The Trial of Socrates was held to determine the philosopher's guilt of two charges: asebeia (impiety) against the pantheon of Athens, and corruption of the youth of the city-state; the accusers cited two impious acts by Socrates: "failing to acknowledge the gods that the city acknowledges" and "introducing new deities".

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power is held by the ruler, known as an autocrat. It includes most forms of monarchy and dictatorship, while it is contrasted with democracy and feudalism. Various definitions of autocracy exist. They may restrict autocracy to cases where power is held by a single individual, or they may define autocracy in a way that includes a group of rulers who wield absolute power. The autocrat has total control over the exercise of civil liberties within the autocracy, choosing under what circumstances they may be exercised, if at all. Governments may also blend elements of autocracy and democracy, forming an anocracy. The concept of autocracy has been recognized in political philosophy since ancient times.

Year 403 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Tribunate of Mamercinus, Varus, Potitus, Iullus, Crassus and Fusus. The denomination 403 BC for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Thrasybulus was an Athenian general and democratic leader. In 411 BC, in the wake of an oligarchic coup at Athens, the pro-democracy sailors at Samos elected him as a general, making him a primary leader of the ultimately successful democratic resistance to the coup. As general, he was responsible for recalling the controversial nobleman Alcibiades from exile, and the two worked together extensively over the next several years. In 411 and 410, Thrasybulus was in command along with Alcibiades and others at several critical Athenian naval victories.

Theramenes was an Athenian military leader and statesman, prominent in the final decade of the Peloponnesian War. He was active during the two periods of oligarchic government at Athens, the 400 and later the Thirty Tyrants, as well as in the trial of the generals who had commanded at Arginusae in 406 BC. A moderate oligarch, he often found himself caught between the democrats on the one hand and the extremist oligarchs on the other. Successful in replacing a narrow oligarchy with a broader one in 411 BC, he failed to achieve the same end in 404 BC, and was executed by the extremists whose policies he had opposed.

In political science, a political system means the type of political organization that can be recognized, observed or otherwise declared by a state.

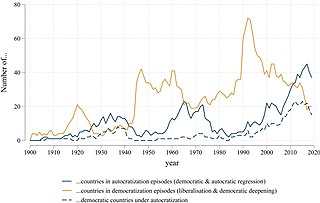

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.

The History of the Peloponnesian War is a historical account of the Peloponnesian War, which was fought between the Peloponnesian League and the Delian League. It was written by Thucydides, an Athenian historian who also served as an Athenian general during the war. His account of the conflict is widely considered to be a classic and regarded as one of the earliest scholarly works of history. The History is divided into eight books.

Proponents of democratic peace theory argue that both electoral and republican forms of democracy are hesitant to engage in armed conflict with other identified democracies. Different advocates of this theory suggest that several factors are responsible for motivating peace between democratic states. Individual theorists maintain "monadic" forms of this theory ; "dyadic" forms of this theory ; and "systemic" forms of this theory.

The iron law of oligarchy is a political theory first developed by the German-born Italian sociologist Robert Michels in his 1911 book Political Parties. It asserts that rule by an elite, or oligarchy, is inevitable as an "iron law" within any democratic organization as part of the "tactical and technical necessities" of the organization.

The term "illiberal democracy" describes a governing system that hides its "nondemocratic practices behind formally democratic institutions and procedures". There is a lack of consensus among experts about the exact definition of illiberal democracy or whether it even exists.

The Athenian coup of 411 BC was the result of a revolution that took place during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. The coup overthrew the democratic government of ancient Athens and replaced it with a short-lived oligarchy known as the Four Hundred.

Liberal democracy, western-style democracy, or substantive democracy is a form of government that combines the organization of a representative democracy with ideas of liberal political philosophy.

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years in Ancient Greece, marked by much of the eastern Aegean and northern regions of Greek culture gaining increased autonomy from the Persian Empire; the peak flourishing of democratic Athens; the First and Second Peloponnesian Wars; the Spartan and then Theban hegemonies; and the expansion of Macedonia under Philip II. Much of the early defining mathematics, science, artistic thought, theatre, literature, philosophy, and politics of Western civilization derives from this period of Greek history, which had a powerful influence on the later Roman Empire. Part of the broader era of classical antiquity, the classical Greek era ended after Philip II's unification of most of the Greek world against the common enemy of the Persian Empire, which was conquered within 13 years during the wars of Alexander the Great, Philip's son.

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of democracy, civil liberties, and political plurality. It involves the use of strong central power to preserve the political status quo, and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voting. Political scientists have created many typologies describing variations of authoritarian forms of government. Authoritarian regimes may be either autocratic or oligarchic and may be based upon the rule of a party or the military. States that have a blurred boundary between democracy and authoritarianism have some times been characterized as "hybrid democracies", "hybrid regimes" or "competitive authoritarian" states.

Anocracy, or semi-democracy, is a form of government that is loosely defined as part democracy and part dictatorship, or as a "regime that mixes democratic with autocratic features". Another definition classifies anocracy as "a regime that permits some means of participation through opposition group behavior but that has incomplete development of mechanisms to redress grievances." The term "semi-democratic" is reserved for stable regimes that combine democratic and authoritarian elements. Scholars distinguish anocracies from autocracies and democracies in their capability to maintain authority, political dynamics, and policy agendas. Similarly, the regimes have democratic institutions that allow for nominal amounts of competition. Such regimes are particularly susceptible to outbreaks of armed conflict and unexpected or adverse changes in leadership.

A hybrid regime is a type of political system often created as a result of an incomplete democratic transition from an authoritarian regime to a democratic one. Hybrid regimes are categorized as having a combination of autocratic features with democratic ones and can simultaneously hold political repressions and regular elections. Hybrid regimes are commonly found in developing countries with abundant natural resources such as petro-states. Although these regimes experience civil unrest, they may be relatively stable and tenacious for decades at a time. There has been a rise in hybrid regimes since the end of the Cold War.

Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century BC in the Greek city-state of Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. Although Athens is the most famous ancient Greek democratic city-state, it was not the only one, nor was it the first; multiple other city-states adopted similar democratic constitutions before Athens. By the late 4th century BC, as many as half of the over one thousand existing Greek cities might have been democracies. Athens practiced a political system of legislation and executive bills. Participation was open to adult, free male citizens The metics probably constituted no more than 30 percent of the total adult population.

The territorial peace theory finds that the stability of a country's borders has a large influence on the political climate of the country. Peace and stable borders foster a democratic and tolerant climate, while territorial conflicts with neighbor countries have far-reaching consequences for both individual-level attitudes, government policies, conflict escalation, arms races, and war.