Rohl's New Chronology

David Rohl's published works A Test of Time (1995), Legend (1998), The Lost Testament (2002), and The Lords of Avaris (2007) set forth Rohl's theories for re-dating the major civilisations of the ancient world. A Test of Time proposes a down-dating (bringing closer to the present), by several centuries, of the New Kingdom of Egypt, thus needing a major revision of the conventional chronology of ancient Egypt. Rohl asserts that this would let scholars identify some of the major events in the Hebrew Bible with events in the archaeological record and identify some of the well-known biblical characters with historical figures who appear in contemporary ancient texts. Lowering the Egyptian dates also dramatically affects the dating of dependent chronologies, such as that currently used for the Greek Heroic Age of the Late Bronze Age, removing the Greek Dark Ages, and lowering the dates of the Trojan War to within two generations of a ninth-century-BC Homer and his most famous composition, the Iliad .

The New Chronology lowers the Egyptian dates (established within the traditional chronology) by up to 350 years at points before the universally accepted fixed date of 664 BC for the sacking of Thebes by Ashurbanipal. For example, the New Chronology would redate the beginning of Egypt's 19th Dynasty from 1295 BC to 961 BC.

Before the 1995 publication of A Test of Time, Thomas L. Thompson, a theologian associated with Biblical Minimalism, had insisted that any attempt to write history based on a direct integration of biblical and extra-biblical sources was "not only dubious but wholly ludicrous". [4] Rohl explained his view on the issue in The Lost Testament (2007): "Is the Old Testament history or myth? The only way to answer that question is to investigate the biblical stories using the archaeological evidence, combined with a study of the ancient texts of the civilisations which had a role to play in the Bible story. But this has to be done with an open mind. In my view the biblical text – just like any other ancient document – should be treated as a potentially reliable historical source until it can be demonstrated to be otherwise." [5] Rohl had previously remarked in A Test of Time (1995) that he "did not originally set out to challenge our current understanding of the Old Testament narratives. This has come about simply because of the need to explore the ramifications of my TIP [Egyptian Third Intermediate Period] research. I have no religious axe to grind – I am simply an historian in search of some historical truth." [6]

Rohl's redating is based on criticism of three of the four arguments which he considers are the original foundations of the conventional chronology for the Egyptian New Kingdom:

- He asserts that the identification of "Shishaq [Shishak], King of Egypt" (1 Kings 14:25f; 2 Chronicles 12:2-9) with Shoshenq I, first proposed by Jean-François Champollion, is based on incorrect conclusions. Rohl argues instead that Shishaq should be identified with Ramesses II (probably pronounced Riamashisha), which would move the date of Ramesses' reign forward some 300 years.

- Rohl also asserts that the record in the Ebers Papyrus of the rising of Sirius in the ninth regnal year of Amenhotep I, which is used in conventional chronology to fix that year to either 1542 BC or 1517 BC, has been misread, and instead should be understood as evidence for a reform in the Egyptian calendar.

- Papyrus Leiden I.350, which dates to the 52nd year of Ramesses II, records a lunar observation which places that year of Ramesses's reign in one of 1278, 1253, 1228 or 1203 BC within the date-range of the conventional chronology. Having questioned the value of the Ebers Papyrus, Rohl argues that, since the lunar cycle repeats itself every 25 years, it is only useful for fine tuning a chronology and could equally apply to dates 300 years later as in the New Chronology.

Thus, Rohl is of the opinion that none of these three foundations of the conventional Egyptian chronology are secure, and that the sacking of Thebes by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 664 BC is the earliest fixed date in Egyptian history.

Evidence adduced

Rohl bases his revised chronology (the New Chronology) on his interpretation of numerous archeological finds and genealogical records from Egypt. For example:

- Rohl notes that no Apis bull burials are recorded in the Lesser Vaults of the Serapeum of Saqqara for the Twenty-first and early Twenty-second Dynasties. He also argues that the reburial sequence of the mummies of the New Kingdom pharaohs in the Royal Cache (TT 320) shows that these two dynasties were contemporary (thus explaining why there are too few Apis burials for the period). Rohl finds that in the royal burial ground at Tanis it appears that the tomb of Osorkon II of the 22nd Dynasty was built before that of Psusennes I of the 21st Dynasty; in Rohl's view this can only be explained if the two dynasties were contemporary.

- Rohl offers inscriptions that list three non-royal genealogies which, when one attributes 20 to 23 years to a generation, show, according to Rohl, that Ramesses II flourished in the 10th century BC as Rohl advocates. In the conventional chronology, all three genealogies would be missing seven generations. He also argues that there are no genealogies that confirm the conventional dates for Ramesses II in the 13th century BC.

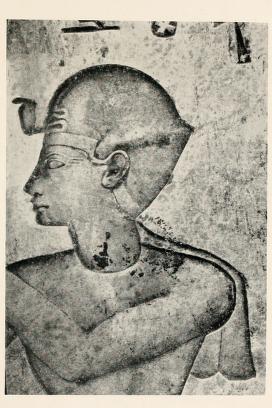

- One of Rohl's methods is the use of archaeoastronomy, which he employs to fix the date of a near-sunset solar eclipse during the reign of Akhenaten and observed from the city of Ugarit. Based on calculations, using computer astronomy programs, Rohl asserts that the only time when this eclipse could have occurred during the whole second millennium BC was on 9 May 1012 BC. This is approximately 350 years later than the conventional dates for Akhenaten (1353-1334 BC).

- Rohl's dates for Amenemhat III of the Twelfth Dynasty in the 17th century BC have found support in the work of astronomer David Lappin, whose research finds matches for a sequence of 37 out of 39 lunar month lengths recorded in 12th Dynasty contracts; the conventional chronology matches at best 21. According to Lappin, this pattern provides "startling" support for Rohl's chronology. [4]

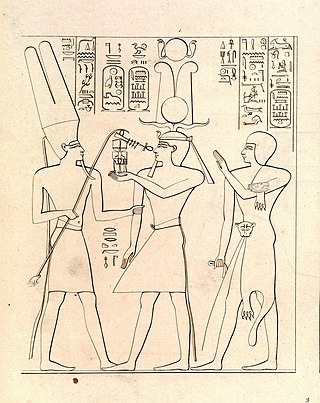

Shishaq

Most Egyptologists accept Shishaq as an alternative name for Shoshenq I. [7] [8] [9] Rohl disputes that Shoshenq's military activity fits the biblical account of Shishaq on the grounds that the two kings' campaigns are completely different and Jerusalem does not appear in the Shoshenq inscription as a subjected town. [10] He also points out that Ramesses did campaign against Israel and that he had a short form of his formal name which was in use in Palestine. [11] That name was Sysw, whilst the early Hebrew alphabet did not distinguish between S and SH, so the biblical name may have originally been Sysq. Rohl has also argued that the qoph ending may be a later misreading of the early sign for waw which in the 10th century was identical to the 7th century sign for qoph. Thus 7th-century Sysq may have been a mistaken later reading of 10th-century Sysw. [12]

The theory that Ramesses II (hypocoristicon Sysa), rather than Shoshenq I, should be identified with the biblical Shishak is not widely accepted. [13]

Kevin Wilson agrees only partially with David Rohl. Wilson accepts that there is a mismatch between the triumphal relief of Shoshenq I and the biblical description of King Shishak. However, he does not think that this discrepancy gives sufficient reason for doubting the identification of Shoshenq I with King Shishak of the Bible. Wilson writes about Shoshenq's inscription, "Contrary to previous studies, which have interpreted the relief as a celebration of his Palestine campaign, neither the triumphal relief nor any of its elements can be utilized as a source for historical data about that campaign. … the triumphal relief can unfortunately play no role in the reconstruction of Shoshenq’s campaign." [14] Wilson's view is not supported by Kenneth Kitchen who states: "That the great topographical list of Shoshenq I at Karnak is a document of the greatest possible value for the history and nature of his campaign against Judah and Israel is now clearly established beyond all dispute, thanks to the labours expended on that list by a series of scholars. However, the composition and interpretation of the list still require further examination and clarification". [15] Other leading scholars who have studied the campaign relief point out that it is indeed a unique list of subjected towns and not a copy of an earlier campaign by a more celebrated pharaoh. [16] [17] [18] [19] This originality makes it far more likely that it is a true representation of cities and locations brought under Egyptian control by the military activities of Shoshenq I.