Ammonius Saccas was a Hellenistic Platonist self-taught philosopher from Alexandria, generally regarded as the precursor of Neoplatonism and/or one of its founders. He is mainly known as the teacher of Plotinus, whom he taught from 232 to 242. He was undoubtedly the most significant influence on Plotinus in his development of Neoplatonism, although little is known about his own philosophical views. Later Christian writers stated that Ammonius was a Christian, but it is now generally assumed that there was a different Ammonius of Alexandria who wrote biblical texts.

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the demiurge is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. The Gnostics adopted the term demiurge. Although a fashioner, the demiurge is not necessarily the same as the creator figure in the monotheistic sense, because the demiurge itself and the material from which the demiurge fashions the universe are both considered consequences of something else. Depending on the system, they may be considered either uncreated and eternal or the product of some other entity.

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite was a Greek author, Christian theologian and Neoplatonic philosopher of the late 5th to early 6th century, who wrote a set of works known as the Corpus Areopagiticum or Corpus Dionysiacum.

Proclus Lycius, called Proclus the Successor, was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers of late antiquity. He set forth one of the most elaborate and fully developed systems of Neoplatonism and, through later interpreters and translators, exerted an influence on Byzantine philosophy, Early Islamic philosophy, Scholastic philosophy, and German Idealism, especially G.W.F. Hegel, who called Proclus's Platonic Theology "the true turning point or transition from ancient to modern times, from ancient philosophy to Christianity."

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen, was Bishop of Nyssa in Cappadocia from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 395. He is venerated as a saint in Eastern Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Oriental Orthodoxy, Anglicanism, and Lutheranism. Gregory, his elder brother Basil of Caesarea, and their friend Gregory of Nazianzus are collectively known as the Cappadocian Fathers.

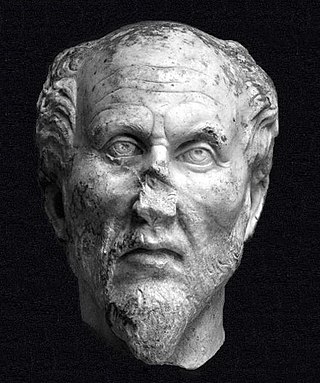

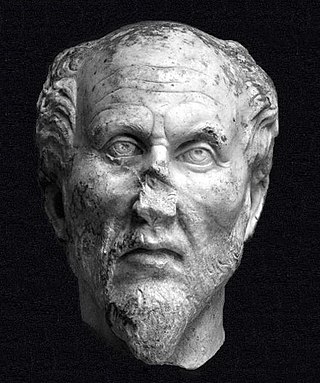

Plotinus was a Greek Platonist philosopher, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher was the self-taught philosopher Ammonius Saccas, who belonged to the Platonic tradition. Historians of the 19th century invented the term "neoplatonism" and applied it to refer to Plotinus and his philosophy, which was vastly influential during late antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. Much of the biographical information about Plotinus comes from Porphyry's preface to his edition of Plotinus' most notable literary work, The Enneads. In his metaphysical writings, Plotinus described three fundamental principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul. His works have inspired centuries of pagan, Jewish, Christian, Gnostic, and early Islamic metaphysicians and mystics, including developing precepts that influence mainstream theological concepts within religions, such as his work on duality of the One in two metaphysical states.

Theurgy, also known as divine magic, is one of two major branches of the magical arts, the other being practical magic or thaumaturgy. Theurgy describes the ritual practices associated with the invocation or evocation of the presence of one or more deities, especially with the goal of achieving henosis and perfecting oneself.

Apophatic theology, also known as negative theology, is a form of theological thinking and religious practice which attempts to approach God, the Divine, by negation, to speak only in terms of what may not be said about the perfect goodness that is God. It forms a pair together with cataphatic theology, which approaches God or the Divine by affirmations or positive statements about what God is.

Christian mysticism is the tradition of mystical practices and mystical theology within Christianity which "concerns the preparation [of the person] for, the consciousness of, and the effect of [...] a direct and transformative presence of God" or Divine love. Until the sixth century the practice of what is now called mysticism was referred to by the term contemplatio, c.q. theoria, from contemplatio, "looking at", "gazing at", "being aware of" God or the Divine. Christianity took up the use of both the Greek (theoria) and Latin terminology to describe various forms of prayer and the process of coming to know God.

Christianity and Hellenistic philosophies experienced complex interactions during the first to the fourth centuries.

Numenius of Apamea was a Greek philosopher, who lived in Rome, and flourished during the latter half of the 2nd century AD. He was a Neopythagorean and forerunner of the Neoplatonists.

Vladimir Nikolaievich Lossky was a Russian Eastern Orthodox theologian exiled in Paris. He emphasized theosis as the main principle of Eastern Orthodox Christianity.

Gnosticism refers to a collection of religious groups originating in Jewish religiosity in Alexandria in the first few centuries AD. Neoplatonism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that took shape in the 3rd century, based on the teachings of Plato and some of his early followers. While Gnosticism was influenced by Middle Platonism, neoplatonists from the third century onward rejected Gnosticism. Nevertheless, Alexander J. Mazur argues that many neoplatonic concepts and ideas are ultimately derived from Sethian Gnosticism during the third century in Lower Egypt, and that Plotinus himself may have been a Gnostic before nominally distancing himself from the movement.

Mystical theology is the branch of theology in the Christian tradition that deals with divine encounter and the self-communication of God with the faithful; such as to explain mystical practices and states, as induced by contemplative practices such as contemplative prayer, called theoria from the Greek for contemplation.

Henosis is the classical Greek word for mystical "oneness", "union" or "unity". In Neoplatonism, henosis is unification with what is fundamental in reality: the One, the Source, or Monad. The Neoplatonic concept has precedents in the Greek mystery religions as well as parallels in Eastern philosophy. It is further developed in the Corpus Hermeticum, in Christian theology, Islamic Mysticism, soteriology and mysticism, and is an important factor in the historical development of monotheism during Late Antiquity.

Emanation is a belief, found in Neoplatonism, that the cause of certain beings or states of being consists of an overflow from the essence of God or other higher spiritual beings, as opposed to a special act of creation. This overflow is usually conceived in a non-temporal way as a permanent relationship of causation rather than as an event causing an entity to come into existence at a given point in time. The word "emanation" can refer either to the process of emanation or to the thing emanated.

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common ideas it maintains is monism, the doctrine that all of reality can be derived from a single principle, "the One".

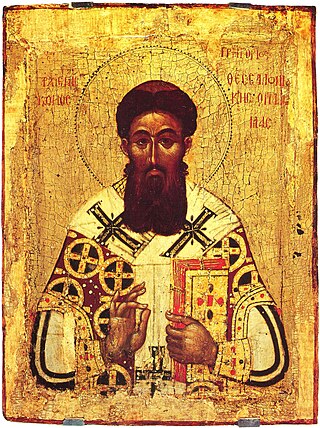

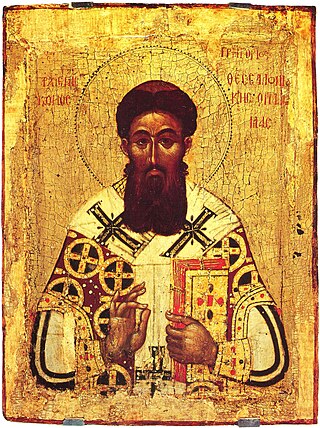

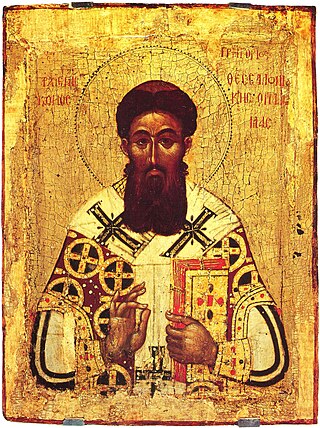

The Hesychast controversy was a theological dispute in the Byzantine Empire during the 14th century between supporters and opponents of Gregory Palamas. While not a primary driver of the Byzantine Civil War, it influenced and was influenced by the political forces in play during that war. The dispute concluded with the victory of the Palamists and the inclusion of Palamite doctrine as part of the dogma of the Eastern Orthodox Church as well as the canonization of Palamas.

20th century Eastern Orthodox theology has been dominated by neo-Palamism, the revival of St. Palamas and hesychasm. John Behr characterizes Eastern Orthodox theology as having been "reborn in the twentieth century." Norman Russell describes Eastern Orthodox theology as having been dominated by an "arid scholasticism" for several centuries after the fall of Constantinople. Russell describes the postwar re-engagement of modern Greek theologians with the Greek Fathers, which occurred with the help of diaspora theologians and Western patristic scholars. A significant component of this re-engagement with the Greek Fathers has been a rediscovery of Palamas by Greek theologians; Palamas had previously been given less attention than the other Fathers.

Okhêma refers to the "carrier" or "vehicle" of the soul, serving as the intermediary between the body and the soul, in Neoplatonism and the philosophical traditions it influenced.