical" and "reticent visionary", Haber organized a human rights conference in April of that year which "marked the debut of SDS" and invited four organizers of the 1960 NAACP sit-ins against segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Project MINARET was a domestic espionage project operated by the National Security Agency (NSA), which, after intercepting electronic communications that contained the names of predesignated US citizens, passed them to other government law enforcement and intelligence organizations. Intercepted messages were disseminated to the FBI, CIA, Secret Service, Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), and the Department of Defense. The project was a sister project to Project SHAMROCK.

Theodore "Ted" Gold was a member of Weather Underground who died in the 1970 Greenwich Village townhouse explosion.

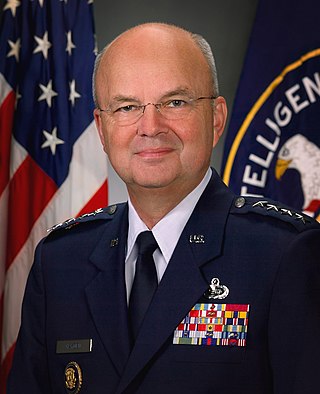

Michael Vincent Hayden is a retired United States Air Force four-star general and former Director of the National Security Agency, Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence, and Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. He also serves as a professor at the George Mason University – Schar School of Policy and Government. Hayden currently co-chairs the Bipartisan Policy Center's Electric Grid Cyber Security Initiative.

Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from its earliest days in 1960 until her death in October 1967. She served the organization as an activist in the field and as an administrator in the Atlanta central office. She eventually succeeded James Forman as SNCC's executive secretary and was the only woman ever to serve in this capacity. She was well respected by her SNCC colleagues and others within the movement for her work ethic and dedication to those around her. SNCC Freedom Singer Matthew Jones recalled, "You could feel her power in SNCC on a daily basis". Jack Minnis, director of SNCC's opposition research unit, insisted that people could not fool her. Over the course of her life, she served 100 days in prison for the movement.

The United States Youth Council (USYC) was a nonprofit coalition of organizations which served youth and young adults in the United States. It was founded in 1945 by the National Social Welfare Assembly as that organization's youth division, but became independent in the early 1960s. In 1967, The New York Times revealed that the USYC had received more than 90 percent of its funds from the Central Intelligence Agency, leading many of the organization's largest members to quit. USYC continued to receive funding from the United States government before disbanding in 1986.

The Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC) was a student activist group in the southern United States during the 1960s, which focused on many political and social issues including: African-American civil rights, opposition to the Vietnam War, workers' rights, and feminism. It was intended, in part, to be Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) for Southerners and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) for white students – at a time when it was dangerous for SDS to attempt to organize in the Deep South and when SNCC was starting to discuss expelling white volunteers. It was felt that students at the traditionally white and black colleges in the South could be more effectively organized separately than in an integrated student civil rights organization; however, this was controversial and initially opposed by advisors like Anne Braden. Sue Thrasher and Archie Allen of the Christian Action Fellowship were among the founders of the group, with the support of Bob Moses and others. At its inception, the group had close ties to controversial Louisville, Kentucky radicals Carl and Anne Braden and their organization, the Southern Conference Education Fund, but a deliberate effort was later made to put some distance between the SSOC and the Bradens to avoid the appearance that the SSOC was a Communist front.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships and parliamentary procedure, the founders conceived of the organization as a broad exercise in "participatory democracy". From its launch in 1960 it grew rapidly in the course of the tumultuous decade with over 300 campus chapters and 30,000 supporters recorded nationwide by its last national convention in 1969. The organization splintered at that convention amidst rivalry between factions seeking to impose national leadership and direction, and disputing "revolutionary" positions on, among other issues, the Vietnam War and Black Power.

The League for Industrial Democracy (LID) was founded as a successor to the Intercollegiate Socialist Society in 1921. Members decided to change its name to reflect a more inclusive and more organizational perspective.

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as feminism, gay rights, drug policy reforms and the rejection of traditional family values, social order, and gender roles. The New Left differs from the traditional left in that it tended to acknowledge the struggle for various forms of social justice, whereas previous movements prioritized explicitly economic goals. However, many have used the term "New Left" to describe an evolution, continuation, and revitalization of traditional leftist goals.

Sandra Cason Hayden was an American radical student activist and civil rights worker in the 1960s. Recognized for her defense of direct action in the struggle against racial segregation, in 1960 she was an early recruit to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). With Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi, Hayden was a strategist and organizer for the 1964 Freedom Summer. In the internal discussion that followed its uncertain outcome, she clashed with the SNCC national executive.

Gwendolyn Marie Patton was a prominent civil rights activist and educator. Patton’s first steps into the civil rights movement were with the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) where she helped African Americans register to vote with her grandparents. During this time, she also participated in the Montgomery bus boycott. After her time with the MIA, Patton could be seen working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Tuskegee University and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Following her time at Tuskegee University, she assisted in establishing both anti-war and human rights organizations that furthermore supported the feminist and Black Power movements, as well as communism, the Cuban Revolution, and marxism. In the 1984 presidential debates, she started her political career as a delegate for Jesse Jackson’s campaign. Then in 1986 as a candidate for Alabama legislature, and finally in 1992 in the U.S. Senate. Patton was also a historian, which helped her to construct the H. Councill Trenholm State Technical College, which is now called the Trenholm State Community College.

References

Citations

- ↑ "United States National Student Association Collection | Berea College Special Collections and Archives Catalog". berea.libraryhost.com. Berea College. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ "Teen‐Agers Who Plan to Spend the Summer Abroad Are Offered a Wide Choice of Travel Programs". The New York Times. May 13, 1964. p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Johnston, Angus. "A Brief History of NSA and USSA". United States Student Association. Archived from the original on Nov 8, 2023.

- ↑ "AID TO NEGRO SEEN AS HELP TO NATION; National Student Association Convention Told Assistance Would Benefit Democracy". The New York Times. Sep 2, 1947. p. 22.

- ↑ "ALGERIANS TO AID RED YOUTH FORUM; Student Group's Plan Seen as Move Toward Soviet". The New York Times. Aug 25, 1964. p. 2.

- ↑ Warner, Michael (June 2008). "'The Mighty Wurlitzer': How the CIA Played America [book review]". Intelligence in Recent Public Literature. Studies in Intelligence. 52 (2). Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency: 71–73. ISSN 1527-0874. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

'Who co-opted whom?' was a little joke whispered by former officers of the National Student Association once they joined CIA to run Covert Action Staff's Branch 5 – and thus took over the youth and student field in the Agency's larger campaign.

- ↑ De Vries, T. (2012). "The 1967 Central Intelligence Agency Scandal: Catalyst in a Transforming Relationship between State and People". The Journal of American History . 98 (4): 1075–1092. doi:10.1093/jahist/jar563.

- ↑ "Secret Subsidizing of National Student Association By Central Intelligence Agency Congressional Record" (PDF). www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/. CIA. 15 February 1967. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ↑ Casey, Hayden (1960). "Speech in support of the sit-ins by Casey Hayden, United States National Student Association conference, August 1960". www.crmvet.org. Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ↑ Houck, Davis W.; Dixon, David E., eds. (2008). "Casey Hayden: August 1960, National Student Association Convention, Minneapolis, Minnesota". Women and the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1965. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604737608.

- ↑ Smith, Harold L. (2015). "Casey Hayden: Gender and the Origins of SNCC, SDS, and the Women's Liberation Movement". In Turner, Elizabeth Hayes; Cole, Stephanie; Sharpless, Rebecca (eds.). Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives. University of Georgia Press. p. 365. ISBN 9780820347905.

- ↑ "RIGHTS MOVEMENT STIRS STUDENTS; Thousands Planning Active Roles for the Summer". The New York Times. March 8, 1964. p. 61.

- ↑ "Dr. King Asks Fast For Needy Negroes In the Deep South". The New York Times. Nov 7, 1964. p. 56.

- 1 2 "National Student Group Plans A 5‐Year Drive for Local Units". The New York Times. Aug 20, 1972.

- ↑ Stern, Sol (March 1967). "NSA and the CIA". Ramparts. pp. 29–39.

- ↑ Onis, Juan de (1967-02-16). "Ramparts Says C.I.A. Received Student Report; Magazine Declares Agency Turned Group It Financed Into an 'Arm of Policy'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ↑ Vries, Tity de (2012). "The 1967 Central Intelligence Agency Scandal: Catalyst in a Transforming Relationship between State and People". Journal of American History. 98 (4): 1075–1092. doi:10.1093/jahist/jar563.

- ↑ "ANTI-COMMUNIST WORK OF NATIONAL STUDENTS ASSOCIATION | CIA FOIA (foia.cia.gov)". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ Wilford 2008 , p. 4: "The last tie between the NSA and the CIA was severed in August 1967, when the student group took over the title and mortgage payments on the Washington brownstone that had served as its headquarters since 1965."

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (March 16, 2015). "Curtis Gans, 77, Is Dead; Worked to Defeat President Johnson". The New York Times.

He was introduced to student activism through the civil rights movement and eventually became national affairs vice president of the National Student Association. (He was among the association's officers who demanded an accounting of subsidies it had surreptitiously received from the Central Intelligence Agency.)

- 1 2 HECHINGER, FRED M. (Aug 31, 1969). "Education; Deep Trouble in the National Student Association". p. 129.

- ↑ Ripley, Anthony (Aug 26, 1971). "Student Group Rejects Blacks' Demand for Payments". The New York Times.

- ↑ Ripley, Anthony (Aug 29, 1971). "First Woman President Heads National Student Association". The New York Times. p. 48.

- 1 2 Edwards, Julia (July 18, 2012). "The Hollywood Connection". National Journal. Archived from the original on Aug 2, 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Finke, Nikki (August 13, 1989). "A Radical Move: Margery Tabankin Has Fled the Center of Power for the Center of Status, but Without Missing an Activist Beat". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Johnston, J. Angus (2009). "The United States National Student Association: Democracy, Activism, and the Idea of the Student, 1947–1978" (PDF). City University of New York.

- ↑ "N.S.A. to Hold Parley With Foreign Students". The New York Times. Oct 7, 1971. p. 25.

- ↑ "Student Group Visits Hanoi". The New York Times. May 23, 1972. p. 15.

References and further reading

- Paget, Karen M. (2015). Patriotic Betrayal: The Inside Story of the CIA's Secret Campaign to Enroll American Students in the Crusade against Communism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300205084.

- Schwartz, Eugene G., ed. (2006). Founding the National Student Association After World War II: an Anthology and Sourcebook. American Students Organize. ISBN 9780275991005.

- Wilford, Hugh (2008). The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02681-0.