Related Research Articles

A concept is defined as an abstract idea. It is understood to be a fundamental building block underlying principles, thoughts and beliefs. Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach, cognitive science.

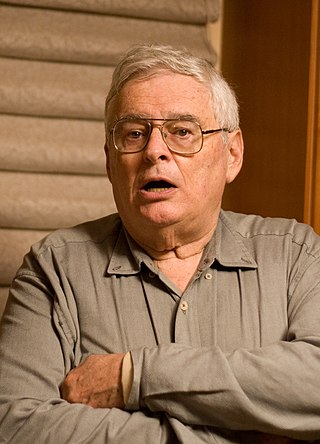

Daniel Clement Dennett III is an American philosopher, writer, and cognitive scientist whose research centers on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science.

The mind is that which thinks, imagines, remembers, wills, and senses, or is the set of faculties responsible for such phenomena. The mind is also associated with experiencing perception, pleasure and pain, belief, desire, intention, and emotion. The mind can include conscious and non-conscious states as well as sensory and non-sensory experiences.

A belief is a subjective attitude that a proposition is true or a state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some stance, take, or opinion about something. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false. To believe something is to take it to be true; for instance, to believe that snow is white is comparable to accepting the truth of the proposition "snow is white". However, holding a belief does not require active introspection. For example, few carefully consider whether or not the sun will rise tomorrow, simply assuming that it will. Moreover, beliefs need not be occurrent, but can instead be dispositional.

Intentionality is the power of minds to be about something: to represent or to stand for things, properties and states of affairs. Intentionality is primarily ascribed to mental states, like perceptions, beliefs or desires, which is why it has been regarded as the characteristic mark of the mental by many philosophers. A central issue for theories of intentionality has been the problem of intentional inexistence: to determine the ontological status of the entities which are the objects of intentional states.

In philosophy of mind, functionalism is the thesis that each and every mental state is constituted solely by its functional role, which means its causal relation to other mental states, sensory inputs, and behavioral outputs. Functionalism developed largely as an alternative to the identity theory of mind and behaviorism.

Eliminative materialism is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind. It is the idea that the majority of mental states in folk psychology do not exist. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since they are poorly defined. The argument is that psychological concepts of behavior and experience should be judged by how well they reduce to the biological level. Other versions entail the nonexistence of conscious mental states such as pain and visual perceptions.

Jerry Alan Fodor was an American philosopher and the author of many crucial works in the fields of philosophy of mind and cognitive science. His writings in these fields laid the groundwork for the modularity of mind and the language of thought hypotheses, and he is recognized as having had "an enormous influence on virtually every portion of the philosophy of mind literature since 1960." At the time of his death in 2017, he held the position of State of New Jersey Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, at Rutgers University, and had taught previously at the City University of New York Graduate Center and MIT.

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them. A theory of mind includes the knowledge that others' beliefs, desires, intentions, emotions, and thoughts may be different from one's own. Possessing a functional theory of mind is considered crucial for success in everyday human social interactions. People utilise a theory of mind when analyzing, judging, and inferring others' behaviors. The discovery and development of theory of mind primarily came from studies done with animals and infants. Factors including drug and alcohol consumption, language development, cognitive delays, age, and culture can affect a person's capacity to display theory of mind. Having a theory of mind is similar to but not identical with having the capacity for empathy or sympathy.

The language of thought hypothesis (LOTH), sometimes known as thought ordered mental expression (TOME), is a view in linguistics, philosophy of mind and cognitive science, forwarded by American philosopher Jerry Fodor. It describes the nature of thought as possessing "language-like" or compositional structure. On this view, simple concepts combine in systematic ways to build thoughts. In its most basic form, the theory states that thought, like language, has syntax.

The intentional stance is a term coined by philosopher Daniel Dennett for the level of abstraction in which we view the behavior of an entity in terms of mental properties. It is part of a theory of mental content proposed by Dennett, which provides the underpinnings of his later works on free will, consciousness, folk psychology, and evolution.

Here is how it works: first you decide to treat the object whose behavior is to be predicted as a rational agent; then you figure out what beliefs that agent ought to have, given its place in the world and its purpose. Then you figure out what desires it ought to have, on the same considerations, and finally you predict that this rational agent will act to further its goals in the light of its beliefs. A little practical reasoning from the chosen set of beliefs and desires will in most instances yield a decision about what the agent ought to do; that is what you predict the agent will do.

Semantic holism is a theory in the philosophy of language to the effect that a certain part of language, be it a term or a complete sentence, can only be understood through its relations to a larger segment of language. There is substantial controversy, however, as to exactly what the larger segment of language in question consists of. In recent years, the debate surrounding semantic holism, which is one among the many forms of holism that are debated and discussed in contemporary philosophy, has tended to centre on the view that the "whole" in question consists of an entire language.

In philosophy of mind, the computational theory of mind (CTM), also known as computationalism, is a family of views that hold that the human mind is an information processing system and that cognition and consciousness together are a form of computation. Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts (1943) were the first to suggest that neural activity is computational. They argued that neural computations explain cognition. The theory was proposed in its modern form by Hilary Putnam in 1967, and developed by his PhD student, philosopher, and cognitive scientist Jerry Fodor in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. It was vigorously disputed in analytic philosophy in the 1990s due to work by Putnam himself, John Searle, and others.

A mental representation, in philosophy of mind, cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science, is a hypothetical internal cognitive symbol that represents external reality or its abstractions.

David Papineau is a British academic philosopher, born in Como, Italy. He works as Professor of Philosophy of Science at King's College London and the City University of New York Graduate Center, and previously taught for several years at Cambridge University, where he was a fellow of Robinson College.

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addressed, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of particular mental states. Aspects of the mind that are studied include mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and its neural correlates, the ontology of the mind, the nature of cognition and of thought, and the relationship of the mind to the body.

William G. Lycan is an American philosopher and professor emeritus at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he was formerly the William Rand Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor. Since 2011, Lycan is also distinguished visiting professor of philosophy at the University of Connecticut, where he continues to research, teach, and advise graduate students.

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that investigates principles of reality transcending those of any particular science. Cosmology and ontology are traditional branches of metaphysics. It is concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world. Someone who studies metaphysics can be called either a "metaphysician" or a "metaphysicist".

Theories of mental representation are those that rest the cognitive abilities of the mind on the processing of content-laden vehicles, called representations. Naturalizing these theories involves an account of how a representation, initially posited as a theoretical construct, can be realized in a physical system. A central aspect of any account of representation is how they derive and designate semantic content. The possession of meaningful content is the most characteristic property of representations and arguably integral to their functionality. The project of the naturalistic philosopher is to provide an account of the representation relationship between a representation A and its object of intentional content a, such that having content A is entailed by standing in a particular relation with a.

The first half of the topic of agency deals with the behavioral sense, or outward expressive evidence thereof. In behavioral psychology, agents are goal-directed entities that are able to monitor their environment to select and perform efficient means-ends actions that are available in a given situation to achieve an intended goal. Behavioral agency, therefore, implies the ability to perceive and to change the environment of the agent. Crucially, it also entails intentionality to represent the goal-state in the future, equifinal variability to be able to achieve the intended goal-state with different actions in different contexts, and rationality of actions in relation to their goal to produce the most efficient action available. Cognitive scientists and Behavioral psychologists have thoroughly investigated agency attribution in humans and non-human animals, since social cognitive mechanisms such as communication, social learning, imitation, or theory of mind presuppose the ability to identify agents and differentiate them from inanimate, non-agentive objects. This ability has also been assumed to have a major effect on inferential and predictive processes of the observers of agents, because agentive entities are expected to perform autonomous behavior based on their current and previous knowledge and intentions. On the other hand, inanimate objects are supposed to react to external physical forces.

References

- What Minds Can Do : Intentionality in a Non-Intentional World by Pierre Jacob 1997 Cambridge University Press. [On a graduate level covers the issues of the naturalization of intentionality from a weak intentional realist perspective while providing critical but fair to a fault and practically thorough articulation of the intentional irrealism's various positions particularly as based upon Quine's epistemological "double standard" between pragmatic usefulness of propositional attitudes in comparison with their "emptiness" and "baselessness" for a scientific determination of reality : this is epitomized in Dennett's "intentional stance" and "patternalism", etc. Chapters covering artificial intelligence, teleology, etc.]