Aquilegia is a genus of about 60–70 species of perennial plants that are found in meadows, woodlands, and at higher altitudes throughout the Northern Hemisphere, known for the spurred petals of their flowers.

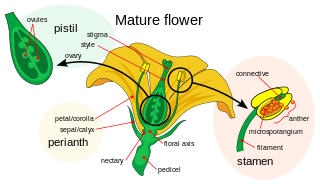

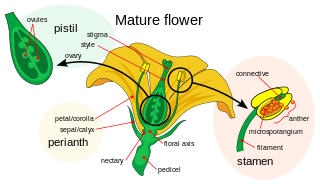

A pollinator is an animal that moves pollen from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma of a flower. This helps to bring about fertilization of the ovules in the flower by the male gametes from the pollen grains.

Petals are modified leaves that surround the reproductive parts of flowers. They are often brightly colored or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. All of the petals of a flower are collectively known as the corolla. Petals are usually accompanied by another set of modified leaves called sepals, that collectively form the calyx and lie just beneath the corolla. The calyx and the corolla together make up the perianth, the non-reproductive portion of a flower. When the petals and sepals of a flower are difficult to distinguish, they are collectively called tepals. Examples of plants in which the term tepal is appropriate include genera such as Aloe and Tulipa. Conversely, genera such as Rosa and Phaseolus have well-distinguished sepals and petals. When the undifferentiated tepals resemble petals, they are referred to as "petaloid", as in petaloid monocots, orders of monocots with brightly colored tepals. Since they include Liliales, an alternative name is lilioid monocots.

Iridaceae is a family of plants in order Asparagales, taking its name from the irises. It has a nearly global distribution, with 69 accepted genera with a total of c. 2500 species. It includes a number of economically important cultivated plants, such as species of Freesia, Gladiolus, and Crocus, as well as the crop saffron.

Aquilegia formosa, the crimson columbine, western columbine, or (ambiguously) "red columbine", is a common wildflower native to western North America, from Alaska to Baja California, and eastward to Montana and Wyoming.

Aquilegia coerulea, the Colorado blue columbine, is a species of flowering plant in the buttercup family Ranunculaceae, native to the Rocky Mountains, USA. Aquilegia coerulea is the state flower of Colorado.

Nectar is a sugar-rich liquid produced by plants in glands called nectaries or nectarines, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to animal mutualists, which in turn provide herbivore protection. Common nectar-consuming pollinators include mosquitoes, hoverflies, wasps, bees, butterflies and moths, hummingbirds, honeyeaters and bats. Nectar plays a crucial role in the foraging economics and evolution of nectar-eating species; for example, nectar foraging behavior is largely responsible for the divergent evolution of the African honey bee, A. m. scutellata and the western honey bee.

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants. Flowers produce gametophytes, which in flowering plants consist of a few haploid cells that produce gametes. The "male" gametophyte, which produces non-motile sperm, is enclosed within pollen grains; the "female" gametophyte is contained within the ovule. When pollen from the anther of a flower is deposited on the stigma, this is called pollination. Some flowers may self-pollinate, producing seed using pollen from the same flower or a different flower of the same plant, but others have mechanisms to prevent self-pollination and rely on cross-pollination, when pollen is transferred from the anther of one flower to the stigma of another flower on a different individual of the same species.

Ornithophily or bird pollination is the pollination of flowering plants by birds. This sometimes coevolutionary association is derived from insect pollination (entomophily) and is particularly well developed in some parts of the world, especially in the tropics, Southern Africa, and on some island chains. The association involves several distinctive plant adaptations forming a "pollination syndrome". The plants typically have colourful, often red, flowers with long tubular structures holding ample nectar and orientations of the stamen and stigma that ensure contact with the pollinator. Birds involved in ornithophily tend to be specialist nectarivores with brushy tongues and long bills, that are either capable of hovering flight or light enough to perch on the flower structures.

Pollination syndromes are suites of flower traits that have evolved in response to natural selection imposed by different pollen vectors, which can be abiotic or biotic, such as birds, bees, flies, and so forth through a process called pollinator-mediated selection. These traits include flower shape, size, colour, odour, reward type and amount, nectar composition, timing of flowering, etc. For example, tubular red flowers with copious nectar often attract birds; foul smelling flowers attract carrion flies or beetles, etc.

Hyles lineata, also known as the white-lined sphinx, is a moth of the family Sphingidae. They are sometimes known as the hummingbird moth because of their bird-like size and flight patterns.

Nectar robbing is a foraging behavior utilized by some organisms that feed on floral nectar, carried out by feeding from holes bitten in flowers, rather than by entering through the flowers' natural openings. "Nectar robbers" usually feed in this way, avoiding contact with the floral reproductive structures, and therefore do not facilitate plant reproduction via pollination. Because many species that act as pollinators also act as nectar robbers, nectar robbing is considered to be a form of exploitation of plant-pollinator mutualism. While there is variation in the dependency on nectar for robber species, most species rob facultatively.

Evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) is the study of developmental programs and patterns from an evolutionary perspective. It seeks to understand the various influences shaping the form and nature of life on the planet. Evo-devo arose as a separate branch of science rather recently. An early sign of this occurred in 1999.

Important structures in plant development are buds, shoots, roots, leaves, and flowers; plants produce these tissues and structures throughout their life from meristems located at the tips of organs, or between mature tissues. Thus, a living plant always has embryonic tissues. By contrast, an animal embryo will very early produce all of the body parts that it will ever have in its life. When the animal is born, it has all its body parts and from that point will only grow larger and more mature. However, both plants and animals pass through a phylotypic stage that evolved independently and that causes a developmental constraint limiting morphological diversification.

In evolutionary biology, a key innovation, also known as an adaptive breakthrough or key adaptation, is a novel phenotypic trait that allows subsequent radiation and success of a taxonomic group. Typically they bring new abilities that allows the taxa to rapidly diversify and invade niches that were not previously available. The phenomenon helps to explain how some taxa are much more diverse and have many more species than their sister taxa. The term was first used in 1949 by Alden H. Miller who defined it as "key adjustments in the morphological and physiological mechanism which are essential to the origin of new major groups", although a broader, contemporary definition holds that "a key innovation is an evolutionary change in individual traits that is causally linked to an increased diversification rate in the resulting clade".

Ecological speciation is a form of speciation arising from reproductive isolation that occurs due to an ecological factor that reduces or eliminates gene flow between two populations of a species. Ecological factors can include changes in the environmental conditions in which a species experiences, such as behavioral changes involving predation, predator avoidance, pollinator attraction, and foraging; as well as changes in mate choice due to sexual selection or communication systems. Ecologically-driven reproductive isolation under divergent natural selection leads to the formation of new species. This has been documented in many cases in nature and has been a major focus of research on speciation for the past few decades.

Floral scent, or flower scent, is composed of all the volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or aroma compounds, emitted by floral tissue. Other names for floral scent include, aroma, fragrance, floral odour or perfume. Flower scent of most flowering plant species encompasses a diversity of VOCs, sometimes up to several hundred different compounds. The primary functions of floral scent are to deter herbivores and especially folivorous insects, and to attract pollinators. Floral scent is one of the most important communication channels mediating plant-pollinator interactions, along with visual cues.

Pelorism is the term, said to be first used by Charles Darwin, for the formation of 'peloric flowers' which botanically is the abnormal production of radially symmetrical (actinomorphic) flowers in a species that usually produces bilaterally symmetrical (zygomorphic) flowers. These flowers are spontaneous floral symmetry mutants. The term epanody is also applied to this phenomenon. Bilaterally symmetrical (zygomorphic) flowers are known to have evolved several times from radially symmetrical (actinomorphic) flowers, these changes being linked to increasing specialisation in pollinators.

UV coloration is a natural phenomenon that leads to unique interactions between organisms that have evolved the ability to perceive these wavelengths of light. It serves as one method to attract pollinators to the flower along with scent, shape, and nectar quality. Flowers are known for their range of visible colors that humans can see with their eyes and observe an array of different shades and patterns. The naked eye cannot see the ultraviolet coloration many flowers employ to bring attention to themselves. By either reflecting or absorbing UV light waves, flowers are able to communicate with pollinators. This allows plants that may require an animal pollinator to stand out from other flowers or distinguish where their flowers are in a muddied background of other plant parts. For the plant, it is important to share and receive pollen so they can reproduce, maintain their ecological role, and guide the evolutionary history of the population.

Aquilegia sibirica, commonly known as the Siberian columbine, is a species of flowering plant in the genus Aquilegia native to the north-central Asian regions of Siberia, northern Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and Xinjiang. A hardy perennial plant, it prefers temperate environments. The Siberian columbine can be between one and two feet tall with flowers that are lilac-blue and white in color.